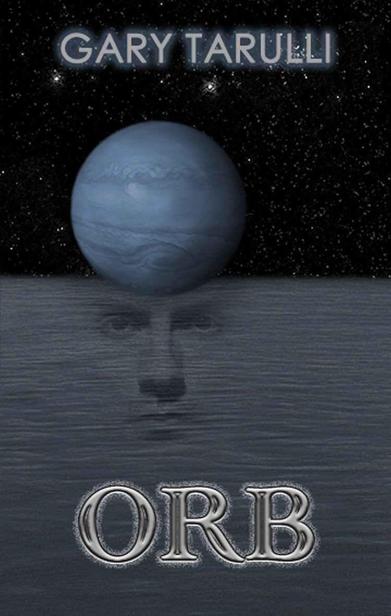

Orb

Authors: Gary Tarulli

Tags: #Adventure, #Science Fiction, #sci-fi, #Outer space, #Space, #water world, #Gary Tarulli, #Orb, #outer space adventure

R B

Gary Tarulli

Copyright © 2011 by Gary Tarulli

All rights reserved

First Edition

Cover illustration by Phil Young

youngfx.squarespace.com

eBook edition by eBooks by Barb for

booknook.biz

Thanks, Doc

I WAS ATTEMPTING to escape the confines of the box I found myself in, the one I had spent the last forty-one years creating.

Watching Earth disappear from view, I wondered if I was taking my concept of self-improvement a bit too far.

My name is Kyle Lorenzo. On 10 August 2232, I found myself onboard the research vessel

Desio

heading outbound on an eight-hundred-trillion kilometer to a planet some galactic cartographer devoid of imagination designated as 231-P5.

In due course you will learn much about me, but you have been sufficiently forewarned: I am a writer. You know this because there were individuals in the scientific community who openly objected to my joining Desio’s crew. Their accusation: I lacked a doctoral degree in any of the hard sciences which had served as the principal criterion for filling the complement of an exploratory mission. For this grievous offense I was tried in that ubiquitous and fickle court of public opinion known as the Cloud and summarily found guilty. The verdict, bereft the weight of law, enabled all sides to prevail: I managed to slip the bonds of Earth—only to be placed in solitarily confinement, with crew, onboard ship.

In my defense, the decision to recruit someone other than a scientist or physician for an extrasolar expedition was long overdue. I just never believed that person would be me. Or any writer, the profession having been assailed—marginalized—by two-hundred-fifty-odd years of facile communication and virtual entertainment choices. Reading, regarded as too demanding on one’s valuable time and energy, has fallen out of favor; the quaint phrase “I can read you like a book” morphing to mean “not at all.” Commensurate with the precipitous decline in reading there has been a decline in writing. Can a writer subsist without a sympathetic audience?

A few persist. Fewer can afford the insurance, a “malpractice” policy indemnifying against charges of plagiarism that have become commonplace ever since an army of copyright lawyers began accessing the Cloud AI to cross-match that brave new novel with all that was ever written. The lawyers inform us that there’s nothing new under the Sun. I hope to avoid the problem.

Where I’m heading there is a different sun.

They tell me it’s blue.

Those inclined to mathematics may chose to characterize my recruitment in terms of numbers. Or, to be more precise, percentages. Sixty percent of qualified applicants, counseled on the physical and psychological demands of prolonged spaceflight, had the good sense to drop out. (I refused to be dissuaded.) Of the remainder, seventy percent were eliminated by an exhausting series of physical fitness tests. (I keep fit, thanks to swimming and other water-related activities.) A merciless battery of mental health/aptitude tests subtracted another eighty percent. (Weeks later, Bruce Thompson, the mission leader, claimed that if the psych scores had not been graded on a curve there would have been nobody, especially me, left to choose from.)

A host of other screening criteria were applied, some I’ll never know, nor the reason why the Crew Selection Committee was so intent on a writer joining the expedition. Whatever the underlying motive, when you do the math, five hundred applicants were distilled down to a select dozen.

Who proceeded to effectively eliminate themselves.

Two candidates, claiming bragging rights for making such an elite group, their egos inflated to the size of the destination planet, unexpectedly bowed out. I subsequently discovered they intended to co-author an account of their “ordeal.”

One candidate excused herself after coming to the realization that she could not endure the emotional traumas of being separated from family and friends. Conversely, there was one writer who was

deliberately

trying to evade people intruding his life. (A few hundred trillion kilometers and a wormhole work exceptionally well). He learned firsthand the meaning of cruel irony when his one-man protest against lack of government funding for the arts, together with any chance of recruitment, ended upon detention for income tax evasion.

Yet another hopeful said she had come to her senses and “no longer found romance in squandering seven months of life cooped up in a tin can hurtling through the abyss while being forced to consume recycled human waste products.” Or overworked verbiage to such edifying effect.

These eleventh hour defections (

twenty-third hour

, military time compels me to say) put me in serious contention, but it was an odd stroke of good fortune that came into play: The person selected ahead of me, awarded a government grant to study the effects of electronic media on the arts, removed himself from consideration at the last possible moment.

And so here I am, onboard a star-class vessel, assigned the responsibility of creating, “as accurately as is humanly possible, a written record of the significant events of what will certainly be a great and historic scientific voyage.”

As best I can recall, that was the Central Space Agency’s (CSA) attempt at visionary words. They elicited this response from me: “Accuracy requires total objectivity, an impossibility when inevitably the observations a person makes are selectively filtered through the senses before entering the brain, whereupon they suffer repeated collisions, lose momentum, only to emerge in some altered form, at some later date, with some ulterior motive.” With this qualifying statement (which somehow didn’t impede my appointment) I informed the CSA that I would gladly do my very best. I’d make every attempt to be as honest and, using their word, accurate as humanly possible.

I then proceeded to press my luck by adding one more caveat:

Humanly

(again, their word) may not suffice either, if, as was fervently hoped for, the expedition encounters an advanced alien life-form.

And because I am the first filter evaluating what is to follow (you being the second), a brief, but necessary, word about this “box” I created for myself and the reason I was trying to climb out.

One facet of the damn thing may be painfully obvious: I was having a tough time earning a living. I like to believe it’s because anything longer than two-thousand words is a tough sell. Perhaps the expedition to 231-P5, anticipated for the last two years by most of Earth’s population, would provide some desperately needed name recognition, a rocket boost to my flagging career. It might even provide a wellspring of inspiration.

Here’s another facet: I characterize myself as borderline antisocial. In practice this means I have a tendency to keep to myself and (with one notable exception which I will soon make apparent) rarely enter into permanent relationships. I’ll have little choice but to address that personality quirk as I spend “seven months hurtling through the abyss cooped up in a tin can” along with the crew of

Desio

.

So I begin my exposition, but with a final word of caution: I am not a scientist. I will not be providing much in the way of scientific detail for what transpires. For such information I strongly encourage you to peruse the ship’s extensive logs, compiled by the five other crew members: four scientists and a medical doctor, each one preeminently qualified in their respective fields.

Good luck reading

their

accounts.

Although a significant chunk of my life was to be spent on the

Desio

, yet I had no knowledge of the illustrious person lending her a name. I assumed she had not been named after someone presently living. That practice had repeatedly proven itself as far too risky, human behavior being prone to failings that, when examined in the bright light of day, often result in a positive reputation being subjected to negative revision. This vexing problem is somewhat less applicable to the dead, although even the character of the deceased can be assaulted by the exhumation of damning personal revelations or reevaluated to suit the sensibilities of the time. To this last point, I’d not be too surprised if Vlad the Impaler had or will have an edifice of some import named after him.

But what of Desio? With a minimum of research, I uncovered a full name and bio.

Ardito Desio. Born in 1897. Died 2001. Explorer, geographer, and geologist. Leader of more than twenty scientific expeditions to isolated and geologically diverse areas of the globe; organizer of the first team to reach the summit of K-2 after five prior attempts by others had failed; author of seven hundred scientific papers—in sum, an adventurer who consumed eighty of his one hundred and four years traversing Earth during that period of time when remote and mysterious lands awaited discovery. A remarkable individual who, along with his name, had been relegated to the back shelf of history with the passage of time.

He was long gone but apparently not completely forgotten. Somebody bestowed his good name upon our ship. I made a point of finding out who. The appellation was selected, as is presently customary, by the ship’s commander, the aforementioned Bruce Thompson. The choice told me a little about Thompson. I would soon be finding out a whole lot more.

As for the

Desio

herself, form followed function: She was a sturdy, compact, and highly automated ship. I made her acquaintance during intensive training sessions when, along with the other members of his crew, Thompson instructed us in the function of everything from a recycling toilet to a gravity compensator. By teaching us himself, he would never have to hear bitching,

would he

, that we were not adequately instructed.

The personal touch and thoroughness of our training was atypical. Each member of a starship crew is normally designated responsibility for only two specialized assignments. Thompson insisted this was pure nonsense; we were sufficiently intelligent (and don’t let the remark go to your heads) to have a working knowledge of nearly all of

Desio’s

systems. His first objective was to rotate the crew through the tasks necessary for keeping his ship running at peak efficiency. Secondarily, he firmly believed that the challenge of acquiring and utilizing multiple skills would help reduce boredom. If you needed a third reason, it was because he said so. During training I came to know and respect Thompson. For one thing, he definitely knew his ship. There was no question about her he could not answer. For another, I have a particular appreciation for his brand of sarcasm.

The intricacies of some of the ship’s automated systems—propulsion, guidance, waste treatment, artificial gravity—I did not completely comprehend, nor was I required to. I did, however, learn enough to be amazed by their elegant and imaginative design, which approached an art form. I also came to appreciate just how dedicated mission engineers were to assuring the crew’s physical

and

psychological well-being.

One example was

Desio’s

optimized artificial gravity, set at 1.03E, where E=Earth. I asked the ship’s physician, Kelly Takara, about this. She explained that P5s gravity was only 0.93E, meaning an individual weighing 75 kilograms onboard would instantly “lose” 7.5 kilograms once on the planet, thereby mitigating the deleterious effects of physical inactivity during the prolonged voyage. Nine days of exploratory work would be conducted with greater comfort and, more important to mission planners, with greater efficiency.