One Was Stubbron (3 page)

“You mean you refuse?”

“I guess that's what I mean.”

“You are a very stubborn man.”

“I believe what I want to believe. I believe this is a world. And anybody that tries to tell me that this glass and bottle are not real is going to get an awful argument from me.”

“Then,” said George Smiley, the Messiah, “my hand is forced. I sent no minions. I came myself. You are the last man. I and the rest of the Universe shall cease to believe in your soul and you shall cease to exist. Good day.”

“Good day,” I said.

He looked back once from the door. I was trying to pour myself a drink but the bottle neck chattered against the glass and the Old Space Ranger spilled. I felt his eyes.

And then there weren't a bottle and a glass in my hands!

I held nothing!

“Good day,” he said again in a cheerful voice. He was gone.

D

uring the remainder of that day I did nothing more than sit and look at the patterns in the fluffoplex floor. I was half angry, half scared, and I was trying my best to understand just what George Smiley, the Messiah, was doing. I have been told that I have a suspicious nature. However that may be, I suspected George Smiley. Every person I had seen for weeks, now that I came to think about it, had had that same strange fixity of expression which my wife had borne; just as though everyone had become a saint.

It was much against my principles to surrender to the extent of examining the problem but, at last, when nightâas I thoughtâhad come, I went into the next room and fumbled around until I found what papers my wife had accumulated during the past month or two. I sat and read, then, for nearly two hours.

But at the end of that time I was not even close to a solution. All I discovered was that George Smiley had come from Arcton with a message. Of course, I knew that everyone in the Universe was bored and would welcome any kind of diversion and that such a time, according to my Tribbon's

Rise and Fall of the American Empire,

provided unscrupulous men with a host of willing dupes for religious experimentation. That many of these had been maniacs was a fact which Tribbon, the great unbeliever, italicized. But, so far in history, no one man had managed to swing a nation, much less the Universe, around to his method of thinking. But it had been so long since any man had had to develop an original idea that almost any idea would have been acceptable. I suppose that it was the perfection of communication which made it possible for George Smiley to reach everyone everywhere. And the freedom which the Machine Magistration gave all religious exponents accounted for George Smiley's not being stopped.

And, worse luck, it seemed that I was the only man left that didn't want to slip off into the limbo.

It had already been proved that mass concentration could do away with material objects but that fact was so old that, until now, it had lain dormant except in the pranks of schoolboys who, learning about it for the first time, vanished desks out from in front of their professors.

George Smiley, according to these reports, was a virile fellow who had lived alone for years and years as a prospector on Arcton. But the fact that his parents were not known made me believe that perhaps both his father and his mother had finished this life as members of the famous Arcton Prison to which so many universal criminals were shipped. Did this George Smiley have a grudge against the whole Universe?

That sardonic smile of his and those terrifying eyesâ

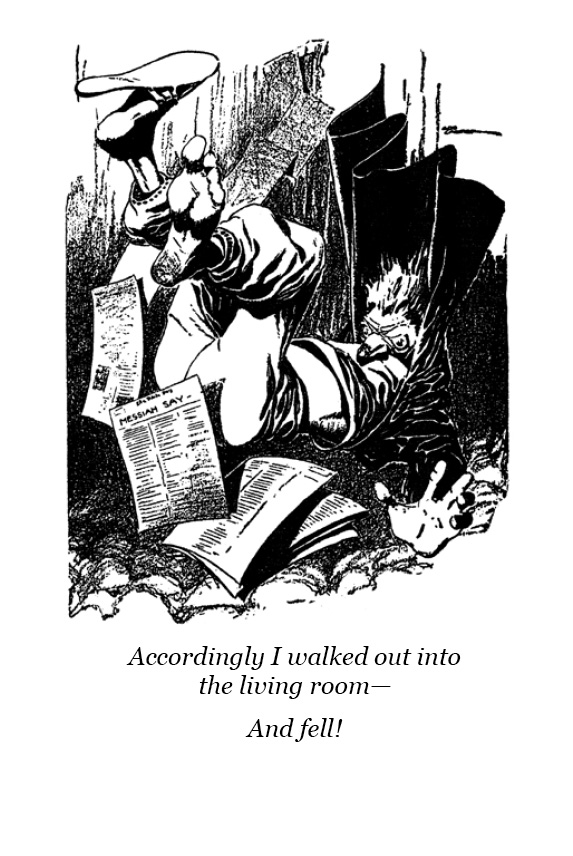

Well! It wasn't going to do me any good to sit and moon over the papers. Besides I felt I had better put them back before my wife found that I was reading them. Such surrender was unthinkable. Accordingly I walked out into the living roomâ

And fell!

There must be ground under me!

I lit!

And then I sat there, staring all about me in helpless bewilderment.

There wasn't any living room anymore. Maybe ⦠maybe my own roomâ

No, there was no sign of that either.

The papers! The papers I had been holding in my handâ

For a second one sheet rustled and then it, too, faded away.

There was something solid under me but that was all the solidity anywhere.

The city, perhaps the world, perhaps everything, was a flood of gray and curling mist! I felt of myself and was relieved to know that I was still myself anyway. For an instant I had wondered and, wondering, had felt myself thin and pale. But I was again solid and that upon which I was seated was still ground and so I took slight heart.

What, I wondered, had happened to my wife? And what had happened to the house? And the city? Certainly there must be something left of the city. And I began to feel that if I couldn't find something of it I should certainly go mad.

No more condensochow. No more Old Space Ranger. Oh, my goodness, yes, I had to find the city.

I stood up and groped before me, my hands nearly invisible in the murk. Step by step I found ground and, once, I thought I saw the corner of a building but, when I approached it closely, it, too, was gone.

F

or what seemed an hour I floundered about without being able to locate a street. I was getting angry, probably because I was getting scared. I consulted my watch and found out that it was half past ten. For what seemed a long while I kept on working along, expecting any moment to find a wall or a conveyer belt or a parked autoairbile but each next moment being disappointed. Finally I again looked at my watch; it was still half past ten. I thought that I must have missed the hands the first time in the absence of light but there was no missing them now, for the dial glowed softly and the mist itself seemed to have some quality of illumination. And then, having groped for what seemed yet a third half-hour, I looked once more at my watch. It was still half past ten!

Had something happened to Time?

Was I adrift in something which wasn't Space?

There were no quizclickers gaping for their pennies and their questions on each lamppost anymore, and so I had to try and answer it myself.

Yes, there was Space. I could feel myself and I knew I moved and so there must be Space. If it took me time to moveâ Perhaps, I thought, I had better locate someone else before I went completely mad.

For all this murk was seeping into my heart; like drifting smoke it curled and wound and spired, leaving black alleys stretching endlessly out and then rolling in upon the openings and swallowing them, leaving towers which stretched an infinity up and down and then devouring the towers. The very solidity on which I trod was hidden. There was no direction to anything and I felt that I might well be upside down or horizontal for all I knew. And I might not be walking on anything at allâ

And at that thought I began to fall. And falling, I feared earth. And fearing earth, I landed. I was ill. The thought that I must keep earth in mind or fall again was enough to make me do just that. And when again I was upon solidity I understood that I might drop an infinity, step by step, and never arrive at anything.

With great suddenness it came to me that so long as I believed in myself, I was. So long as I believed, there was Space. I was adrift in a murky ocean of mist, drowned in an immensity of nothingness, marooned in nonexistence.

I must find somebody.

I could not tolerate being alone.

And so I stumbled forward, groping hopefully. I was not used to walking any more than anyone else had been used to it. And I began to tire. I had fallen far, I knew and, I supposed, I would have to rise again to the same altitude of the city's site before I could discover anything.

But I was wrong. I had begun to wish violently for a bucket to bear me upward and then, banging my shins, I ran into the bucket. I had been wandering so long and so far without any contacts that I gripped that bucket as one grips a lost friend found again. Joyously I put my feet upon it. Gratefully I sank into its fluffoplex arms. And upward I went.

I was almost certain now that I had sunk no lower than the fifth level subsurface, for there the buckets began, and so I waited patiently for the conveyance to gently alight me upon a higher level. But I just kept on going up. Ordinarily it used to take a bucket not more than a minute to lift anyone twenty levels. But I realized that I had been sitting there at least five minutes, ascending swiftly through impenetrable mist.

In sudden panic I wondered where I was going. No bucket I had ever seen could have gone as high as this. Why ⦠why, I must be on a level with the Court Domes. OrâGod help me, I must be about to crash through the Weather Roof!

Suddenly I beheld a glass pane above. The bucket hit it squarely and rebounded. Madly I gripped at the chair arms. What if this bucket should vanish? What if the bucket, too, should cease to be? And it did.

I fell through the giddy mists. Only an aircab could have saved me. And then I wasn't falling. I was sitting in an aircab.

For several seconds I just sat there, clinging thankfully to the seat, not thinking at all about where I might be going. The driver must have seen me falling and zipped under me and was waiting now for me to recover my breath before he asked my destination. I leaned past the meter.

“Thank you,” I said. “If you'll take me to the Food Central, I'll be very grateful.”

A face ⦠a face and nothing more glowed briefly above the bar control and a voice snarled, “You can't do this to me. Who the hell do you think you are?” And the face was gone and the aircab went purring along, utterly driverless.

I was shaken, for it took me some time to understand just what was happening to me. I felt that if I went on like this much longer without the solace of a drink, I should perish. Oh, for a little snort of Old Space Ranger!

I drank it off and instantly felt better.

And then I felt worse.

I hadn't been carrying a glass of Old Space Ranger around with me all this time! And there wasn't anyone about who could have placed it in my hand!

And yet I had just had a drink!

And instead of being in that aircab I was sitting on nothing!

What had happened to the aircab? Certainly I still must be in it!

And there I was, purring along in the aircab again.

“Driver,” I said, “I don't understandâ”

“Don't try it on me!” snarled a face beside the meter. It vanished, all but the eyes, and these were so malevolent that I looked away.

The aircab vanished, too.

I sat very still on whatever this solidity was and tried to get myself straightened out. I had spoken to that driver twice and each time he had almost appeared. And I felt that the next time I tried to bring him out he would certainly deal roughly with me after the way of

hackies

. Each time I had imagined things it seemed that those things had come to pass.

Was I, then, a figment of my own imagination?

Shiver the thought!

Could I bring anything I wanted into being with my own thought? In his

Rise and Fall of the American Empire,

Tribbon hinted at the future possibility that the world and even the Universe might be destroyed by combined thought, the world and the Universe evidently being nothing but an idea. Had humanity committed mass suicide or mass combination to the exclusion of matter? And was I, then, the only one left whose belief in his own individuality was so great that that individuality still existed? And being the only individual mind still possessed by a man, could I create at will?

Or was I doomed for ever and ever to drift aimlessly through this clammy mist, timeless and alone?

I could not bear the thought. Tribbon had stated that man's one redeeming feature was his own ability to create, and that he, therefore, assigned creativeness to God. And Tribbon had said that when man no longer created, then man would no longer be. I had been the last manual farmer. Was I then the last man with ability to create?

Certainly if anything could be saved or if anything could exist, then it must be created by myself.

That was it!

I must create!

I

glowed with the idea. I walked around on my created solidity and laughed aloud. Always before I had had to callous my hands and besweat my brow, but now I only had to think. And what things wouldn't I create! I came as close to dancing as I ever did in all my life.

The mist!

I would create sunlight!

With all my wit I concentrated, and then! Then a shaft of light came from somewhere and played its beam upon me and warmed my rheumatic bones.

Sunlight!

By my own imagination I could bring to being light and warmth and cheer! I sang out, so great was my joy.

Now let me create a meadow. A meadow which I would surround with trees and cross with a brook. I closed my eyes and concentrated and, when I opened them again, there was the meadow!

I started to caper out into the tall grass and then, midpace, stopped dead still. What had happened to the sunlight? The mist so befogged this meadow that it could scarcely be seen. Sunlight!