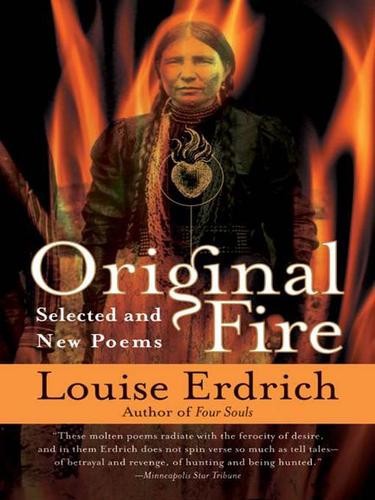

Original Fire

Selected and New Poems

To Pallas

The same Chippewa word is used both for flirting and hunting game, while another Chippewa word connotes both using force in intercourse and also killing a bear with one’s bare hands.

——

R. W. Dunning,

Social and Economic Change Among the Northern Ojibwa

(1959)

We have come to the edge of the woods,

out of brown grass where we slept, unseen,

out of knotted twigs, out of leaves creaked shut,

out of hiding.

At first the light wavered, glancing over us.

Then it clenched to a fist of light that pointed,

searched out, divided us.

Each took the beams like direct blows the heart answers.

Each of us moved forward alone.

We have come to the edge of the woods,

drawn out of ourselves by this night sun,

this battery of polarized acids,

that outshines the moon.

We smell them behind it

but they are faceless, invisible.

We smell the raw steel of their gun barrels,

mink oil on leather, their tongues of sour barley.

We smell their mothers buried chin-deep in wet dirt.

We smell their fathers with scoured knuckles,

teeth cracked from hot marrow.

We smell their sisters of crushed dogwood, bruised apples,

of fractured cups and concussions of burnt hooks.

We smell their breath steaming lightly behind the jacklight.

We smell the itch underneath the caked guts on their clothes.

We smell their minds like silver hammers

cocked back, held in readiness

for the first of us to step into the open.

We have come to the edge of the woods,

out of brown grass where we slept, unseen,

out of leaves creaked shut, out of hiding.

We have come here too long.

It is their turn now,

their turn to follow us. Listen,

they put down their equipment.

It is useless in the tall brush.

And now they take the first steps, now knowing

how deep the woods are and lightless.

How deep the woods are.

At one time your touches were clothing enough.

Within these trees now I am different.

Now I wear the woods.

I lower a headdress of bent sticks and secure it.

I strap to myself a breastplate of clawed, roped bark.

I fit the broad leaves of sugar maples

to my hands, like mittens of blood.

Now when I say

come

,

and you enter the woods,

hunting some creature like the woman I was,

I surround you.

Light bleeds from the clearing. Roots rise.

Fluted molds burn blue in the falling light,

and you also know

the loneliness that you taught me with your body.

When you lie down in the grave of a slashed tree,

I cover you, as I always did.

Only this time you do not leave.

The antelope are strange people…they are beautiful to look at, and yet they are tricky. We do not trust them. They appear and disappear; they are like shadows on the plains. Because of their great beauty, young men sometimes follow the antelope and are lost forever. Even if those foolish ones find themselves and return, they are never again right in their heads.

——

Pretty Shield, Medicine Woman of the Crows

transcribed and edited by Frank Linderman (1932)

All night I am the doe, breathing

his name in a frozen field,

the small mist of the word

drifting always before me.

And again he has heard it

and I have gone burning

to meet him, the jacklight

fills my eyes with blue fire;

the heart in my chest

explodes like a hot stone.

Then slung like a sack

in the back of his pickup,

I wipe the death scum

from my mouth, sit up laughing

and shriek in my speeding grave.

Safely shut in the garage,

when he sharpens his knife

and thinks to have me, like that,

I come toward him,

a lean gray witch

through the bullets that enter and dissolve.

I sit in his house

drinking coffee till dawn

and leave as frost reddens on hubcaps,

crawling back into my shadowy body.

All day, asleep in clean grasses,

I dream of the one who could really wound me.

Not with weapons, not with a kiss, not with a look.

Not even with his goodness.

If a man was never to lie to me.

Never lie me.

I swear I would never leave him.

He (my captor) gave me a bisquit, which I put in my pocket, and not daring to eat it, buried it under a log, fearing he had put something in it to make me love him.

—From the narrative of the captivity of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, who was taken prisoner by the Wampanoag when Lancaster, Massachusetts, was destroyed, in the year 1676

The stream was swift, and so cold

I thought I would be sliced in two.

But he dragged me from the flood

by the ends of my hair.

I had grown to recognize his face.

I could distinguish it from the others.

There were times I feared I understood

his language, which was not human,

and I knelt to pray for strength.

We were pursued by God’s agents

or pitch devils, I did not know.

Only that we must march.

Their guns were loaded with swan shot.

I could not suckle and my child’s wail

put them in danger.

He had a woman

with teeth black and glittering.

She fed the child milk of acorns.

The forest closed, the light deepened.

I told myself that I would starve

before I took food from his hands

but I did not starve.

One night

he killed a deer with a young one in her

and gave me to eat of the fawn.

It was so tender,

the bones like the stems of flowers,

that I followed where he took me.

The night was thick. He cut the cord

that bound me to the tree.

After that the birds mocked.

Shadows gaped and roared

and the trees flung down

their sharpened lashes.

He did not notice God’s wrath.

God blasted fire from half-buried stumps.

I hid my face in my dress, fearing He would burn us all

but this, too, passed.

Rescued, I see no truth in things.

My husband drives a thick wedge

through the earth, still it shuts

to him year after year.

My child is fed of the first wheat.

I lay myself to sleep

on a Holland-laced pillowbeer.

I lay to sleep.

And in the dark I see myself

as I was outside their circle.

They knelt on deerskins, some with sticks,

and he led his company in the noise

until I could no longer bear

the thought of how I was.

I stripped a branch

and struck the earth,

in time, begging it to open

to admit me

as he was

and feed me honey from the rock.

The barred owls scream in the black pines,

searching for mates. Each night

the noise wakes me, a death

rattle, everything in sex that wounds.

There is nothing in the sound but raw need

of one feathered body for another.

Yet, even when they find each other,

there is no peace.

In Ojibwe, the owl is Kokoko, and not

even the smallest child loves the gentle sound

of the word. Because the hairball

of bones and vole teeth can be hidden

under snow, to kill the man who walks over it.

Because the owl looks behind itself to see you coming,

the vane of the feather does not disturb

air, and the barb is ominously soft.

Have you ever seen, at dusk,

an owl take flight from the throat of a dead tree?

Mist, troubled spirit.

You will notice only after

its great silver body has turned to bark.

The flight was soundless.

That is how we make love,

when there are people in the halls around us,

clashing dishes, filling their mouths

with air, with debris, pulling

switches and filters as the whole machinery

of life goes on, eliminating and eliminating

until there are just the two bodies

fiercely attached, the feathers

floating down and cleaving to their shapes.