Original Cyn (31 page)

Everybody pretended not to have heard the remark and soon all the guests were dabbing their eyes with handkerchiefs. Cyn couldn’t work out if the universal waterworks had been brought on by watching Flick and Jonny gazing into one another’s eyes as they recited alternate verses of “Take My Breath Away”—their magnificently tacky choice of wedding vows—or the kimchee fumes.

After the ceremony Joe was collared by Grandma Faye, who introduced him to Uncle Lou with the colostomy bag, who in turn started to bang on in a voice that the whole of Edgware could hear about the difference in symptoms between diverticulitis and colitis. Cyn was about to go and rescue him when she saw Hugh—mercifully still mumps-free—striding out toward her. His hand was pressed against his headset earpiece and he seemed deep in concentration. “Sorry, gorgeous, can’t stop,” he said briskly. “Laurent needs some help deciding if the cherries should be poured over the deep-fried ice cream or served separately.” Having just said he couldn’t stop, he then did just that. “Good God, so it’s you. Look, don’t take this the wrong way, but there is something distinctly niffy about you.”

“You’ve always known how to charm a girl.” Cyn smiled. She told the kimchee story again, but he was in such a flap over the deep-fried ice cream, he was only half listening. “So,” she said, “how are the rewrites going?”

“Hard work, but I’m coping. But what’s been fantastic is that Atahualpa and I have decided to move in together. We’re starting off in his flat, but it’s tiny, so we’ve already started looking for something bigger.”

“Oh, Huge. That’s fantastic news.”

“But what about you and Joe? I couldn’t be more glad that you two finally got together. He’s a great bloke. I knew you had him wrong.” She wanted to tell him they were getting married, but she felt it wouldn’t be right as her parents didn’t know.

They both looked up to see Joe standing next to them. “I knew she had me wrong, too,” he said to Hugh. “But I had a bugger of a job convincing her.”

Hugh smiled and nodded. “Look, I just wanted to say how much I appreciate you giving my screenplay to Ted Wiener. It’s not much, but I’d like to take the two of you out for dinner next week to say thank you.”

Cyn and Joe said that would be great. Suddenly Hugh was pressing his earpiece again. “I’ll phone you. Look, I have to dash. The Lima Dreamers have arrived and I need to show them where to set up.”

He jogged off. “I was about to come and rescue you from my mother and grandmother,” Cyn said to Joe.

“I didn’t remotely need rescuing. They’re great fun.” A waitress came up to them carrying a tray of champagne. Joe took two glasses and handed one to Cyn. “Your grandmother’s just been pitching me a film idea. Did you know her father escaped from Poland in a milk cart?”

“Oh, God, she’s not telling that story again. I hope you reminded her they already made

Fiddler on the Roof

.”

“I didn’t have to. Your mother made the point rather forcibly. I have to say, they’re a bit of a double act, those two.”

Cyn gave a short laugh. “So, did they tell you about the kimchee?”

He said they did.

“I thought the dress was bad enough. Now I stink as well.”

“Of course you don’t stink. There’s a faint trace of something, a slight aroma maybe, but the worst has gone.”

“Promise?”

“You have my word.” He gave her a kiss and a squeeze to make his point, almost making her spill her champagne. “And for the record, I love the dress. I’m a big Vivien Leigh fan.”

“You are such a charmer, do you know that?”

“I’m telling the truth,” he protested.

“Yeah, right.”

Everybody agreed that Laurent’s food was glorious. His fish balls, in particular, were a triumph. Even Uncle Lou with the colostomy bag tucked into a huge plate of chicken and peanut sauce. Everybody oohed and aahed over the chocolate fountain and deep-fried ice cream—which in the end was served covered with cherries. While the guests ate, the Lima Dreamers played easy-listening pop classics with an Incan twist.

Jonny made a speech thanking Flick for loving him and thanking Mal and Barbara for having him. Flick stood up and declared that this was the happiest day of her life, and then she presented Barbara, Bunty and Grandma Faye with huge bunches of flowers. Jonny’s best man, another solicitor, made a supposedly hilarious speech that consisted of several ponderous references to Jonny fulfilling his contractual obligations later that night. Mal said how much today reminded him of his wedding to Barbara.

“I can’t believe we’ve been married for nearly forty years.”

“I can,” Barbara heckled, which got a huge laugh.

He said the secret of a happy marriage was to make sure you didn’t go to bed angry. “You have to stay up until the problem is resolved. Last year Barbara and I didn’t get to sleep until March.”

As the laughter died down he began reminiscing about Jonny and Cyn when they were babies. “It seems like yesterday we were celebrating Jonny’s circumcision. It was then that we realized he had his mother’s balls.” Finally he turned to Flick, took her hand in his and said how proud and delighted he and Barbara were to welcome her into the family. “I know it’s a cliché, but we really have gained another wonderful daughter.”

Barbara had the last word. She said the celebrations couldn’t have happened without Laurent and Hugh and all their hard work. She proposed a toast to them, and Cyn started the applause.

After the speeches, Joe disappeared to the loo. Harmony, whom Barbara had put at a table full of Cyn and Jonny’s university friends, came over and helped herself to Joe’s seat. As ever, she looked spectacular. She was wearing a full-length halter-neck dress in scarlet silk. “Everybody’s talking about you and the jar of kimchee,” she said. “I laughed so much I thought I was going to wet myself.” She leaned forward and sniffed. “God, you’re still pretty strong.”

“Really? Joe said it was just a slight aroma.”

“Depends on your definition of slight, I suppose.” She looked across at Flick, who was chatting to a group of elderly relatives. “She looks so happy.”

“So do you,” Cyn said, deciding Harmony looked more than just beautiful. She looked positively radiant. For once she didn’t have a cigarette in her hand. “I know—you’ve had some news from the Home Office, haven’t you?”

“We have.” She started fiddling with the napkin Joe had left on the table. “But it’s not what you think.” She paused. “Laurent has to go back. The Home Office has said there is no reason to give him asylum since the troubles in Tagine are over.”

Cyn had no idea what to say or how to comfort her. “I am so sorry. I was sure Hugh’s contact would be able to pull a few strings.”

“He did his best, but he couldn’t help. He said he was very sorry.”

“I don’t understand,” Cyn said. “Why aren’t you more upset?”

“I’ve decided to go back with him.”

“How do you mean? What, for a holiday?”

“No, for good.”

“Don’t be silly,” Cyn laughed.

“I’m not. I’m serious.”

“Yeah, right. Come on, you’d hate it. How would you survive without Donna Karan and Joseph round the corner? And what about the business?”

“I’m leaving Atahualpa to run it and when the renovation work is finished on the Holland Park house I’m going to rent it out.”

Cyn felt her laughter disappear. “Bloody hell, you’re actually serious, aren’t you?”

Harmony nodded. “Deadly. You know how unsettled I’ve been lately.” She abandoned her napkin fiddling and looked directly at Cyn. “I just felt my life lacked purpose. Well, now I think I’ve found it. Brandy Weintraub, you know, who’s married to Barney, the film producer—well, she’s setting up a charity to help the schools and hospitals in Tagine get back on their feet. Laurent’s so excited. He can’t wait to get back and help rebuild his country, and I want be there with him.”

“So what will you do?”

She shrugged. “Mop hospital floors, work in school kitchens. I don’t care.”

“But you don’t go anywhere without straightening irons and a tube of Beauty Flash Balm.”

“There’s a first time for everything.”

Cyn squeezed her hand. “You’re my best friend. I love you, and I don’t want you to go.”

“You’re my best friend and I love you, too. But we’ll phone and e-mail and I’m definitely coming back here to have the baby.”

“Baby?” Cyn cried. “You’re pregnant?”

Harmony nodded.

“Omigod.” Cyn threw her arms round her.

“Six weeks. Isn’t it wonderful?”

Cyn felt her eyes filling up. “It’s better than wonderful, it’s bloody brilliant, that’s what it is. I wondered why you weren’t smoking. God, Laurent must be over the moon.”

“Just a bit. Since I told him, he’s barely stopped singing ‘La Vie en Rose.’ ”

“Oh, this is fab, just fab.” Cyn carried on hugging Harmony. “So, you’ll come back for lots of holidays, then?”

“Lots. I promise. Plus I don’t intend to completely neglect the business.”

“And Joe and I and Hugh can come and see you?”

“Of course you can. Once we’re settled, all of you can come for weeks, entire summers and Christmases if you want.”

Cyn hesitated for a moment. She was desperate to tell Harmony she and Joe were getting married, but she felt it would be disloyal to her parents. In the end she decided she would burst if she didn’t say something.

“Maybe Joe and I could even have our wedding there. On the beach perhaps.”

Harmony pulled away, looked at her and blinked. “You’re getting married?”

Cyn gave a series of excited nods.

“Oh, Cyn. I am so happy for you. For both of you. From what I’ve seen, Joe’s a great bloke. And I know he’ll make you happy. God, I can’t believe we’re both getting our lives sorted out. Come ’ere.” More tight hugging and back patting.

“Listen, I’m going to tell Hugh in a minute, but not a word to Mum and Dad until after today. They’ll only get up and make an announcement, and I don’t want to upset Jonny and Flick.”

“Don’t worry,” Harmony said. “I won’t say a dickey bird.” She paused. “Cyn, don’t take this the wrong way, but I’m going to let go of you now. It’s just that I’m worried your fumes might be getting to the baby.”

By now Jonny had grabbed Grandma Faye and was leading her onto the dance floor. “Do you know ‘Chattanooga Choo-Choo’?” she called out to the bandleader—the Lima Dreamers had left after dinner and been replaced by a more traditional dance band. “You’ve got it,” he said. The band struck up. Arthritis or no arthritis, after two cherry brandies, Grandma Faye was cutting a rug like a youngster. Jonny could barely keep up with her, but that was mainly because he had two left feet. After a couple of minutes, Barbara and Mal joined them.

“I hope we look as good as that in thirty years,” Joe said.

“Yeah, but suppose I’m all saggy and fat. Will you still fancy me?”

“Cyn, if I can sit here thinking how much I want to marry you when you smell like a city dump, I can cope with anything.”

“But you said I didn’t smell,” she protested. “You said it was just a faint aroma.”

“Aroma, stench . . . who cares?” he grinned. She tried to land a playful thump on his arm, but he caught her wrist. “Come on, let’s dance. They’re about to play our song.”

“But we don’t have a song,” she said, “apart from ‘It’s a Small World.’ ”

He started laughing. “Believe me, it’s not that. I’ve asked the band to play something really special.”

“Oh, I get it. Very funny. You’ve persuaded the singer to come on and do ‘Lady in Red,’ only you’ve gotten him to change the words to: ‘I’ll never forget the way you

smell

tonight.’ ”

He had to practically drag her onto the dance floor. As the music started, he took her in his arms. She rested her head on his shoulder. The band was playing ” ’Til There Was You.”

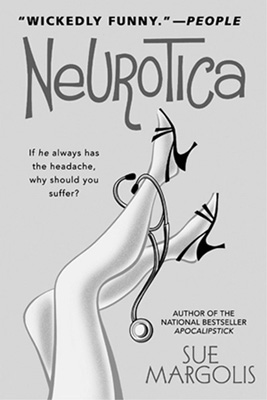

Don’t miss

SUE MARGOLIS’S

other novels

NEUROTICA

SPIN CYCLE

APOCALIPSTICK

BREAKFAST AT STEPHANIE’S

Please turn the page for previews of:

NEUROTICA

AND

APOCALIPSTICK

NEUROTICA

On-Sale Now . . .

Dan Bloomfield stood in front of the full-length bathroom mirror, dropped his boxers to his ankles, moved his penis to one side to get a better look and stared hard at the sagging, wrinkled flesh which housed his testicles. Whenever Dan examined his testicles—and as a hypochondriac he did this several times a week—he thought of two things: the likelihood of his imminent demise; and the cupboard under the stairs in his mother’s house in Finchley.

It was a consequence of the lamentable amount of storage space in her unmodernized fifties kitchenette that Mrs. Bloomfield had always kept hanging in the hall cupboard, alongside the overcoats, macs and umbrellas, one of those long string shopping bags made pendulous by the weight of her overflow Brussels sprouts. From the age of thirteen, Dan referred to this as his mother’s scrotal sac.

These days Dan reckoned his own scrotal sac was a dead ringer for his mother’s. His bollocks couldn’t get any lower. Dan supposed lower was OK at forty; death on the other hand was not.

By bending his knees ever so slightly, shuffling a little closer to the mirror and pulling up on his scrotum he could get a better view of its underside. It looked perfectly normal. In fact the whole apparatus looked perfectly normal. There was nothing he could see, no sinister lumps, bumps or skin puckering which suggested impending uni-bollockdom, or that his wife should start bulk-buying herrings for his funeral. Then, suddenly, as he squeezed his right testicle gently between his thumb and forefinger, it was there again, the excruciating stabbing pain he had felt as he crossed his legs that morning in the editors’ daily conference.

Anna Shapiro, Dan’s wife, needed to pee right away. She knew because she had just been woken up by one of those dreams in which she had been sitting on the loo about to let go when suddenly something in her brain kicked in to remind her that this would not be a good idea, since she was, in reality, sprawled across the brand-new pocket-sprung divan on which they hadn’t even made the first payment. Looking like one of those mad women on the first day of the Debenhams sale, she bolted towards the bathroom. Here she discovered Dan rolling naked on the floor, clutching his testicles in one hand and his penis in the other with a look of agony on his face which she immediately took for sublime pleasure.

As someone who’d been reading “So you think your husband is a sexual deviant”–type advice columns in women’s magazines since she was twelve, Anna knew a calm, caring opening would be best.

“Dan, what the fuck are you up to?” she shrieked. “I mean it, if you’ve turned into some kind of weirdo, I’m putting my hat and coat on now. I’ll tell the whole family and you’ll never see the children again and I’ll take you for every penny. I can’t keep up with you. One minute you’re off sex and the next minute I find you wanking yourself stupid at three o’clock in the morning on the bathroom floor. How could you do it on the bathroom floor? What if Amy or Josh had decided to come in here for a wee and caught you?”

“Will you just stop ranting for one second, you stupid fat bitch. Look.”

Dan directed Anna’s eyes towards his penis, which she had failed to notice was completely flaccid.

“I am not wanking. I think I’ve got bollock cancer. Anna, I’m really scared.”

Relieved? You bet I was bloody relieved. God, I mean for a moment there last night, when I found him, I actually thought Dan had turned into one of those nutters the police find dead on the kitchen floor with a plastic bag over their head and a ginger tom halfway up their arse. Of course, it was no use reminding him that testicular cancer doesn’t hurt. . . . What are you going to have?”

As usual, the Harpo was full of crushed-linen, telly-media types talking Channel 4 proposals, sipping mineral water and swooning over the baked polenta and fashionable bits of offal. Anna was deeply suspicious of trendy food. Take polenta, for example: an Italian au pair who had worked for Dan and Anna a few years ago had said she couldn’t understand why it had become so fashionable in England. It was, she said, the Italian equivalent of semolina and that the only time an Italian ate it was when he was in school, hospital or a mental institution.

Neither was Anna, who had cellulite and a crinkly post-childbirth tummy flap which spilled over her bikini briefs when she sat down, overly keen on going for lunch with Gucci-ed and Armani-ed spindle-legged journos like Alison O’Farrell, who always ordered a green salad with no dressing and then self-righteously declared she was too full for pudding.

But as a freelance journalist, Anna knew the importance of sharing these frugal lunches with women’s-page editors. These days, she was flogging Alison at least two lengthy pieces a month for the

Daily Mercury

’s “Lifestyles” page, which was boosting her earnings considerably. In fact her last dead-baby story, in which a recovering postnatally depressed mum (who also just happened to be a leggy 38 DD) described in full tabloid gruesomeness how she drowned her three-month-old in the bath, had almost paid for the sundeck Anna was having built on the back of her kitchen.

Dan, of course, as the cerebral financial editor of

The Vanguard,

Dan, who was probably more suited to academia than Fleet Street, called her stuff prurient, ghoulish voyeurism and carried on like some lefty sociology student from the seventies about those sorts of stories being the modern opiate of the masses. Anna couldn’t be bothered to argue. She knew perfectly well he was right, but, like a lot of lefties who had not so much lapsed as collapsed into the risotto-breathed embrace of New Labour, she had decided that the equal distribution of wealth starting with herself had its merits. She suspected he was just pissed off that her tabloid opiates earned her double what he brought home in a month.

But what about Dan’s cancer?” Alison asked, shoving a huge mouthful of undressed radicchio into her mouth and pretending to enjoy it.

“Alison, I’ve been married to Dan for twelve years. He’s been like this for yonks. Every week it’s something different. First it was weakness in his legs and he diagnoses multiple sclerosis, then he feels dizzy and it’s a brain tumor. Last week he decided he had some disease which, it turns out, you only get from fondling sheep. Alison, I can’t tell you the extent to which no Jewish man fondles sheep. He’s a hypochondriac. He needs therapy. I’ve been telling him to get help for ages, but he won’t. He just sits for hours with his head in the

Home Doctor

.”

“Must be doing wonders for your sex life.”

“Practically nonexistent. He’s too frightened to come in case the strain of it gives him a heart attack, and then if he does manage it he takes off the condom afterwards, looks to see how much semen he has produced—in case he has a blockage somewhere—then examines it for traces of blood.”

As a smooth method of changing the subject, Alison got up to go to the loo. Anna suspected she was going to chuck up her salad. When she returned, Anna sniffed for vomit, but only got L’Eau d’Issy. “Listen, Anna,” Alison began the instant her bony bottom made contact with the hard Phillipe Starck chair. “I’ve had an idea for a story I think just might be up your street.”

Dan bought the first round of drinks in the pub and then went to the can to feel his testicle. It was less than an hour before his appointment with the specialist. The pain was still there.

Almost passing out with anxiety, he sat on the lavatory, put his head between his knees and did what he always did when he thought he was terminally ill: he began to pray. Of course it wasn’t real prayer, it was more like some kind of sacred trade-union negotiation in which the earthly official, Dan, set out his position—i.e., dying—and demanded that celestial management, God, put an acceptable offer on the table—i.e., cure him. By way of compromise, Dan agreed that he would start going to synagogue again—or church, or Quaker meeting house, if God preferred—as soon as he had confirmation he wasn’t dying anymore.

Mr. Andrew Goodall, the ruddy-complexioned former rugby fly-half testicle doctor, leaned back in his leather Harley Street swivel chair, plonked both feet on top of his desk and looked at Dan over half-moon specs.

“Perfectly healthy set of bollocks, old boy,” he declared.

Kissed him? Dan could have tongue-wrestled the old bugger.

“But what about all this pain I’ve been getting?”

“You seemed perfectly all right when I examined you. I strongly suspect this is all psychosomatic, Mr. Bloomfield. I mean, I could chop the little blighter orf if you really want me to, but I suspect that if I did, in six months you’d be back in this office with phantom ball pain. My advice to you would be to have a break. Why not book a few days away in the sun with your good lady? Alternatively, I can prescribe you something to calm you down.”

Dan had stopped listening round about “psychosomatic.” The next thing he knew he was punching the air and skipping like an overgrown four-year-old down Harley Street toward Cavendish Square. He, Dan Bloomfield, was not dying. He, Dan Bloomfield, was going to live.

With thoughts of going to synagogue entirely forgotten, he went into John Lewis and bought Anna a new blender to celebrate. One can only imagine that God sighed and wondered why he had created a world full of such ungrateful bleeders.