Oscar Wilde and the Vatican Murders (23 page)

Read Oscar Wilde and the Vatican Murders Online

Authors: Gyles Brandreth

‘I

shall be honoured. I am fond of my own voice. Is a “colloquy” the usual form?’

‘Only

when we have guests. Otherwise we eat in silence — as we would in a Capuchin

friary, with one of us reading out loud to the others.’

‘And

you are the reader as a rule?’ asked Oscar.

‘This

is the

circolo inglese.

The reading is always in English, so, yes, I am

usually the reader.’

‘And

what do you read? Sacred texts?’

‘Of a

kind. Recently we have been concentrating on the works of Arthur Conan Doyle!

We are devotees of the great Sherlock Holmes. Look on the sideboard — there,

alongside Cardinal Newman’s

Apologia Pro Vita Sua,

signed by the author,

you will find my copies of

A Study in Scarlet

and

The Sign of Four,

first

editions, of course.’

Breakspear

bowed towards me unctuously. I felt even happier that I had positioned myself

as far from him as possible.

We had

all found our places around the table:

Cesare

Verdi, standing by the sideboard, rang the sanctus bell and the party fell

silent. After a moment’s pause, Monsignor Felici invited Monsignor Breakspear

to say grace.

‘Benedic,

Domine, nos et haec tua dona quae de tua largitate sumus sumpturi. Per Christum

Dominum nostrum. Ad coenam vitae aeternae perducat nos, Rex aeternae gloriae.

Amen.’

It was

a grace I knew well, from my schooldays. Breakspear intoned it sonorously and

offered me a knowing smile at its conclusion. All but Father Bechetti joined

in the ‘Amen’ and we took our seats.

I have

to report that the feast spread out before us would have gladdened the heart of

the greediest schoolboy.

‘Help

yourselves, gentlemen,’ said Felici jovially. ‘Don’t stand on ceremony. The tea

in the pots on the table is Darjeeling. If you prefer something lighter, Cesare

will prepare you a special pot of Earl Grey.’

Cesare

Verdi stood hovering at my shoulder with a silver milk jug in his hand. “Ome

from ‘ome, sir, eh?’

As he

said those words, quite unexpectedly my mind’s eye was suddenly filled with a

vision of my darling wife, Touie. She was seated at the fireside in the front

parlour of the little house we had lived in during the first months of our

marriage. She was toasting muffins for me on the fire.

Felici

roused me from my reverie. ‘Dr Conan Doyle, we know you and your work. We all admire

it. Father Bechetti understands English and Brother Matteo, though he may not

speak English as well as some of us, is learning the language — slowly. I know

that both of them have sat at this table and listened to your stories with deep

pleasure.’

The

bearded Capuchin, seated between me and Felici, nodded to each of us, benignly.

He murmured,

‘Si,’

and then returned his attention to buttering a scone

for Father Bechetti.

‘And Mr

Wilde,’ continued the Monsignor, ‘we know you and your reputation. We look

forward to discovering your works in due course.’ Oscar smiled. ‘We are so

delighted at the chance that has brought you both to our table. You are most

welcome, gentlemen.’

‘We

know you,’ echoed Monsignor Breakspear, looking from Oscar to me, ‘and, because

we read the English newspapers, we feel that we know you quite well — but do

you know us?’ He looked directly at me and raised his heavy eyebrows. ‘Dr Conan

Doyle knows me, of course. We were at school together. But Mr Wilde knows none

of us.’ He turned towards Monsignor Felici on his right. ‘Perhaps, before our

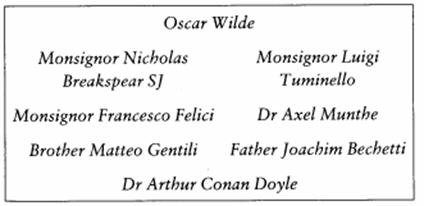

“colloquy”, we should introduce ourselves?’

Oscar

leant across the table and placed his hand on Breakspear’s wrist. ‘There is no

need, Monsignor. I know who you are.’ Oscar looked around the table and smiled,

widening his shining eyes. ‘I know who you all are,’ he said, sitting upright

and resting his elbows on the table’s edge. He brought the tips of his fingers

together and held them against his chin, as if in prayer. ‘Indeed, I realise

now that I have met you before, every one of you. It was here, at St Peter’s,

fifteen years ago. You may not recall the occasion, but I do. I was twenty-two

and I had the privilege — the blessing — of an audience with Pope Pius IX. It

was in one of the corridors close to the Sistine Chapel, only a few yards, I

suppose, from where we are seated now. I remember how we stood in line, we pilgrims,

waiting for the Holy Father. We waited for an hour, at least. And then he came.

He was old and frail —it was not long before his death. He was not alone, of

course. You were all in attendance. I can picture you now, hovering around him,

anxiously, as he made his way along the line. I was at the end of the line,

standing next to a garrulous Englishwoman and a young girl and a Capuchin

friar.’

I

looked at Brother Matteo. He had put down his knife and was listening

attentively, but his face betrayed no emotion.

‘I

remember the girl vividly,’ Oscar continued. ‘She was very beautiful, with hair

the colour of moonbeams and eyes the colour of cornflowers. And I remember what

Pio Nono said when he had blessed her and raised her from her knees and lifted

her veil to see her face. I recollect his words exactly. He said: “Look on this

child and give thanks. She is pure innocence. She is a lamb of God, surrounded

by the seven deadly sins.” I imagine that you, gentlemen, are the deadly sins

and that she is the beautiful girl in that painting on the wall. Is her name

Agnes? I am sure that it must be.’

14

The seven deadly sins

L

ife,

I have found, is infinitely stranger than anything that the mind of man could

invent. We would not dare to conceive the things that are really mere commonplaces

of existence. If you and I, dear reader, could fly out of the window hand in

hand, and hover over a great city, such as London or Rome, gently removing the

roofs and peeping in at the queer things that are going on, the strange

coincidences, the cross-purposes, the wonderful chains of events, working

through generations, and leading to the most outré results, it would make all

fiction with its conventionalities and foreseen conclusions most stale and

unprofitable.

When

Oscar had finished speaking, I sat marvelling at what he knew and how he had

discerned it. The heavy silence that greeted his remarks suggested to me that

my remarkable friend had been correct in each of his surmises.

I

looked about the table. Brother Matteo had his eyes fixed on Father Bechetti

opposite him. The old priest had his eyes closed and a curious smile upon his

face. The three Monsignors gazed steadily into the middle distance.

Eventually,

Cesare Verdi, standing by the sideboard, broke the silence. ‘More tea,

gentlemen?’

‘Thank

you,’ said Oscar. ‘More tea would be delightful.’

Monsignor

Felici turned in his chair to look up at the painting of the girl that hung in

a simple frame between the gasoliers on the wall behind him. ‘She is very

beautiful, as you say, Mr Wilde. It is some years since Father Bechetti

painted her. It is some years since he painted anything. But it is a wonderful

piece of work — possibly his finest. That is why we treasure it. The girl’s

face, of course, is the face of the Blessed Virgin in Michelangelo’s

Pietà.

I

am sure that is why people feel that they recognise her when they see her.’

The Monsignor turned back to look at Oscar. ‘We have the sculpture here, you

know, in the basilica, in the first chapel on the right. It is the only work

that Michelangelo ever signed — his masterpiece.’

Oscar

said nothing. Cesare Verdi passed around the table, pouring out fresh tea. In

the hush that filled the dining room once more, Monsignor Felici chuckled

softly to himself and contemplated the half-eaten custard tart that sat upon

his plate. Then he raised his head and, narrowing his eyes and pursing his

lips, he lifted his replenished cup of tea and raised it to Oscar.

‘And as

for the seven deadly sins, Mr Wilde, only five papal chaplains are ever

allocated cells here in the sacristy. There’s not room for more. There were

just five of us here in Pio Nono’s day. There are just five of us here now.’

Oscar

looked directly into the Monsignor’s eyes. ‘With the sacristan it’s six. And

with Pio Nono himself it would have been seven.’

‘What

are you suggesting, Mr Wilde?’

‘That

the Holy Father was a humble man — with a sense of humour. Even during my brief

audience I recognised both those qualities in him. He would have acknowledged

his own sinfulness. He counted himself as one of the “seven deadly sins”.’

Angrily,

Felici pushed his chair back from the table. His face had darkened and his

jowls shook. ‘The Holy Father was human. He was not above the stain of sin—’

As he

spoke, he began to struggle to his feet. Brother Matteo, seated on his right,

put out a gentle hand to restrain him.

‘Non

affoga colui che cade in acqua, ma affoga chi male incappa.’

[4]

Breakspear,

on Felici’s left, also put out a restraining hand. He looked directly into his

colleague’s eyes. ‘We are unmasked, Francesco, but we are not undone. Mr Wilde

has uncovered our secret. Does it matter? It is a very small secret, after

all.’

‘What

business is it of his?’

‘None,

I’m sure, but since he has stumbled upon it, let us accept what has occurred

with a good grace.’

‘It is

an invasion of our privacy,’ protested Felici.

‘Perhaps,

but does it signify? We have nothing to hide.’

Oscar

sat upright at the head of the table. I noticed that the flush in his cheeks of

a moment before had disappeared. His face had resumed its customary pallor and

his eyes had lost their gleam. ‘I apologise, Monsignor,’ he said. ‘I intended no

harm.’

‘And

none has been done,’ answered Monsignor Breakspear. ‘Having shared our English

tea, you now share our little secret. It is a very little secret.’

‘Explain

it to him,’ said Monsignor Felici, calming himself. ‘It was a secret — that was

its charm. But it contains no deep mystery.’

‘No

mystery at all.’ Breakspear turned to Oscar. ‘It was, Mr Wilde, rather as you

suggest, a little joke of the Holy Father’s. Among our duties as the papal

chaplains-in-residence, we were — and are still — in attendance upon the Holy

Father during his audiences. In the old days, before each and every audience,

we would gather with His Holiness here in the sacristy.’