Pagan's Daughter (2 page)

You want this chicken?

Fine.

‘

Yowch!

’ It hits him full in the face. But he’s blocking my way; I can’t reach the hole that I got in through.

The door behind me is my only chance.

‘Get her! Stop her!’

‘Come here, you whore!’

Fat, fat, fat. They lumber like cows. I’m trampling all the green shoots, but I can’t help it—I have to reach the door—hurry, hurry!

Through

the door! Whirl around! Pull it shut, and there’s a latch! A

latch

! It’s as good as a lock!

The door shudders beneath the weight of a hurtling priest. But it’s sturdy. It’s oak. It won’t give way.

‘Open this door!’ Pounding fists. ‘

Open this door!

’

I’m sorry, are you talking to me? You and what armoured warrior, my fat friend?

Quick glance around. There’s no movement. I’m in a cloister—it’s very big—with a well in the centre of the square courtyard, and a row of columns on each of its four sides. The columns are carved with snarling, painted beasts coiled about their tops. There are doors, too, behind the columns. Lots of doors. Most of them shut.

How am I going to escape?

The church. I can see it straight ahead, on the other side of the cloister courtyard, rearing up to block the sky. If I can get into the church, I can certainly get out of it. The church of St Etienne is open to all the people of Toulouse, all the time. I just have to work out which door I should use.

‘

Open up! Do you hear me?

’ (Thump, thump.) ‘

OPEN UP!

’

I can’t stay. Someone will hear that noise, and come running. Where are the other priests? Not in church, I hope.

Now. Take a right turn.

Go

!

‘

Ooof!

’

Ouch! Ah! What happened? Where am I? I must have hit something and . . . I’m on the floor. The floor is dark stone, worn shiny. There’s a soft leather boot under a trailing black hem.

And a face, too. Staring down at me. A thin face, as white as milk. (White with shock?) A long nose. Pale, stricken eyes. Blood on his scalp.

No, not blood. Red hair.

‘Who—who are you?’ he croaks. He’s holding his stomach; I must have hurt him when I bumped into him.

I have to get away.

‘No! Wait!’ He catches my arm. Let go! Get off!

But he’s strong. He’s so strong. I can’t shake him loose. Can’t bite those long, white fingers, either, because he shifts his grip. He grabs my collar.

Bang! Bang!

‘Open the door! There’s a thief!

A thief!

’

Curse those fat priests! Smite them with the pox on their piddlers, oh God, please

help

me! When I lash out with my foot, the thin priest sidesteps. He’s still clutching my collar.

‘Shh!’ he hisses. ‘Calm down! Get in there! Hide in there!’

Who—? What—? Is he talking to

me

? One quick shove and suddenly I’m in a room off the cloister walk. A round room full of benches and hung with fine tapestries.

‘Get behind that hanging!’ he whispers. ‘Go on! Quick!’

I can’t believe it. Tapestries! Great, glittering things covered in gold stars and flying beasts. Beautiful things, like windows into heaven. But they’re too long for the walls, so I can burrow into the bunched folds piled up behind one of the benches.

It’s dark and damp and stuffy. The silk smells almost like singed hair. I can hear his voice in the distance—the redhead’s voice.

‘A girl?’ he’s saying. ‘Yes, I think I saw someone, but I didn’t know it was a girl.’

Curse him!

‘She went that way. Through that door.’

My pepper. If all else fails, I still have my pepper. Fiddling with the strings of my purse, I strain my ears, trying to make out what’s happening. Why did he hide me, that red-headed priest? Why hide me, if he was just going to turn around and betray me? But perhaps he won’t betray me. I can’t hear any footsteps. There are voices, but the voices are fading.

Unless I’m wrong, that redhead has sent his friends off in the wrong direction.

I can guess why, too. I’m not stupid. I know what priests are like. (I ought to, after what happened to my own mother.) Who hasn’t heard all the stories about priests lifting skirts? Besides which, I just crawled through a hole that must have been dug by a sinful priest. By a sinful priest in search of women.

By the red-headed priest, perhaps?

But I’m not a whore. If he tries to force

me,

I’ll scratch his eyes out. I just have to keep my wits about me. I have to be quick, and clever.

Once upon a time there was a brave and beautiful princess who escaped from a locked tower guarded by a hundred venomous serpents ...

‘Psst!’

The tapestry is twitched from my hand. There’s light again—light and air. How did he come so close? Why didn’t I hear him?

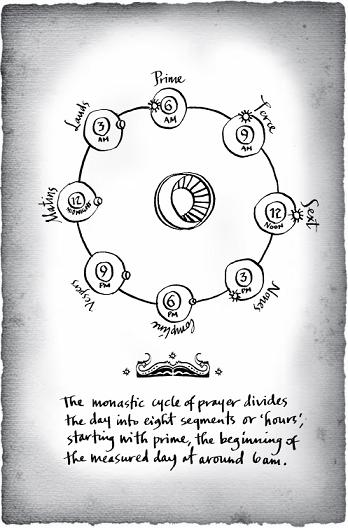

‘It’s all right,’ he says softly, stepping back as I scramble to my feet. He’s still pushing the stiff, heavy cloth to one side. (He’s so tall! He’s like a tower!) ‘You’re safe for the moment. I’ve sent them off to the kitchens,’ he continues. ‘But we don’t have much time. Nones is nearly over; they’ll all be leaving the church. You must come to the guest house, and we can talk there.’

Talk. Right.

You must think I’ve got bowels where my brains should be.

‘Please.’ His voice cracks. He sounds desperate— almost frightened. I don’t like the look on his face. You’d think he was going to faint, or something. ‘Please,’ he says, ‘you must come, we have to talk, you don’t understand—’

Whoosh

! I hit him square in the eye with my handful of pepper, and dodge his swinging arm. He shouts, but I’m out of the room already. Running for the door into the garden—and it’s ajar! It’s standing ajar!

Through the door. Over the cabbages. Past the fowl-house. Threading between the bean-stakes and . . .

. . . into the hole.

I’m safe, now. I’m safe.

They’ll never find me, if I keep my head down.

Grandmother Blanche is asleep downstairs.

She’s sitting in the big, carved chair that she brought from Laurac, her head thrown back and her mouth wide open. She’d look dead if it wasn’t for the snoring.

She has a snore like an armoured corpse being dragged across dry cobblestones.

‘

Babylonne? Is that you?

’

Curse it. Those are Aunt Navarre’s feet, up there at the top of the ladder. She’s coming down from the loft— and I’ll never make it to my bed in time.

I’ll have to slip the egg into Gran’s bed. There. Like that.

Not a moment too soon.

‘Babylonne! Where have you been?’ Aunt Navarre is in a foul mood. (As usual.) Her back must be bothering her again. ‘You’re late!’ she spits. ‘What have you been doing? Idling? Gawking?’

‘No—’

‘Don’t lie to me!’

‘I’m not.’ Quick, Babylonne. Think.

Think

. ‘I’m late because a friar was preaching near the Croix Baragnon, and the crowd was so great that it blocked the street, and I had to go around.’

‘Around? Around what? It wouldn’t have taken you

that

long to come through Rouaix Square.’

‘No, no, I went further than that. I took the Street of Joutx-Aiques, and went past La Daurade. I had to, because the friar was talking in such a loud voice that I thought I might hear some pestiferous lies of the Roman Church if I went through Rouaix Square.’

‘Hmmph.’ She’s suspicious, but she can’t catch me out. So she raises her voice above Gran’s snores, and asks about the money.

‘Here. It’s here.’ When I pull the money out of the purse at my waist, she snatches it from me.

‘There wasn’t any trouble?’ she asks.

‘No.’

‘And he gave you no more wool?’

‘He says he’ll have some on Friday. He says he’ll pay the same price if we can have it spun by this time next week.’

Aunt Navarre sniffs. She goes to the big metal-bound chest in the corner, and opens it with the key that she always carries on her belt. She’s so jealous of that key. So jealous of that chest. If you even sit on it, she’ll lay into you with an iron pot.

I suppose it’s her last link with the old life. The only thing that she saved from the Ancestral Home at Laurac, apart from Gran’s chair. Personally, I was glad to turn my back on Laurac. I didn’t want to spend my life mouldering away in that little cow-stall of a town. I’m

glad

we had to leave—even though the French did force us out. I can’t believe I survived seven long years in Laurac.

Toulouse is my spiritual home. I might not have been born here, but I belong here. Toulouse has twenty thousand people in it.

Twenty thousand people!

It’s busy and it’s bright and it’s also very brave. It won’t bend its knee to the French King. Not now. Not ever. Toulouse will

never

belong to France.

‘Where is everyone?’ This place seems so empty.

‘Where’s Sybille?’

‘Sybille and Berthe have gone to fetch water,’ Navarre replies. ‘Dulcie’s upstairs. And it’s almost time to eat, so you’d better start soaking your grandmother’s bread.’

‘What are we having?’

‘What do you think?’ A sharp retort, like a trap springing shut. ‘It’s a fast day, remember?’

Ugh. Fast days. How I hate them. But it could be worse. It could be Dulcie’s turn to cook. Dulcie’s idea of cooking is to assault the nearest turnip with a big stick and a jug of boiling water. I suppose, since she spends so much time mortifying her own flesh, she believes that we should all be mortifying ours as well.

I’m beginning to wonder if she really

did

leave her husband. If you ask me, it’s more likely that her husband left her—because he couldn’t bear to eat another glutinous lump of mysterious grey stuff.

Oops! And here she is in person. Dulcie Faure. Climbing down from the loft with a smug expression on her long ferret’s face. Sure enough, she’s moving stiffly. Like someone who’s just given herself a brisk beating with a willow switch.

I’d punch her in the nose, except that she’d probably enjoy it. She’d raise her pop-eyes to Heaven and offer up her suffering to the Lord. I always thought that Aunt Navarre was pious, but since Dulcie arrived I’ve been forced to reconsider. I don’t think even Navarre ever slept with her head on a river rock.

‘Wake up, Mother.’ Navarre gently prods Gran’s chest. ‘It’s time to eat.’

‘I’ll join you at the table,’ Dulcie announces, as if she’s bestowing on us all a gift without price, ‘though I won’t eat. Not today.’

‘You must eat something,’ Navarre frowns. ‘If you don’t, you’ll make yourself ill.’

‘It is in Christ’s hands,’ Dulcie simpers. I know what she’s thinking. She’s thinking about the

endura

. If you’re a really pious Good Christian, and you starve yourself to death, you won’t return to this vale of tears in another form. You’ll be whisked straight up to Heaven.

I’ve always wondered if Dulcie might starve herself to death one day. Why not, after all? She has a head start on the rest of us, because she obviously doesn’t like food. You can tell by her cooking.

‘

There

you are at last!’ Navarre isn’t speaking to Dulcie. She’s speaking to Sybille and Berthe, who just stumbled through the front door. ‘What took you so long?’

Berthe is crying. She’s always crying. (You tend to cry a lot, when you’re eight years old.) Her face is wet and so are her skirts. Sybille’s looking pretty damp, too. They seem to have brought most of the water back on their clothes.

Sure enough, their bucket’s half empty.

‘What happened to all the water?’ Navarre snaps, and the words tumble from Sybille’s rosebud mouth.

‘A man came near!’ she stammers. ‘He—he jostled us! He pinched my bottom!’ (What? I don’t believe it. How could you pinch Sybille’s bottom? She doesn’t

have

any bottom. You don’t, when you’re twelve.) ‘He asked me to come and share his cheese,’ Sybille continues. ‘When— when I said no—when I said that eating cheese would be wrong—’

‘He called us heretics!’ Berthe wails. ‘He threw a stone at us!’

Sighs and grunts. Navarre purses her lips and shakes her head. Dulcie says, ‘God forgive the wicked.’

Gran farts.

‘This would never have happened in Laurac or Castelnaudary,’ Navarre growls. (Here we go again.

In Laurac the people had proper respect for us ...

) ‘In Laurac the people had proper respect for us. They were all believers—they revered Good Christians like us. There are too many Roman priests in Toulouse. Too many followers of the Devil. This place is a sink of corruption.’