Pagan's Daughter (16 page)

What’s that awful noise?

‘Shh.’ His hand falls away from my face as he puts his mouth to my ear. ‘We’re going. Now.’

Now? It’s a bit early, isn’t it?

‘Before the others wake up,’ he adds, under his breath, and of course he’s right. God forbid that we should have to endure another day full of pilgrims.

Pilgrims like Gilbert, for instance. That noise must be him. Snoring.

He sounds like an ox drowning in a cesspit.

Isidore straightens, and his knees crack. (It’s a nasty moment, but no one stirs.) He hands me something— oh! What are these? My boots? I can hardly see in this light.

‘Bring them,’ he whispers.

It’s good that I didn’t really get undressed, last night. Just kicked off my boots and dived under the blankets. Now that I think about it, I didn’t even hear the others come in. I must have been dead to the world. What time is it, I wonder?

Ouch! Ah! My legs! My backside!

‘Shh.’ He’s hushing me again. Oh dear. Did I whimper? But I couldn’t help it—I’m still as stiff as a lance. Sore, too. Whoops! The door creaks. There’s a sleepy sigh; once again, however, no one moves. Perhaps no one heard us through Gilbert’s snoring.

In my hose, it’s easy to move like a fox, padding on silent feet. Yuk! These rushes! They’re all wet! (I hope no one’s been vomiting.)

‘The bags!’ I hiss, but Isidore doesn’t answer. Instead he stops at the table, and picks up two irregular black shapes.

The saddlebags, obviously.

He must have been up for a while, packing and dressing—unless he did it all last night.

I

certainly wouldn’t have noticed. I wouldn’t have noticed the Last Trump.

He leads the way through the second door, into a cramped little cloister that’s illumined by the first faint glow of daybreak. I can hear a restless bird twittering somewhere nearby. But no monks. Where are they?

‘Are the monks up?’

‘I should think so,’ he replies. ‘Didn’t you hear the bell for lauds?’

‘No.’ I was fast asleep. ‘Where are we going? To the stables?’

‘First I have to make my farewells to the Abbot.’ Isidore peers around, as if in search of something. ‘Do you remember where the stables are?’

‘Yes, but—’

‘I’ll meet you there, then. See if you can rouse one of the stable hands. There’s bound to be a few of them sleeping in the byres.’

‘Wait.’ I have to grab him. I don’t want to but I have to, because he’s already moving away. ‘I need to go somewhere first.’

You

know what I mean. ‘For a quick visit.’

‘The latrines?’

‘Yes.’

‘Go, then. Don’t dawdle.’

And off he strides, his black skirts swinging. Don’t dawdle. Right. I’ll just pull on my boots (ouch!) and— let’s see, now. Where are the latrines? Ah, yes. Over there. Pray God that nobody’s in them.

Normally you can follow your nose to a latrine, but not in this monastery. There was a latrine at Laurac, and people used to pass out in mid-flow, despite all the lavender and rosemary that was tossed around the floor. In these monastery latrines, however, you can breathe quite easily—perhaps there’s water underneath the holes.

Yes, there it is. I can hear it rippling along down there, although the light’s too poor to see anything much. I’ve been told about this kind of latrine. Fresh water in ditches, carrying the refuse away. Who would have thought that I’d actually use one?

My trickle sounds awfully loud, hitting the water. Echoing off the stone. And now what am I supposed to do? Anything? Am I allowed to use this straw? Can I throw it into the water, or am I supposed to put it somewhere else?

Maybe I won’t use the straw. I don’t really need to. I’ll just pull up my drawers, tie up my hose—there!—and be on my way.

‘Well, well, well.’

Oh God.

It’s Drogo.

‘I thought as much,’ he sneers, standing in the door-way with the dormitory candle. ‘Last night I said to myself: There’s precious little between those legs. I asked myself: Is he a girl or a eunuch? And here’s my answer.’

Stupid latrines! The running water—it must have masked his footsteps.

How long has he been watching me?

‘Nothing to say for yourself?’ He moves forward, closing the gap between us. ‘That’s all right. Women should be seen but not heard. If

you

can keep a secret, so can I.’

My pepper. My scissors.

They’re here in my purse.

‘No point making a fuss, or someone might come,’ he drawls. ‘And you don’t want

that

to happen, do you? Oops! No, you don’t.’ He grabs me with one hand as I try to push past. ‘You’re staying right here until

aaaagh

!’

Pepper, straight in the eyes. The candle falls. He’s coughing and cursing, but he’s already behind me. Run.

Run!

Out the door. Round the corner. Turn right and right again. Where next? Quick! Where am I?

Wait. I know where I am. That’s the forecourt up ahead, and the stables are on the right. It’s much lighter now, and—yes! The forecourt. With the stables over there, not far, just a short expanse of beaten earth and pray

God

that someone’s inside . . .

‘Hello?’ When I burst in, I’m greeted by the whinnying of startled horses. It’s dark in here, though—I can’t really see. Everything smells of hay and manure.

‘Hello?’

‘Who’s that?’ A sleepy voice from somewhere to the left.

‘I’m a guest.’ Quick, quick! ‘My master is Father Isidore, from Bologna. We want to leave. Now.’

‘Now?’

‘We need our horses saddled. At once.’

There’s a grunt and a rustle. Something moves over there in the corner. Light’s beginning to creep through chinks in the roof; it’s gleaming on a glossy roan hide, and glinting off—what’s that?

A hatchet?

Just what I need.

I have to go back. I have to stop that stinking, slimy scumbucket before he tells the others. Before he opens his mouth and blabs. I can do it.

After all, I’m not the only one nursing a secret around here.

Someone’s beginning to tramp past the horses, tripping over pails and cursing at rats. He’s too busy to notice if I take this hatchet. I’ll bring it straight back; I just need it for protection while I present my demands. I won’t be long.

The air in the forecourt is fresh and cool. A cock is crowing not far away, but I don’t want to think about that. I don’t want to think about fowl-houses or floppy dead chickens. I have to concentrate. I have to be strong and quick and clear in my mind. Now—here’s the first corridor. It’s like a cloister walk, with stone vaults springing up overhead. Dark as a well, but I can still make out where I’m going. Raising my hatchet, because he might be just around the next corner.

No—nothing. More corridor, with a light at the end where it opens into that little cloister. I can’t see a soul.

I can hear someone, though. Two people. Low voices, muttering.

Where are they?

As I creep along, hugging the cold, stone wall—trying to ignore the pain in my thighs (ouch!)—the voices become clearer. One of them belongs to Drogo; unless I’m mistaken, he’s still near the latrines. Is he spilling his guts? To Boniface, perhaps?

No. That’s not Boniface.

That’s Isidore.

‘. . . don’t know what you’re talking about,’ Isidore’s saying, whereupon Drogo snorts.

‘You know what I’m talking about, Father. You and that little chicken of yours, cosying up together.’

‘You’re mistaken.’

‘You want me to tell the rest of ’em? Father Boniface, maybe? I will. I will unless you make it worth my while not to.’

‘Where’s Benoit?’

‘I’ve seen your books. How many do you have— three? Maybe I’ll take one of those.’

‘Where’s Benoit?’

‘Here I am.’ Anyone would think that I’d knocked over a pile of iron pots. Isidore jumps like a rabbit. Drogo drops his candle again. They both whirl to face me. ‘Here I am, Father.’ (Swinging my hatchet.) ‘Our horses are nearly ready.’

‘Just listen to her!’ Drogo taunts. ‘She only has to open her mouth, and she betrays herself!’

‘I won’t betray myself.’ You cur. ‘And you won’t betray me either. Not if you’re smart.’

‘Oh-ho! And who’s to stop me, eh? You?’

‘Benoit,’ says Isidore, so calmly that I

know

he must be strung as tight as a

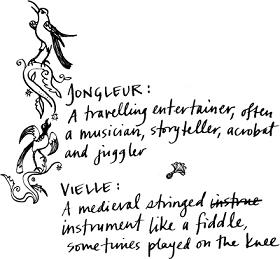

vielle

. (I think he’s worried that I’m going to throw this hatchet at Drogo’s head.) ‘Please, Benoit, let me deal with this. Something can be arranged.’

‘You’re right. Something

can

be arranged.’ And this will be the arrangement. ‘If Drogo keeps quiet about us, we’ll keep quiet about him.’ The spineless maggot’s jaw drops as I advance on him, balancing the hatchet in both hands. ‘Do you want your employer to know that you’re a heretic? Is that what you want?’

Isidore stiffens. Drogo catches his breath.

‘Because I’ll tell him, Drogo. As soon as you let drop the slightest hint about me—’

‘I’m not a heretic!’ he croaks. ‘Not any more!’ Hah! Look at him squirm. Look at him wriggle. ‘That was years ago, I swear it was! In Lombardy!’

‘Do you think Boniface would care if it was years ago? It’s a deadly sin, whenever it happened.’ And Drogo knows it too. I can tell by the way his veins stand out on his forehead. ‘Someone like Father Boniface—he wouldn’t touch you with gloves on, if he knew.’

‘You can’t tell him! You can’t!’

‘I won’t. I won’t if you keep quiet about us.’

There’s a pause. Drogo is panting. I’m worried about the rest of the pilgrims; is that the clatter of a wooden sole hitting a stone floor, in the distance?

I hope not.

‘We’ll go now.’ Come on, Father. Stir your stumps. ‘And you’d better not try to stop us, Drogo, or you’ll suffer for it.’

‘He understands,’ Isidore says suddenly. He moves past Drogo on soundless feet. ‘You understand, do you not, my son?’

‘Yes, yes.’ Drogo spits it out. ‘Damn you to hell for your sins!’

I

could

say something about being in hell already, but I won’t. I don’t have time. We must leave now, before Bremond comes looking for a place to empty his bladder.

‘You’ve a shepherd’s taste in women, Father!’ Drogo hisses after us. ‘Black as a crow, skinny as a whip and a tongue like a scorpion’s tail! Bedding her must be like bedding a scythe!’

No comment from Isidore. He probably didn’t even hear.

He’s in too much of a hurry.

You’ll find that it gets easier

. What a lie that was.

My knees won’t bend properly. My backside feels as if it belongs to someone else. My thighs would be screaming if they had mouths to do it with.

This isn’t what

I

would call easier, Isidore.

Not that you’re the slightest bit worried about me. Oh no. I can tell exactly what’s troubling you, and it’s not the state of my muscles. You’re worried about your reputation.

‘It’s all right, you know.’ In case you haven’t worked it out. ‘Drogo won’t say anything. He’ll be too frightened in case we happen to run into them all again, and say something about his murky past.’ So cheer up, can’t you? ‘He’s a coward, that one. I can smell it on him.’

Isidore says nothing. He looks very grave and thoughtful; though he’s staring straight ahead, it’s obvious that he doesn’t see the dusty road unrolling in front of us, or the little copses clustered about meandering streams, or the pathetic remnants of someone’s failed attempt to raise oats: upended stumps, piles of rocks, overgrown furrows.

His gaze is turned inwards.

‘In fact I wouldn’t be surprised if he had more to hide than the true faith.’ (I refuse to call it heresy—not when I don’t have to.) ‘I’d be willing to lay a wager that he’s been a thief in his time, with that sly look of his. And whatever happened to that old madman? Why did he disappear so suddenly? If you ask me, Drogo had something to do with it. He looks like the sort of person you get working on barges down by the wharves in Toulouse; they’re all of them exiles. It’s no coincidence that the river keeps spewing up corpses around the water mills. If you want a hired assassin, you always head for the wharves.’

Isidore remains silent. And it’s beginning to annoy me. I

refuse

to be condemned out of hand, without being given the chance to defend myself.