One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer (3 page)

Read One to the Wolves, On the Trail of a Killer Online

Authors: Lois Duncan

When I finally got back to Albuquerque on a much later flight, Don and I were faced

with a decision that we had not expected to have to make for years. We knew that,

when my book was published, the charming Southwestern city where we had lived for

our whole married life would never be home to us again.

“We need to get out of here before the book comes out,” Don said. “There’s bound to

be retaliation.”

“From the Vietnamese?”

“That’s possible, of course, but we also could be in danger from the Hispanic suspects.

When the DA dropped charges against Miguel Garcia, he and his friends thought they

were off the hook. Now your book will come out, speculating that they possibly were

hired hit men. They won’t be happy about that.”

“The police are the ones I’m worried about,” I said.

Several of my former journalism students at the University of New Mexico were now

reporters for local newspapers and had told me disturbing stories about their experiences

with police harassment when they wrote articles that portrayed the department unfavorably.

Accusations of police brutality were becoming increasingly common in Albuquerque,

and the number of killings by police was reportedly far above the norm for a city

that size.

One highly publicized police shooting was engraved on my memory because it occurred

the same year Kait was shot. Peter Klunck, a small time drug dealer, had been chased

down and shot to death by police officers on the morning of the day Peter was scheduled

for a court appearance. Matt Griffin, the cop who fired the death shot, claimed self-defense,

although several witnesses, including a fellow officer, reported Peter was unarmed,

and Peter’s parents were convinced the killing was premeditated. The police department

rallied in defense of Griffin, who was kept on the force until July of that same year

when he killed a man who caught him hot-wiring a car. One week before Kait’s murder,

Matt Griffin was revealed to be the “Ninja Bandit,” a notorious bank robber. Despite

that revelation, police remained firm in their contention that Peter’s parents were

slanderous troublemakers who had no right to question Griffin’s motive for shooting

their son.

The longer Don and I discussed the possible ramifications of the book’s publication,

the more uneasy we became. After hashing it over, we decided not to take chances,

so Don applied for early retirement, and we bought a secondhand fifth-wheel trailer.

When the book was released, we planned to evacuate the town house and move into the

trailer at a campground outside the city limits.

But the book was not scheduled for publication until spring, which meant that, although

Don continued to put in his usual long hours at the office, my own life was on hold.

I was still under contract to write the last of three suspense novels, only two of

which had been completed at the time of Kait’s death, but I found it impossible to

create a fictional murder mystery when my mind would not focus on anything other than

our real one.

So, with nothing to do but kill time, I dutifully devoted my days to analyzing talk

shows. I had never before watched daytime television, and I found myself mesmerized

by the subject matter and the wildly contrasting participants. The guests on the

Joan Rivers Show

were a classy lot and obviously most had had media training.

The Maury Povitch Show

was not for the faint of heart, what with all the satanic cultists and serial killers,

but Maury had a nice smile. Oprah Winfrey and Phil Donahue ran opposite each, so I

took turns switching back and forth.

The Donahue Show

tended to intimidate me, as Phil’s guests were often so bizarre, and the studio audience

went straight for the jugular. The Oprah audience was kinder, perhaps as a reflection

of Oprah herself, who seemed like the sort of person who would be fun at a party.

I also developed warm feelings for Sally Jessy Raphael, who appeared sincerely sympathetic

to the parade of agonized bigamists, transvestites, and adult-children-of-dysfunctional-parents,

who trooped on and off the set to the cheers and applause of a surprisingly youthful

audience.

At the end of each “workday” of TV viewing, I would replay Bill’s training video and

compare my pathetic performance to those I had just witnessed. Every time, I found

new things to worry about. My voice was either too flat or too shrilly emotional;

I paused too long between sentences or jabbered so nervously that I ran out of breath;

I gestured too much or, conversely, clenched my hands together in my lap in a knot

of rigidity that made me appear catatonic. And, whenever I described the hours at

Kait’s bedside, holding her hand and waiting for her to die, I started to gasp as

if I had asthma.

Since Don’s last day of work was the tenth of December, we decided to take the trailer

on a maiden voyage to spend the holidays with our second daughter, Kerry, and her

family. In a campground in Texas it quickly became apparent why we had gotten such

a good deal on the trailer. It rained non-stop all Christmas week, and the roof sprung

so many leaks that we felt as if we were sleeping in a shower stall. On top of that,

our plumbing performed some sort of reflux action that sent floods of water gushing

out of the sink and toilet to join forces with the pools of rain

water. The ratty shag carpet soaked up the liquid like a blotter and emitted a pungent

odor of stale beer and cat urine that told us more about the former owners of the

trailer than we wanted to know.

Kerry tried to make our visit a festive one, but the going was rough for her. Both

our little granddaughters had ear infections, our son-in-law had just learned that

his job was being terminated, and Kerry herself was in her ninth month of pregnancy.

Despite our best efforts, we never quite got the holidays up and rolling. As the baby

of the family, Kait had been the pivot of Christmas, and memories of happier times

overwhelmed us.

“Remember when she wrapped up all her old toys and put them under the tree so she

would have more packages to open than Donnie?”

“Remember when she baked pies and forgot to put in sugar?”

“Remember when we took her to see

The Nutcracker

, and she brought the hamsters in her purse so they could see the Mouse King?”

I remember, I responded silently. Oh, yes, I remember.

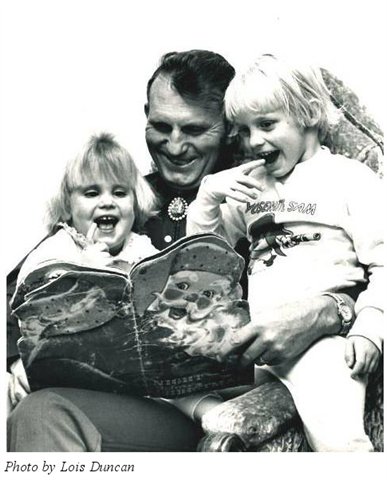

I remembered the chubby three-year-old, still damp from her bath, who snuggled on

Don’s lap as he read her

The Night Before Christmas

. I remembered the gregarious ten-year-old who sang Christmas carols off key as she

lined the driveway with luminarias. I remembered the starry-eyed teenager on the last

Christmas Eve of her life, filling a stocking for her boyfriend — “Dung says they

don’t have Christmas stockings in Vietnam. I’m going to sneak over and hang this on

his door knob.”

Precariously balanced on an emotional seesaw that could plunge me into depression

with the slightest bit of overload, I flipped over the edge on the day I made a last

minute dash to a department store to pick up a present that Kerry had placed on layaway.

As I stood waiting for the over-worked salesgirl to bring out the package, I heard

a girl’s voice call, “Mother!”

“Yes?” I responded automatically, and turned to see a pretty blond teenager pull a

blouse from a rack and hold it up in front of her.

“This is the one you ought to buy!” she announced emphatically to the middle-aged

woman standing next to her. “It’s in your colors!”

“Those are

your

colors!” the woman responded, laughing. “You only want me to buy that so you can borrow

it!”

Her daughter joined in the laughter. “Can’t blame me for trying! Oh, Mother, look—

isn’t that the coolest jacket!”

She grabbed the woman’s hand and dragged her across the aisle to another rack of clothing,

and a scene from the past came rushing back me.

It was the Mother’s Day that Kait was twelve, and she announced to me at breakfast

that she had a very special gift for me.

“I’ve neglected you lately,” she said solemnly. “I’ve been so busy that I haven’t

scheduled enough time for you. To make up for that, I’m going to spend the whole day

with you.” She smiled at my look of bewilderment. “

That’s

your present, Mother! I’m going to spend every minute of this entire day with you.

What shall we do first?”

“That sounds wonderful, honey,” I responded in amusement, “but I’m afraid I have work

to do.” I was running behind on an article assignment and had expected to devote the

day to getting it finished.

“That’s all right,” Kait said agreeably. “I’ll entertain you while you write. Then

we can go out to lunch and to a movie and then we can go someplace expensive to shop

for a blouse or something. You’re much too old to buy all your clothes at Wal-Mart.”

The idea of trying to write with a chattering parakeet perched next to me was inconceivable,

so I reluctantly put my assignment on hold and went out to “do the town” with Kait.

We had lunch at the Chic-Fil-A (Kait’s favorite eatery); saw a movie with Nicholas

Cage (Kait’s favorite actor); and ended up buying me a blouse (in Kait’s favorite

colors). Since Kait had forgotten to bring money, I picked up the tab.

“Did you like your present?” she chirped as we walked hand-in-hand to the parking

lot. “Wasn’t it special to get to spend so much time with me?”

“It certainly was,” I told her, trying not to dwell upon the fact that I would have

to work half the night to finish the article.

Oh, dear God, if only I could have that day back again! The sense of loss that struck

me was so intense that I thought for a moment I might die of it. Where was that orange

and yellow blouse today? Hanging at the back of my closet at the town house? On a

rack at the Goodwill Thrift Store? Or was it nothing but a sun-bleached rag on a shelf

in a corner of the laundry room of the home we had vacated? Why hadn’t I cherished

it, slept with it under my pillow or, at the very least, worn it to the funeral?

Did you like your present?

“It was a wonderful present,” I whispered now. “It was the most wonderful present

in the world — the chance to spend a whole day with you.”

On New Year’s Day the inevitable finally happened and my body followed the path of

my careening emotions. I was standing in Kerry’s kitchen, leaning over to take a

pan of chicken out of the oven, when I discovered that my left hand wouldn’t close

around the door handle. Then my left arm went limp. I tried to call out to the family,

who were already gathered at the dinner table, but the words came out in a garble.

What I was trying to say was, “I think I’ve had a stroke!”

On the way to the hospital I got my speech back and dictated a living will.

Later that night I became able to move my arm and hand. As I lay in the hospital bed,

clenching and re-clenching my left fist in a frenzied effort to reassure myself that

I could still do so, a nurse kept popping in to ask if I could swallow. I quickly

realized that swallowing was some kind of test so, of course, my mouth dried up every

time the nurse appeared. In between her visits I manufactured saliva, which I surreptitiously

stockpiled in the crevices of my mouth so that when she next materialized I could

demonstrate my swallowing skills.

“Do you understand that you’ve had a stroke?” she asked me.

I assured her that I did.

“So what is your emotional state?” she continued, consulting her checklist. “You have

four choices — denial, fear, anger, and acceptance.”

“Acceptance,” I said.

She raised her eyes from the list and regarded me suspiciously.

“You haven’t had time enough for acceptance.”

“Anger?” I suggested, although I didn’t feel angry. There was nothing and no one to

be angry with except Fate, and I knew for a fact that Fate dealt harsher blows than

this one.

The nurse looked relieved and checked the square beside “anger.”

The shock of seeing me babbling and drooling in her kitchen had driven Kerry into

labor and, while I was getting my brain scanned, she gave birth two floors below me.

I emerged from the MRI tube to find Don waiting with a wheelchair to take me down

to meet our first grandson, Ryan Duncan.

I remained in the hospital four days and had a myriad of tests which revealed no overt

cause for a stroke. I was in seemingly good health.