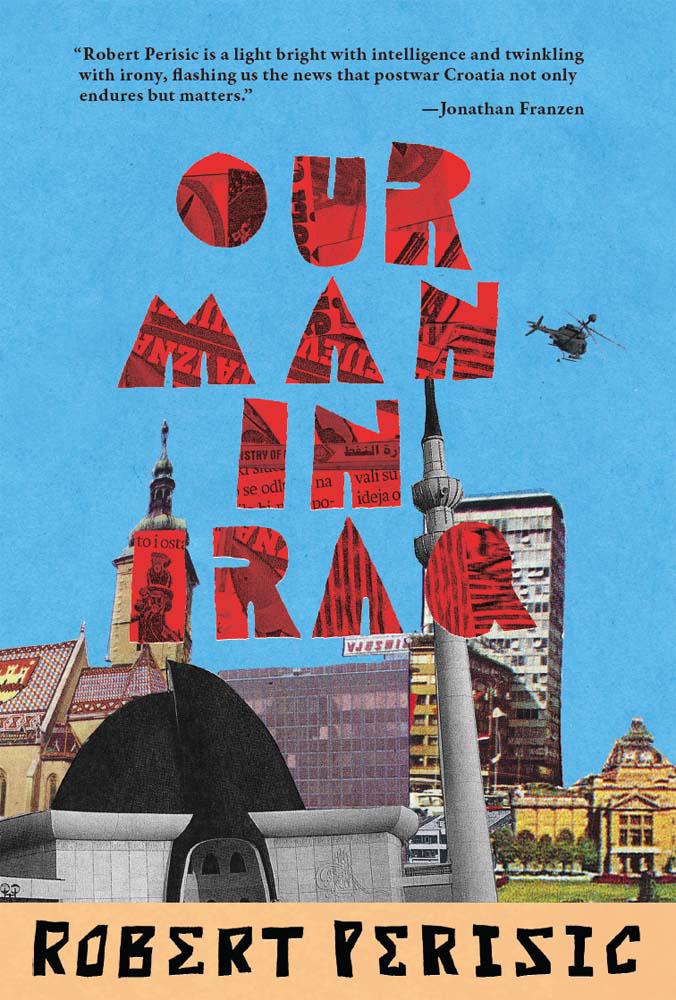

Our Man in Iraq

Authors: Robert Perisic

Published by Black Balloon Publishing

www.blackballoonpublishing.com

© 2013 by Robert Perisic

Translation © 2013 by Will Firth

All rights reserved

ISBN-13: 978-1-9367-8706-7

Black Balloon Publishing titles are distributed to the trade by

Consortium Book Sales and Distribution

Phone: 800-283-3572 / SAN 631-760X

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012919026

Cover art by Joanna Neborsky •

joannaneborsky.com

Designed and composed by Christopher D Salyers •

christopherdsalyers.com

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

BY ROBERT PERISIC

TRANSLATED FROM THE CROATIAN BY WILL FIRTH

BLACK BALLOON PUBLISHING • NEW YORK

DAY ONE

From: Boris <

[email protected]

>

To: Toni <

[email protected]

>

“Iraky peepl, Iraky peepl.”

That’s the password.

They’re supposed to answer: “I’m sorry.”

“I’m sorry.”

No sweat.

Yeah! What a view—endless columns on the road from Kuwait to Basra.

The 82nd Division’s Humvees, armored vehicles, tankers, bulldozers.

The place is full of camouflaged Yanks and Brits, the biological and chemical carnival has begun, and me, fool that I am, I haven’t got a mask. They’re expecting a chemical weapons attack and say Saddam has got

tons and tons of the shit.

I dash around with my camera and ask them all to take my photo. It’s not for keepsakes, I keep telling them, it’s for the paper.

The columns pour along King Faisal Road toward the border. Dust is always coming from somewhere.

“Iraky peepl, Iraky peepl.”

“I’m sorry.”

We continue on our way.

I keep looking to see if there are any pigeons. I’ve heard that the British biological and chemical detection team allegedly has pigeons.

There were none in the Land Rover Defender. They set up an air analyzer there that registers the smallest changes in the composition of the air. It’s a simple, soldierly device. You don’t need to think: when the indicator goes red, things are critical.

That’s what they say.

Things would be critical anyway, even without it.

Things are critical with me.

I see all those pieces of iron, pieces of steel, and I’m shut into a piece of metal myself. I can hardly breathe in here.

The 82nd Division’s Humvees. I watch them. They don’t know I’m inside.

Or do they? The British soldiers don’t want to introduce themselves. They say they’re not allowed to.

For security reasons.

This job is fucked. I say I’m a reporter from Croatia.

I tell them my name and ask if they’ve got pigeons.

I ask if it’s true that the NBC team (short for nuclear, biological, chemical), if it’s true that they’ve been given cages with pigeons.

No reply.

I tell them I’ve heard about it. Birds are apparently the best detectors of airborne toxins because they’re more sensitive than humans.

Then they reply. They say they’ve heard the story too but they’re not sure if it’s true.

They’ve got masks, like I said. But sometimes they take them off and show themselves.

I don’t know if they’re hiding the pigeons or if they really haven’t got any.

Do what you like with this. I think the bit about the pigeons is interesting.

A good illustration: pigeons or doves in Iraq, the symbol of peace and all that.

I made up the bit with the passwords.

It wasn’t New Year’s Eve, but never mind. I entered the flat carrying some plastic bags and called out in a deep voice from the door: “Father Time is here!”

She held her hand coyly over her mouth.

I put the bags down next to the fridge.

“But that’s not all,” Father Time said, standing up tall and proud. “I’ve brought some drugs too!”

I hadn’t really, but never mind.

“Oooo, lucky me, lucky me,” she chirped. “I can see you’re already smacked up.”

“Just a bit.”

“Naughty you,” she said.

“That’s just the way I am, Miss.”

She gave me a loud kiss on the cheek.

“Hey, Miss, where were you when I was shooting up? In Biology, learning about the birds and the bees?” I said to remind her who's older here.

“And pneumonia,” she said.

“Where does pneumonia come into it?” I asked.

But we were already laughing, breaking character. Not that I really knew why. Part of our love thrived on nonsense.

We could talk about non-existent drugs or whatever. I guess that element of the absurd helped us relax. One of us would say something silly and the other would laugh. We enjoyed exchanging insults.

I think she started it, long ago.

Her name was Sanja. I’m Toni.

We met after the war, under interesting circumstances: I was Clint Eastwood and she the lady in the little hat who arrived by stagecoach in this dangerous city full of rednecks. I watched as she climbed out, a fag between her lips, and the smoke and sun got in my eyes. She had a whole stack of suitcases, bound to be full of cosmetics, and I saw straight away that she’d missed her film and I’d have to save her in this one.

All right, sometimes I told the story this way because I was tired of telling the truth. Our first meeting never ceased to fascinate her. Whenever she got in a romantic mood she made me tell the story again. The beginning of love can never be recaptured. That self-presentation to the other, putting yourself in the best light, striving to be special. You play the game, you believe in it, and if it catches on, you become different.

How do you tell a story if everything is full of illusions from the beginning?

I had several versions.

One went like this: She had a red strand in her hair, green eyes, and was punkishly dressed. It’s the domain of bimbos with certain deviations in taste. And that’s how she behaved too, not quite upright, boyish, deviant; she looked a bit wasted, a look that trendy magazines called heroin chic. I took note of her when she first came to the Lonac Café, but I didn’t go up to her because her pale face revealed apathy and pronounced tiredness from the night before. You know those faces that

still radiate pubescent contempt and the influence of high school reading lists. People like that don’t want to live in a world like this, they can’t wait to cold-shoulder you when you approach—as if that’s what gives their life meaning.

At this point Sanja usually thumped me on the shoulder—“Idiot!” she would say—but she loved it when I wrapped her in long sentences.

“Anyway, I didn’t go up to her. I just watched her out of the corner of my eye and blew trails of smoke into the night.”

She liked to listen to how I eyed her from the side. That refreshed the scene, a bit like when the country celebrates its independence and patriotic myths as retold through history and official poetry ornamented with lies.

“It was in front of the Lonac Café one day: I remember her crushing out a cigarette with a heavy boot, and then she turned in her long, clinging dress, with a little rucksack on her back, and looked at me with the eyes of a young leopardess. She stalked up to me as if she’d sighted a herd of gnus.”

Basically we were so cool that this crossing of paths was almost inconsequential.

Wotcher Ned, how’s them parsnips comin’ along? How’s the harvest goin’, cuz? Hey bro, where ya been? That’s how city kids mess around with mock swagger and rural ethos! We had no idea if we fitted any of those roles. At home you’re someone’s child and you roll your eyes; you study at uni and you roll your eyes; then you go out into the world and become your own film star and you roll your eyes because no one gets your film, and you pine away unrecognized in these backwoods of Europe.

I acted in many films before they took me for my role in this serious life: I worked as a journalist and wrote about the economy. She managed to become an actress with a capital “A,” just like she always dreamed.

“How was the rehearsal?” I asked.