Owls Aren't Wise and Bats Aren't Blind (12 page)

One of the more durable myths about bats is the notion that they’re a sort of flying mouse. This belief no doubt made sense in the days when science was far more primitive—and error-prone—than it is now. For a long time now we’ve known better, however. Notwithstanding their small, furry, mouse like appearance and their German name,

Fledermaus,

bats are not close relatives of mice at all. Indeed, the connection between mice and bats is actually so tenuous that bats are much more closely related to humans than to mice.

What

are

the bat’s closest relatives? Scientific opinion varies somewhat regarding this question. The most widely accepted theory is that lemurs are the leading candidates. These small, arboreal mammals, found chiefly in Madagascar, are primitive primates. Since humans are also primates, this indeed connects our species to the bats.

Bats come in an extremely wide range of sizes. In recognition of that fact, all bats are divided into two groups, Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera. The Megachiroptera—the megabats or large bats—are fruit bats. These bats of the Old World tropics seek their food by sight rather than by echolocation. They include the world’s largest bats, the so-called flying foxes; the biggest of these, a native of Java, can weigh nearly three and a half pounds, with a wingspan that may exceed six feet.

In contrast, the micro, or small, bats, which include our North American bats, are insect-eaters and hunt by echolocation. Microbats include the world’s smallest bat, the bumblebee bat of Thailand. This tiny creature is well named, for its wingspan is less than five inches, and it weighs less than

four

one-hundredths

of an ounce.

Our North American bats, though larger than this minuscule creature, are nonetheless extremely small. Their size is deceptive because of their large wing surface, but they weigh astonishingly little. For example, the big brown bat weighs only one-half ounce, and the little brown bat one-third to one-quarter of an ounce.

In addition to being the only mammal that truly flies, bats have other unique features. For one thing, bats roost hanging head-down. Whereas other mammals, including humans, would suffer serious ill effects if they remained upside down for any length of time, this evolutionary quirk obviously suits the bat very well. In addition to turning the world upside down for the duration of the long summer daylight hours, hibernating bats may spend weeks—even months—roosting with their heads down.

This unusual behavior is made possible by physical and chemical adaptations in the bat’s body that restrict the flow of blood to the head. In turn, hanging head-down offers bats the advantage of being able to see approaching danger and to spring into instant flight. No doubt this evolutionary twist has enhanced bat survival over millions of years.

Even in their reproductive habits, bats display unique qualities. Most of our bats bear a single young per year, although some species may have two. The baby bat, known as a pup, weighs at birth a quarter of its mother’s weight. The human equivalent would be a 120-pound woman giving birth to a thirty-pound baby! As an added feature found only in bats, the mother nurses her young with teats on the

sides

of her body, rather than the front.

Depending somewhat on the species, the mother bat may carry her pup, clinging to her furry skirts, on her nightly hunting forays. As the pup grows and becomes too much of a burden, the mother simply leaves it hanging in the roost. After about a month, the bat pup is able to take flight and forage for itself. Incidentally, one of the great mysteries of bat biology is how a mother can locate her pup among millions of bats in some of the largest bat caves.

Although bats have a low reproductive rate, they make up for it by a long life span; some bats have actually been known to live twenty to thirty years, a remarkably long life for such a small mammal.

Many North American bats migrate with the onset of winter weather. Some travel only relatively short distances to a cave, abandoned mine, or other suitable place to spend the winter where a fairly even temperature is maintained. Others may migrate several hundred miles to find winter quarters. Although hibernating bats need a temperature without wide fluctuations, they possess yet another unique feature to protect them during their winter rest: some hibernating bat species can actually survive with a body temperature as low as 23 degrees Fahrenheit.

There are about a thousand species of bats worldwide—about 25 percent of all known mammal species. Of these, forty-three species are native to North America. Sadly, about half of these are in severe decline, regarded either as threatened or endangered. Most of this decline is attributable to human activity. Partly it’s due to carelessness or misunderstanding; such things as pesticide use, habitat destruction, development, and human disturbance—particularly during hibernation—have all taken their toll. Disturbance is especially destructive; simply agitating hibernating bats by entering their winter quarters may cause them to burn up as much as sixty-seven days’ worth of energy reserves.

Even worse has been the vandalism and wanton destruction of bats and their habitat. Some people have even gone so far as to dynamite caves and abandoned mines where bats roost or hibernate, and a variety of other methods have been used to harass and kill these harmless and beneficial creatures. The bright side of this is that education is having an effect, and more and more people are coming to appreciate how useful and amazing bats truly are. This gives us at least some hope that the decline of our North American bats can be halted and perhaps even reversed—a goal we should all strive for.

7

It Isn’t Acting: The Opossum

MYTHS

Opossums pretend to be dead when danger threatens.

Opossums pretend to be dead when danger threatens.

Opossums hang by their tails while they sleep.

Opossums hang by their tails while they sleep.

Young opossums travel by hanging by their tails from their mother’s tail.

Young opossums travel by hanging by their tails from their mother’s tail.

WE TEND TO THINK OF MARSUPIALS IN TERMS OF THE CLASSIC KANGAROO, BOUNCING ALONG WITH ITS JOEY’S HEAD VIEWING THE WORLD OVER THE TOP OF ITS MOTHER’S POUCH. Marsupials are a diverse lot, however, as demonstrated by the opossum

(Didelphis virginiana).

As our continent’s sole representative of the marsupial order—creatures that carry their young in a pouch—the opossum is an object of considerable interest. Simply called “possum” most of the time, except in highly formal usage, this house-cat-sized creature has expanded its range greatly during the past few decades, bringing a new and interesting creature to many areas where it was previously unknown.

Despite their status as our only native marsupial, possums are best known for “playing possum,” a phrase that has become common in our language as a term for feigning such things as illness or sleep in an attempt to deceive. Actually, the common notion of playing possum is somewhat off the mark: the possum isn’t playing at all, if playing is meant as an intentional act of deception.

Possums aren’t, to use a current expression, the brightest bears in the woods, and they don’t think in terms of playing dead to deceive an enemy. When a possum is threatened, it’s likely to first show its teeth and hiss almost like an angry cat. If that fails to frighten a would-be predator, the possum may run away or climb a tree. As a last resort, however, the creature falls into a sort of catatonic state, body limp and eyes wide open. This is not a conscious act of pretending, but is really a genetically programmed reflex action. Sometimes this defensive adaptation works, and a predator loses interest in a victim that appears to be dead. Even after the threat is gone, though, the possum may remain in its comatose state for hours!

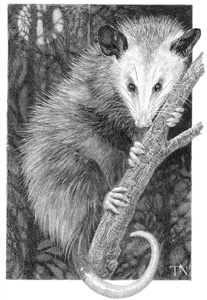

Opossum

The possum was once regarded as a creature of the South, coming north only as far as Virginia, Indiana, and Ohio. However, owing partly to a gradual warming of the climate and partly to transportation by humans, possums are now found in most of the lower forty-eight states, as well as in southern parts of some Canadian provinces.

I have a rather good idea just when possums first reached the area of Vermont’s Champlain Valley where I grew up, mainly because of a most amusing incident that occurred in my hometown. A neighbor, Basil Muzzy, went out with his hound one evening in the mid-1950s to hunt raccoons. Soon he heard his dog barking “treed” and hastened to the spot to dispatch the coon. Instead of a coon in a tree, however, he found the dog barking at an animal lying on the ground, the likes of which he’d never seen before.

The strange creature was dead, so Basil picked it up by the tail, brought it back to his car, and dropped the deceased animal on the floor of the backseat. Then he drove to the home of a friend, who he hoped would be able to identify the animal.

When Basil summoned his friend and looked into the backseat to retrieve the beast, he found—absolutely nothing! After puzzling over this for a bit, he realized that the car windows were shut, so there was no way the animal could have escaped. Accordingly, he began turning the car inside out. He finally located the object of his search—far up behind the back of the rear seat! The animal was dead, and his friend had no idea what it was, so Basil opened the trunk, dumped in the expired creature, and closed the lid. Then he drove to the house of another friend.

Upon arriving at the home of the second friend, Basil asked for his help and opened the trunk to display his curious acquisition. Nothing! Now, the trunk had no exits and contained only a spare tire without a tube in it, so it wasn’t difficult to fathom where the strange animal had gone. Basil felt around inside the tire and soon came upon the missing mammal, which he promptly hauled forth. The second friend didn’t know what it was, either, but it was obvious the creature was dead.

About that time, Basil remembered the phrase “playing possum” and began to suspect the truth. He next drove to the home of the local game warden, who quickly confirmed that the stranger was indeed a possum—seemingly dead, but still very much alive—the first one seen in those parts.

The name

opossum

is one of those adapted without much change from the Native Americans; it comes from the Algonquian

apasum,

“white animal,” and most possums, especially those farther north, are indeed a very light gray—sometimes almost white. In 1612, Captain John Smith of Pocahontas fame was the first European to send back word of this novel creature, which he described in these terms: “An Opassum hath a head like a Swine, & a taile like a Rat, and is of the Bignes of a Cat.” Captain John was evidently a keen observer, for this is a remarkably apt, if somewhat superficial, description.

Aside from a very long, pointed snout with fifty teeth, the possum’s most notable feature is its long, naked, ratlike tail. This useful appendage is prehensile, and possums are widely depicted as hanging by their tails while sleeping. This is a myth: biologists who work with possums have never seen this behavior. Possums do, however, wrap their prehensile tails around branches in order to brace themselves and steady their position in trees, using the tail almost as a third hand, and one might conceivably suspend itself by its tail very briefly. Possums don’t, however, hang by their tails for any length of time, and they certainly don’t sleep in that fashion.

If possums don’t dangle by their tails, they assuredly hang by their hind feet. This behavior is made possible by a most curious adaptation that helps them clamber about in trees, gripping branches securely. Four of the toes on each hind foot have sharp claws, but the fifth, the big toe, lacks a nail and is opposable, like a human thumb. This odd-looking digit, which appears almost as if its tip had been amputated, enables the possum to grip branches with such dexterity that it can use its front feet to gather fruit while suspended by its hind feet.

True omnivores, possums will eat virtually anything. In fact, those who know the possum well often describe it as the quintessential omnivore—a sort of walking garbage can. Possums have a reputation in story, folklore, and song for loving persimmons when the puckery fruits ripen to sweetness in the fall. True, possums do devour persimmons with gusto, but they also feed avidly on other fruit, birds’ eggs, mice, slugs, earthworms, nuts, snakes, garbage, lizards, carrion—the list goes on and on, encompassing almost everything imaginable.

Possums also seem to relish cat food. My aunt, a great cat lover, used to feed several semi-wild cats on the back porch of her Vermont farmhouse. This small porch was enclosed, but she left the door open to give the cats ready access to the tray of cat food that she regularly placed there. When my aunt opened the door to the porch one day, she was startled to see a strange creature intermingled with three or four cats, the whole crew industriously putting away the canned cat food while studiously ignoring each other.

She quickly deduced that the uninvited guest was a possum, and was a bit wary of it at first. The possum, however, continued to show up now and then, although not on a daily basis, to eat cat food, so my aunt soon became accustomed to its presence. Considering the possum’s willingness—even eagerness—to devour anything even remotely digestible, its predilection for cat food isn’t to be wondered at. Far more surprising was the apparent tolerance of cats and possum for each other. Perhaps, being of roughly equal size, neither felt threatened by the other.

Aside from being a marsupial, the central feature of possum biology is the creature’s life span. For its size, the possum is one of the shortest-lived animals in the world. Most mammals of house-cat size see a portion of their numbers live for at least three to five years, and frequently considerably more. House cats, for example, routinely live into their teens, and a few even manage to be around for a full two decades. Possums, in contrast, almost never live to be more than two years old, and most fail to make it even that far. Why is anybody’s guess. Most wild animals in captivity live considerably longer than their wild compatriots, but possums are an exception; even captive specimens rarely make it past the age of three. Wild or captive, they apparently live life in the fast lane and simply run down after two years or less.

Possums have enemies, of course. Perhaps the major cause of possum mortality, at least in more heavily settled areas, is the automobile. Possums aren’t swift when they cross highways, and often feed on roadkill, thereby exposing themselves to the same agent that did in the roadkill. Possums are also widely hunted in rural areas for their meat and fur. Still, human predation, intentional or otherwise, seems to have little impact on the possum population. So brief is the possum’s life span that much of this mortality may only substitute for other early causes of possum demise.

Much the same can probably be said of other enemies. Owls, snakes, dogs, coyotes, and assorted other predators take their toll. So do disease and parasites. None of this seems to matter much, though. Possums quickly wind down and expire, even if something else doesn’t get them first.

Considering the possum’s exceptionally brief life, how has it managed to survive for millions of years? Its lineage is an ancient one; its marsupial ancestors date back at least 85 million years, well into the age of dinosaurs, and our present-day possum split off from another opossum as far back as 75,000 years ago.

The secret of the possum’s survival seems to be its exceptional fecundity. A female possum bears her first litter when she’s only six to nine months old. If she lives long enough, she’ll have a second litter, but only a very few possums live long enough to have a third. A litter often consists of ten to fifteen young—sometimes more—and averages about nine. This combination of very early reproduction and huge litters has effectively ensured the survival of this creature and its ancestors.

As with other marsupials, possum young are born virtually in the embryonic stage. This is hardly surprising, considering that their gestation is an astonishingly brief thirteen days! The tiny newborns are only about the size of a raisin, and a whole litter can be fitted into a tablespoon. The most critical moments for a newborn possum occur when the tiny, larvalike creature must make its way about two inches to the mother’s pouch. Although most succeed, some don’t, and the latter simply die. Those that reach the pouch have an excellent chance of survival as, warm and protected, they find a teat and begin feeding. There they remain, firmly attached, for several weeks.