Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind (51 page)

Read Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind Online

Authors: Sarah Wildman

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Cultural Heritage, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Jewish

Manele’s file was among those that were found by the Viennese Jewish community—the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde Wien, or IKG—at the turn of this millennium: a collection of hundreds of thousands of pages, a strange, dusty, moldy assemblage of notes, abandoned and forgotten, in a downtown Vienna attic—desperate requests to get out of the trap that Vienna had become, official questionnaires

filled out by frantic would-be émigrés, looking for exit visas and for financial assistance to leave. For over ten years, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, with the Jewish community of Vienna, worked to organize, preserve, and microfilm the material. In the summer of 2012, I was finally able to peer inside the holdings in the Austrian Jewish Archives and inquire what they had for the Wildmann family. Sure enough, there is a clear request filled out, stamped September 5, 1939, from Manele, almost exactly one year to the day after my grandfather left for New York.

Manele, I see, when I go over the file at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum with the help of an Austrian-American researcher named Anatol Steck, was a grocer, a merchant. Some months later I will go to visit the home address he lists on his questionnaire. The apartment is in the heart of Vienna’s posh first district, in a massive, dove-white marble building, carved with cherubs; the shop itself is nearby, on Bäckerstrasse. The grocery is now a mountaineering shop. Across the way is the Kaffee Alt Wien, which opened in 1936 as a coffeehouse. These days it is dark and smoky, with red banquettes, the walls plastered over with posters advertising past music concerts; it’s a scene of cheap beers and a crowd of late-night drinkers (it stays open well into the wee hours of the morning)—but when Manele ran his shop across the street, the deep wood of the bar would have been for

ein grosser Brauner

—a large espresso—and he would have had the chance to drink there, each morning, until Jews were forbidden to enter Aryan establishments.

The IKG file makes very clear what would have happened to my grandfather had he not fled when he did:

M

ANELE

W

ILDMANN

#38,016

Did you learn a new trade?

No.

Do you speak other languages?

German and some Hebrew.

What is your current economic position and income?

Not good. I’m destitute.

Are you in a position to get all the necessary documents for the emigration?

Yes.

Where do you want to go?

To Palestine.

What means do you have to facilitate your immigration?

Keine Mittel. [No means at all.]

What relationships do you have abroad, especially in the country where you want to emigrate to?

Ephraim Wildman, living in Petach Tikva. Son. Working in gastronomy—a restaurant— Worked at an orange plantation since 1932.

Do you have a valid passport:

No.

Relatives?

Daughter: Lotte Wildmann born in Vienna; profession Sales.

Blanka born in Vienna; also in Sales.

Then there is Josef Moses Wildmann born in Vienna, cobbler.

Wife: Chaja Sarah Wildmann. Housewife.

In his own words he continues:

I have a son in Petach Tikva who has written me that he has applied for me as well as my wife and my fourteen-year-old son to come; he believes that in October he will get the permission. But considering the fact I also have two daughters age 18 and 20 whom he cannot apply for, I am now forced to approach to ask the help and advice of the emigration department and then . . . as I’m asking the emigration department for their advice because it would only be an option if we could all go together and then my son can help us with advice and action.

I had on Bäckerstrasse a small grocery store. And that helped us to basically feed ourselves . . . but now we are able to feed ourselves only barely with a lot of distress. I have nothing to sell. I do not know whether there will be any income that might be used for the passage. We are living off our own provisions.

On the next page it is decided: Manele and Chaja have elected to send their young son, but they will not go with him.

Name:

Josef Moses Wildmann

Number of persons to destination:

One person to Palestine. One ticket from Vienna to Palestine

Money provided by applicant:

Zero

Still to be provided:

Zero

Current living conditions:

one room, one cabinet, one kitchen. Living room bedroom and a kitchen.

“That is where the whole family is living for 33 Reichsmark per month. That’s the rent. It says they have sublet part of it,” says Anatol, who is reading to me from the document.

Family relationships:

To remain behind: the parents and one sister.

Paid by:

Hachshara Mizrachi

Notes by the community:

[Josef] Has an elementary and basic schooling Hauptschule [trade school] and then Gymnasium. He has not earned a living yet. Father of the applicant had a small grocery store until October 23, 1938. The store was closed due to lack of stock/produce. They ate it all. The father of the applicant receives 15 m every month from the Jewish community in support and receives food from the soup kitchen for the last 8 months

6 September 1939

He [Josef] has luggage, and one bicycle.

Connections to abroad: Certificate comes from the brother.

The Jewish community interviewer of the Wildmann family—who it so happened was the same Wilhelm Reisz who commits suicide in Doron Rabinovici’s book—then adds an aside:

Information supplied is believable. Applicant makes a good impression. The need and the precarious situation are established by the above information. Approved 6 September 1939.

All this means, I realize: Manele and his wife, Chaja, believed they would be able to leave, but they would have only been able to take with them Josef, the youngest one. “He was applying to the immigration department for the whole family to travel together,” says Anatol. But in the end only Josef was sent to Palestine, alone. The girls, too, eventually fled. But their parents were, by then, stuck. “Often the older generation was left behind,” he explains.

My grandfather probably never knew exactly what happened to his half brother and his wife. But I do: in the last few years, all of the Gestapo files of Vienna have been scanned and placed online.

Manele and Chaja were arrested on the thirtieth and thirty-first of July 1941. In the end, they were not even granted the dignity of dying together: Manele was sent to Auschwitz, where he died in November; Chaja to Ravensbrück, where she lived until the following June. Their Gestapo files, and mug shots, are on files placed online by the DÖW—the Documentation Centre of Austrian Resistance. They look ravaged, worn, far older than their years; a long metal pole holds their heads up, like specimens. Chaja’s hair is messy, undone from her bun. Manele’s face looks bewildered, shot with exhaustion. Their life until deportation would have been complete misery.

For his part, in 1950, Karl went to Vienna to see what—who—was left. The city was still digging out from war destruction. Did he look for Valy on that trip? I have no notes, I have no messages from him to say what he did or with whom he met, or even what his impressions were of the city he had left behind twelve years earlier. I only know that he then went to Israel and met the surviving cousins. Of that leg of the journey, I have photos; Israel looks dusty and hot; large areas of land I know now as suburbs of Tel Aviv look expansive, unbuilt.

He began to patch up old relationships, reconnect with childhood friends. By this point, he had become the successful doctor Valy had believed him to be in 1941; by 1946 and 1950, he was flush enough to be able to give out small loans and donations to relatives—including money to Josef Wildmann, the son of Manele, who was still living in Tel Aviv. Affidavits were sent from one side of the globe to the other. There was contrition, there was redemption, there was, if not forgiveness, some resolution.

It must have taken some time. There are many letters that are so angry, so bruised by what the writers have been through, that they lash out at my grandfather for having the temerity not to have experienced it beyond 1938. And they are still—unlike the letters that come later—they are still talking about the war, what they lost. It is unfair to be angry with Karl, of course, and yet what has been fair for them? And yet still, as much as I scan, no one can tell me if they have heard news of Valy or her mother.

Tel Aviv, II/XII/1950

My very dear Karl:

Finally, after waiting for such a long time, I got your letter. You are making us wait too long. I was sure that you had forgotten about us. In German one would say “Out of sight, out of heart.” It has been four months. . . . I was very angry with you because you were so close to me, not just like a cousin, but more like a brother. As you know well, only little remained of our entire family. Our greatest joy is to know that somewhere, far away, on the other side of the ocean, there are close relatives of ours who show keen interest in what remains of the former large family. . . . Oh, how nice it would be to have you nearby in Palestine. That would be our greatest happiness. My advice would be to everyone to sell and liquidate everything and come to Ha’Eretz, because Israel is the only right place for Jews. . . .

You are not mentioning anything about dear Uncle Sam and the cousins. Are they not interested in being in touch with us by letter, or do they not recognize us as relatives? After Hitler’s war, the entire Jewish world was trembling, and everybody was looking for relatives and friends. Everybody wanted to know whether they were still alive, whether they needed anything. We are not so lucky to have relatives and close acquaintances who take an interest in how we are living; they are our cousins, and that is very sad. As God is our Witness,—we are not looking for any kind of [financial] support but rather contact by letter with our own family.

The writer is cousin

Reuven Ben-Shem (born Feldschuh; Ben-Shem was a zionification of his name). As a student in the 1920s, Reuven lived with my grandfather in Vienna and studied psychology with Freud. He had spent several years in Palestine, where he had been a founder of the Kibbutz Kiryat Anavim, outside Jerusalem. He returned to Europe in the early 1920s, when he received word his father had been murdered in a Ukrainian pogrom.

My grandfather was twelve years Reuven’s junior, also orphaned, and they were very close. Reuven went on to work in Poland—as a journalist, as a writer, as an editor. He married a musicologist named Pnina, and together they had a daughter named Josima, who was a piano prodigy. Pnina encouraged them to stay in Poland, even after the Germans invaded.

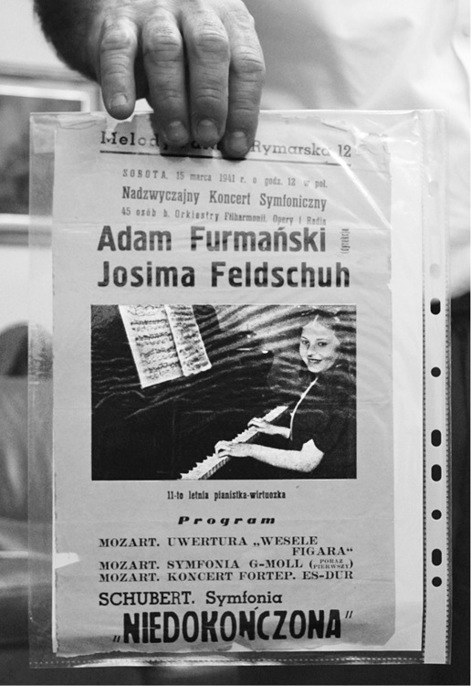

Late on a Friday night in the Tel Aviv suburb of Ramat Gan, a few days after I met Gilbert Sudarskis, I find myself at a Shabbat dinner with Reuven’s family. The guests have moved from the table to a sagging leather couch, an array of liquor lined up on the coffee table. Our host, Kami Ben-Shem, Reuven’s son born after the war to his second wife, goes into a backroom and brings out a selection of crumbling yellow paper. The first page, which is kept in a plastic sleeve, is an announcement for a concert. It is dated at the top “15 March 1941”; “Josima Feldschuh,” it says, above the image of a rosy-cheeked girl with a bow in her hair, sitting at a piano, and then, below her photo,

in Polish, “11 year old piano virtuoso.” The program promises selections from Mozart’s

Marriage of Figaro

and Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony, a concert held at Rymarska 12, in the heart of the Warsaw Ghetto.