Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind (2 page)

Read Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind Online

Authors: Sarah Wildman

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Cultural Heritage, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Jewish

“We have always agreed that life is both grandiose and ridiculous,”

Karl wrote to his closest friend, Bruno Klein, an old Viennese schoolmate, in December 1979

.

“You have always been and still are the master of this concept and this inner certainty. You laugh at the grandiose, the tragic, the heroic, and in the ridiculousness of life, you see grandeur and tragedy and heroism.”

Karl’s flight from Vienna—at age twenty-six, six months after the Anschluss, when Hitler swept through the city to throbbing throngs of well-wishers, and Jewish students were expelled from schools across the city, their families banished from work in hospitals, shops, parks, daily life, their world upended—was always described to me in similar grand terms—danger, excitement, fulfillment—nothing short of remarkable. Because he actually finished his medical degree before Jews were stripped of the right to finish school; because he got out at all. And it was complete with a happily-ever-after ending: the entire family, or at least the core of the group, the

essentials

, got out safely. The story of that escape—and the way I understood it—shaped my childhood imaginings, my nightmares, my dreams. The reality of that escape shaped his worldview.

To the same Bruno he wrote in 1983,

“Atheism is utterly incomprehensible to me. It is such a dry, cynical, uninformed, unfeeling and myopic mind that cannot see and feel and imagine the ‘beyond oneself.’ The energy, the majesty that profuses the cosmos . . . the exhilaration, the joy of life, the infinite of love, call it what you will. Why not God?”

This was very my grandfather. Everything was

herrlich

,

wonderful. Superb. Sublime. He was prone to bold pronouncements, would stand up at family events and command attention with philosophical meanderings. He was a bit prideful, a bit critical, entirely absorbed in the idea of the Jew in History, and where he himself fit into that. I still have my bat mitzvah letter from him, welcoming me to Jewish adulthood.

“As you grow and develop and encounter the world at an ever more meaningful and potent level, your awareness of this endowment will inform you, inspire you, and guide you.”

He closed with

Hazak v’ematz

—“Be strong and of good courage,” the words that Moses says to Joshua—“Be not afraid!”—when he realizes it will be Joshua who leads the Jews into the Promised Land and Moses will be left behind.

His relationship to Judaism was as much practical—he had his seat in synagogue, in the second row, he held court at Seder—as it was intellectual, philosophical, a game of minds and text study. To Bruno he wrote,

“It is the talent and the destiny of the Jew to have felt and known that there is a beyond, to have pursued it as an idea and principle. . . . The very name Israel is derived from the encounter of Jacob with an angel, a messenger of God. It means to have fought with God and to have prevailed.”

To have prevailed! It spoke to the essence of his escape, not to mention his confidence.

It was some years after his death when my grandmother casually told me that she had destroyed my grandfather’s personal correspondence. We were setting the table for dinner. “They sat in a filing cabinet for sixty-something years,” she said. “I decided that was long enough.” We fought about it. “They are all in German,” she said quietly, derisively. But though I hissed petulantly,

“It’s not a dead language,”

really, what was the point? There was no undoing.

“I saved the important things,” she said, slyly. “Like our love letters.” Emphasis on

our.

What was destroyed? I asked.

“Oh, I don’t know. Letters from Shanghai. People you’ve never met. People who are gone.”

Shanghai? People who are gone? It was tantalizing, infuriating. And over time it became clear that the point of her purge was, consciously or not, to preserve the myth of the spotless escape; and, in part, a carefully curated history.

I’m getting ahead of myself.

A few years after our argument, my grandmother was not well. She sat in my grandfather’s old home office, her movements manipulated by some terrible sort of Parkinson’s-like disease, as I rooted around in cabinets asking questions about random artifacts. She had always been so meticulous, in her appearance, in her demeanor; the last few years of her life were a blow to that—though there were some constants. She still perfumed herself with Emeraude, a scent that had remained unchanged—like her—since the 1920s; still wore her deep pink and coral lipsticks, still pushed herself into punishing girdles and stockings and heels, her Achilles tendons shortened by decades propped up on wedges. And she hadn’t changed the office, or the house, at all since his death, as though she—as though we—believed my grandfather would walk back in at any moment, sit down at his enormous walnut desk, and slice through the mail of the day with the long, sharp letter opener he kept for just that purpose. His marble busts of Schiller and Goethe, of Chaim Weizmann, the first president of Israel, and Theodor Herzl still sat in one windowsill; on the other side of the room, a black marble Apollo flexed his muscles into eternity. Volumes of literature in German lined the shelves. The deep teal blue and green armchair where he pierced my ears with a needle—at the age of five—was still placed exactly where it always sat, beneath a copper flying-saucer-like pendant light. A midcentury Danish daybed, dressed in green and blue wool, hugged the wall; I occasionally slept on it when I would come to visit.

That afternoon, in the cabinets beneath the bay windows where Goethe sat, staring, I came across an old album, the kind with black

pages and photo corners cradling black-and-white snapshots with scalloped edges. The photographs ranged from formal—stiff family portraits from the 1910s to the 1930s—to informal—crowds of laughing European teens and twentysomethings in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

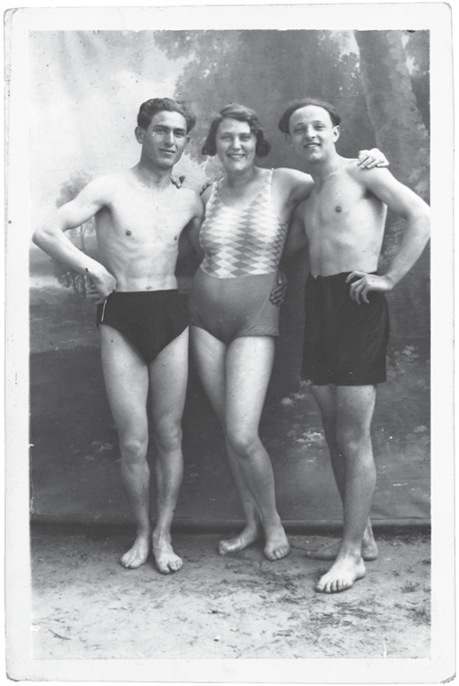

July 1929. On the left, Carl Feldschuh, my grandfather’s brother-in-law; on the right, Karl Wildman; the girl in the middle is a friend.

There was countryside and friends, attractive girls in old-fashioned swimming costumes, and a cheerful, muscular, incomprehensibly young version of the man I’d known as my grandfather, surrounded in one photo by a dozen girls, the literal focal point, the center of attention.

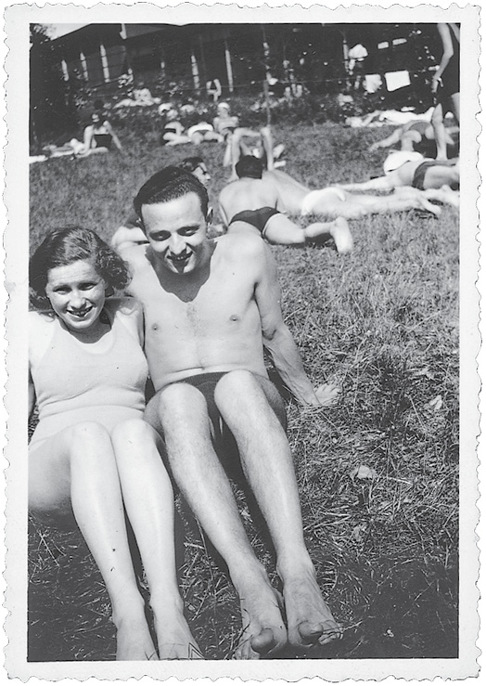

Among these images were dozens of tiny photos of a young woman.

“Your Valy”

was written on the back of each one, in a feminine hand I didn’t recognize. Here she was, laughing, rolling in the grass in Vienna’s Augarten—next to my grandfather. Here she was mugging, posed, hands on hips. Another showed the two of them lying on a bed, smiling coyly; it was shot into a mirror. There were photos of him and her in bathing suits, the two of them snuggled up close, laughing. They appeared, in the parlance of teenagers, to be more than friends.

How had I never seen this album before,

I wondered, turning the pages, trying not to let the paper crumble. This was his life, I realized, before any of us, before, even, my grandmother. And it was a life so—was there any other word for it?—

carefree

. They look so happy, so young, so fresh in the images dated 1932, 1934, 1935. This was his European life, the life—the people, the experiences—he had left behind.

Tucked into the back of the album, folded into a small, tight square, was a piece of paper pasted with a series of photos the girl named Valy had taken of herself. Each square was numbered, 1 through 4.

“I am so sad

,

”

says the first

(they are all written in German).

“I’m still waiting, but no letter from Karl has come yet!”

Here she makes a serious face. Then in square 2—“

Maybe this will help: ‘. . . If not, then not’”

—a photo, a wistful face (she is, I learn later, quoting from a popular song of the turn of the last century, “Der Eine Allein”).

Square 3: “

But no, it would be so much nicer if he’d write again, the way he used to, the way I endlessly long for it to be! If only he’d write again at last.”

Her gaze is now turned away from the camera, into the middle distance. By the fourth image she has turned again to her viewer, with a big smile:

“But maybe a letter will come tomorrow! One will surely come, won’t it?!”