Parallel Myths (3 page)

Authors: J.F. Bierlein

Such gods were personifications, and yet they were viewed as real spiritual forces that had to be worshiped, implored, and appeased. This use of personification tells a great deal about the cultures in which it was common.

The Greek myth of Cupid and Psyche is, on the surface, a charming love story with a moral. But it makes a great deal more sense when it is understood that the names of the characters have meanings. Cupid is the Roman name for the Greek god of love, Eros;

eros

means “sexual love” in Greek.

Psyche

means both “soul” and “butterfly” in Greek. Therefore, this myth is a statement on the relationship between physical love and soul love, wherein the soul, like a butterfly, undergoes a metamorphosis.

Throughout the myths given here, we shall see many examples of this use of language. Often I have seen myths presented without an explanation of the meanings of the names. Although entertaining, such tellings of the myth give the reader a one-dimensional view.

Language is everything to myth. The spoken word has great power. It is through the spoken word that God creates the world in Genesis.

In the Talmudic story of Creation, the letters of the Hebrew alphabet compete to be the first letter of the first word spoken by God in the Creation. In Persian mythology, it is the utterance of only one word by Ahura Mazda (the Good God) that casts Ahriman (the Bad God) into hell. The name of God is still so sacred to the Jews that to pronounce it is to profane it.

The use of sacred languages is also a means to separate what is sacred from that which is profane

(profane

is used here to mean “common,” “ordinary,” “everyday”). The Latin mass, persisting in places to the present day, signified the unity of the Roman Catholic church in that the same words were spoken at every mass throughout the world, in a sacred language separate from the vernacular. The Orthodox Christian churches in many Eastern European countries use a language called “Old Church Slavonic,” a now obsolete tongue, as the language of the liturgy. Modern Jews who speak Russian or English or French still pray in Hebrew,

ha loshen ha kodesh

*

the “sacred” language. Muslims in England and Indonesia recite the Koran in Arabic, believed to be the language in which God spoke to Muhammad; few of these people may otherwise speak Arabic.

The German scholar Ernst Cassirer, in his book

Language and Myth

, sees language as an indication of religious development. In the earliest phases of religion, the so-called primitive stage, there is the undifferentiated concept of “powers that be” that must be reckoned with or appeased. At a later stage, the stage of polytheism (from the Greek for “many gods”), there is personification of the gods by function, or an object such as the sun is personified. In this stage, the corn goddess must be well treated to ensure a good crop.

Cassirer then points out that reflection upon religious questions, and the earliest phases of philosophical speculation, brings a sense of monotheism (Greek for “one god”), a single deity that is behind all phenomena. This deity at first may be appeased as were the earlier gods. However, even this gives way as the relationship with the god

or God becomes subjective and self-contained, rather than one in which forces are external, discrete dispensers of cosmic good or ill. It is at this stage that one seeks a “union” or “personal relationship” with God, internally communicating more easily with one God than with many. The Hindus speak of Brahman, the Supreme Being, as “the Great Self.” The Christian speaks of the “heart” as the dwelling place of the Holy Spirit of God. In this stage, the deity is a subject that dwells

within

the individual.

Have you ever wondered why there are 365 days in a year? Of course, the obvious answer is that this is the time that it takes for the earth to revolve around the sun—the solar year. However, why is our calendar based on the solar, and not the lunar, year?

We received our calendar pretty much intact from the ancient Romans, who, in turn, believed that the Egyptians were the best astronomers in the world. According to Sir James G. Frazer, author of

The Golden Bough

, one of the pioneer works analyzing myth, the 365-day year has its origins in an Egyptian myth.

The Egyptian god Osiris, later the god of the dead, was the offspring of the illicit union of the earth god Geb and the sky goddess Nut (the ubiquitous Egyptian obelisks, such as London’s Cleopatra’s Needle, are phallic representations of Geb touching Nut). Nut was technically the wife of Ra, the sun-god, who was not at all amused to learn of his wife’s pregnancy by another god.

To express his displeasure, Ra ordained that the child of this affair would be born in “no month and no year.” Now, the promiscuous goddess Nut had yet another lover, Thoth, the god of wisdom. Nut explained her predicament to Thoth, who always had an answer for everything. Thoth challenged the moon to a game of backgammon. Because the moon was then the regulator of time, the Egyptian year consisted of thirteen lunar months of thirty days each, or 360 days. Thoth won one seventy-second part of every day from the moon, which together made five whole days. These days fell between the

end of the last month and the beginning of the first month of the lunar year. Thus, these five days were in “no month and no year.” Osiris was born during this five-day period, fulfilling the prophecy of Ra, the jealous husband, and reconciling the lunar year of 360 days with the solar year of 365.

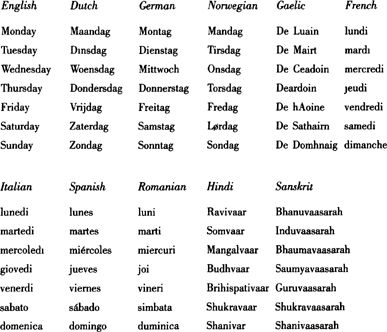

The days of the week in the Germanic, Celtic, Indian, and Romance languages (with the exception of Portuguese) are based on mythology.

Derivations

MONDAY

—The moon’s day.

TUESDAY

—The day sacred to the Germanic war god Tir or Tiw; the day sacred to the Roman war god Mars.

WEDNESDAY

—The day sacred to the Germanic chief god Wotan or Odin; the day sacred to Mercury, as in the unmistakable Romanian word

miercuri

.

THURSDAY

—The day sacred to the god who dispenses thunderbolts, the Germanic Thor and the Roman Jupiter or Jove.

FRIDAY

—The day sacred to the goddess of beauty, the Germanic Frigga or Freya.

SATURDAY

—From the god Saturn, a predecessor of the Olympian gods. Sábado, etc., come from the Hebrew

Shabbat

, the English

sabbath

.

SUNDAY

—The day sacred to the sun. In the Romance languages and Gaelic, it comes from the Latin

dominus

, meaning “Lord,” hence “the Lord’s day.”

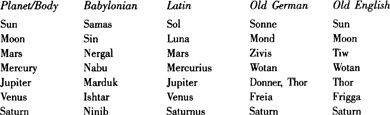

As if that weren’t easy enough, the days of the week are all named in honor of a heavenly body identified with a god, a lineage that can be traced back to ancient Babylonia

*

:

It is interesting to see the consistent parallel: Ishtar, Venus, and Frigga were all goddesses of beauty in their respective cultures. Marduk,

Thor, and Jupiter were representatives of a younger generation of gods, as well as the dispensers of thunderbolts. Interestingly, both Marduk and Jupiter became chief gods by overthrowing an earlier deity.

The months, likewise, have a largely classical origin. Months, of course, are reckoned by the moon. The “many moons” of the American Indians in Westerns is actually the same as “many months,” as our English word

month

is derived from

moon

.

Derivations

JANUARY

—From Janus, the two-faced Roman god of the gates who faced backward and forward.

FEBRUARY

—From the Latin

februare

, meaning “to purify.”

MARCH

—From Mars, the Roman god of war.

APRIL

—From the Latin

aprire

, meaning “to open;” this is the month that flower buds begin to open.

MAY

—From the Latin month sacred to older men or

maiores

. It was also sacred to the Roman goddess Flora, whose name means “flower.” The custom of the maypole is certainly the continuance of a fertility ceremony, complete with phallic symbol.

JUNE

—Either from Juno, goddess of childbirth and wife of Jupiter, or from the month sacred to young men,

juniores

.

JULY

—From the deified Roman Julius Caesar.

AUGUST

—From the deified Emperor Augustus.

SEPTEMBER

—From

septem

, or “seven.”

OCTOBER

—From

octo

, or “eight.”

NOVEMBER

—From

novem

, or “nine.”

DECEMBER

—From

decem

, or “ten.”

The very manner in which we reckon years, keeping track of our history, is based on myth and religion. Let’s take a random year, 1993. This may well be read as “In the year of Our Lord (Jesus Christ) 1993.”

*

Non-Christians use the term C.E., or Common Era, a concession to the Christian system of dating. This mythological origin

of dating is common throughout the world. In Japan, the traditional calendar begins with the mythical beginning of the reign of the first emperor, Jimmu, descendant of the sun-goddess Amaterasu. The Romans began their dates with the mythical founding of Rome by the twins Romulus and Remus in 754

B.C

. (by our system of dating), and further subdivided dates according to the reigns of emperors. The Islamic world begins its calendar with the Hegira, the flight of Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina in

A.D.

622.

Myth paints the milestones by which we reckon time.

Sacred Time

This is the authentic content of the Doctrine of Eternal Recurrence: that eternity is the Now, that the moment is not just the futile now, which is only for the onlooker, but the clash of a past and a future.

—Martin Heidegger (1889-1976)

The heterogeneousness of time, its division into “sacred” and “profane,” does not merely mean periodic “incisions” made in the profane duration to allow of the insertion of sacred time; it implies further that these insertions of sacred time are linked together so that one might see them as constituting another duration with its own continuity…. A ritual does not merely repeat the ritual that came before it … but is linked to it and continues it, whether at fixed periods or otherwise.

—Mircea Eliade (1907-1986)

Sacred time is a separate time for a separate reality that transcends clock, watch, and calendar, for it marks our appointments with the Eternal.

In reading myths and in practicing our religions, we make an almost unconscious distinction that separates time into “sacred” and “profane.” “Profane” time is wristwatch and calendar time. Sacred time, however, is exemplified by the Christian Eucharist, the taking of consecrated bread and wine; when Christians observe it, it is a direct connection with the original Seder meal celebrated by Jesus and his disciples. For Catholic, Lutheran, Anglican, and Orthodox Christians,

Jesus is believed to be present at each Eucharist. For most Protestant Christians, it is the continuation of a memorial of that meal. Each celebration of the mass on any given Sunday in Christendom is connected with the mass before it, all the way back to that Passover meal in Palestine two thousand years ago. That connection, the sense of timelessness within time, is an illustration of sacred time.

The Jewish Sabbath is perhaps the demonstration of sacred time that is most familiar to us. The Sabbath recalls the “time before time” and was instituted when God rested from the work of creation. The first humans lived in Paradise

(Gan Eden

, in Hebrew) and there was neither sin, work, nor fear. The devout Jew speaks of the righteous spending the afterlife in

Gan Eden

. A very famous Jew, Jesus Christ, told the thief on the cross next to his, “Today you will be with me in Paradise.” The Messianic age, when the Jewish people will see the arrival of a Messiah, is spoken of as a re-creation of

Gan Eden

at the end of history. From the earliest past, one has a sense of what Paradise was like and the hope that it will return; the Sabbath is a little taste of

Gan Eden

in the here and now.