Paul Revere's Ride (36 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

William Emerson, the highly respected minister of Concord, was a militant Whig who stiffened the resolve of his town. This wax portrait is in the Concord Free Public Library

“Who

is

this man?” the Loyalist asked imperiously.

“Hosmer, a mechanic,” Bliss replied.

“Then how comes he to speak such pure English?”

“Because he has an old mother who sits in the chimney corner and reads English poetry all the day long, and I suppose it is like mother, like son.’ He is the most dangerous man in Concord. His influence over the young men is wonderful, and where he leads they will be sure to follow.”

13

On April 19, Lieutenant Hosmer and his radical young friends spoke out for strong measures. Colonel Barrett and his kin were voices of restraint.

The British drums were coming closer, but still the townsmen continued their debate. The men of Lincoln arrived, and joined in. One gestured toward the oncoming Regulars and said, “Let us go and meet them.” Eleazer Brooks of Lincoln answered, “No, it will not do for us to begin the war.”

14

The drums were now very near. Once again the “more prudent” men repeated that it would be “best to retreat till our strength should be equal to the enemy’s.” Prudence prevailed. It was agreed to abandon the village to the advancing British force. The militia, still heavily outnumbered, retreated north to the next hill. To avoid an incident Colonel Barrett took them across the North Bridge, all the way to Punkatasset Hill, nearly a mile from the town center but overlooking it across the open country.

15

Colonel Smith led his Regulars into an undefended village. No men of military age remained to oppose him—only women and children and old men. The people of the town had heard the news of Lexington (some of it at least), and they were angry. Two British officers described them as “sulky” and “surly.” One infuriated elder attacked Major Pitcairn with his fists.

The British soldiers responded with restraint. Colonel Smith strictly enforced General Gage’s orders that the people of Concord were to be treated correctly, and that private property was to be respected. Even so, there was a little looting. One soldier amazed the town by stealing a Bible from the meetinghouse. Another helped himself to a volume appropriately titled

Liberty of the Will.

Their officers permitted one act of political destruction: the town’s liberty pole was cut down and burned. Otherwise, the troops remained on their best behavior.

16

The Regulars went speedily about their business. General Gage’s elaborate orders were followed to the letter. Both bridges

into town were quickly secured. A single company of light infantry was thought sufficient to hold the South Bridge. A larger force, seven companies of light infantry, went to the North Bridge where the men of Concord had retreated. Four of those seven companies were sent on yet another long march, two miles beyond the North Bridge, to Colonel Barrett’s house and mill, which Tories had reported to hold a great store of munitions. Two companies from the 4th and 10th Foot were ordered to hold the high ground along their route, and a company of the 43rd Foot guarded the bridge itself.

17

The grenadiers remained in Concord center. Their assignment was to search the village, and to destroy any materials of war they found there. All morning they toiled at that thankless task. They worked systematically through the village, entering without warrant the houses that had been reported by General Gage’s spies. No resistance was offered except at the tavern of Ephraim Jones, an innkeeper of outspoken Whig principles who doubled as the town’s jailor. Major Pitcairn went directly to the inn and banged on the door. Jones defiantly refused to open it. A party of grenadiers broke it down. Pitcairn rushed inside, and hard words were exchanged. The angry Marine knocked the infuriated innkeeper to the ground, “clapped a pistol to his head,” and threatened to use it unless information was forthcoming. At pistol-point, Jones led them to three large 24-pounder cannon, buried in his yard. Next door, a Tory was found languishing in the town jail, and speedily set free. Major Pitcairn then released his captive, and surprised him by offering to buy a breakfast for his men, and insisted on paying the bill.

18

Aside from the three cannon, not much was turned up in the way of munitions. Paul Revere’s repeated warnings had achieved their purpose. Many things of military value had been spirited away in the busy weeks since he had ridden to the town. The English Whig historian George Otto Trevelyan wrote contemptuously that the grenadiers “spoiled some flour, knocked the trunnions off three iron guns, burned a heap of wooden spoons and trenchers, and cut down a liberty pole.”

19

A cache of lead bullets was also uncovered and tossed into the millpond, from which it would be salvaged the next day. Some of the British Regulars made a pyre of wooden gun carriages, and set it ablaze. The fire spread quickly to the town house and threatened to destroy it. For a moment, in this strange semi-civil war, the soldiers and the townspeople forgot their differences and joined

together in a bucket brigade to save the building. The gun carriages continued to burn, sending a cloud of smoke billowing high above the village.

Beyond the North Bridge, four companies of light Infantry marched to Colonel Barrett’s house and mill, which only a few weeks earlier had indeed been an important arsenal. But since April 7, when Paul Revere carried his first warning to Concord, the town had been hard at work, moving military supplies to safety. Much material had been sent to Sudbury, Stow, and other places. What remained was hidden with high cunning. At the last minute, Colonel Barrett’s sons plowed a field on his farm, planted weapons in the fresh furrows, and covered them over again. The British soldiers passed by without a second thought, little suspecting the crop that had been sown there. British Ensign De Berniere wrote in frustration “We did not find so much as we expected.” In fact they found scarcely anything at all.

20

The British troops took their time at Barrett’s house. After the long night march they were tired and hungry, and several demanded breakfast from Mrs. Barrett. She gave them food and drink, saying coldly, “We are commanded to feed our enemy if he hunger.” They offered to pay. When she refused, the soldiers tossed a few shillings into her lap. She told them, “This is the price of blood.”

21

At the North Bridge, the British companies awaited the return of their comrades, and guarded the line of their retreat. To the north, the men of Concord were gathering their strength on Punkatasset Hill as reinforcements came flowing in from surrounding towns. Hovering around them was a crowd of women, children, and dogs. Several soldiers led the noncombatants to a place of safety and tried in vain to shoo the dogs away, at some cost to military dignity.

22

The militia consulted yet again, and decided to move closer. They marched south about 1000 yards from Punkatasset Hill to their muster field, a flat hilltop about 300 yards northwest of the bridge.

23

A company of British light infantry had occupied this high ground; but as the militia advanced, the Regulars retreated down the hill toward the bridge. The New England men and the British troops eyed each other warily, a few hundred yards apart.

Among the militia was an English immigrant named James Nichols, who had become a farmer in Lincoln. He was much liked by his American neighbors, who found him a “good droll fellow and a fine singer.” Nichols was uneasy at the prospect of fighting

the King’s troops, more so than the Yankees who surrounded him. He stood quietly for a while, watching the Regulars, then turned to the men in his company and said, “If any of you will hold my gun, I will go down and talk to them.” He walked down the hill, and chatted with the Regulars for a moment. Then he came back, retrieved his gun and announced that he was going home.

24

While Nichols departed, many other men arrived from nearby towns. Parts of two New England regiments were now in the field. Concord’s Major John Buttrick led the local regiment of Middlesex minutemen, of which five full companies were now assembled from Acton, Bedford, Lincoln, and two from Concord. Beside them stood Colonel James Barrett’s regiment of Middlesex militia, five companies of older men from the same towns. Other men were streaming in from Carlisle, Chelmsford, Groton, Littleton, Stow, and Westford, west and north of Concord. Altogether, about 500 armed men were in the field.

25

The senior officer present was Colonel Barrett, who took command of the entire force, supported by Major Buttrick. As a gesture of unity to the young men, Lieutenant Joseph Hosmer was invited to join them as adjutant. None of these officers was in uniform. Colonel Barrett was dressed in “an old coat, a flapped hat, and a leather apron.” Hosmer commonly wore a homespun suit of butternut brown. These Concord leaders did not make an elegant appearance, but they understood their duty and had the confidence of their men.

26

Colonel Barrett ordered the two regiments into a long line facing the bridge and the town, which was clearly in view across the open ground. The officers and men consulted together yet again. They were uncertain what to do. Then suddenly they began to notice smoke rising from the village. Young Lieutenant Joseph Hosmer turned to Colonel Barrett and asked boldly, “Will you let them burn the town down?”

27

In any professional army, no lieutenant who valued his career would dare speak to his colonel that way. But this was the New England militia, and others joined in. Captain William Smith of Lincoln announced that he was prepared to drive the Regulars from the bridge. Captain Isaac Davis of Acton drew his sword and said, “I haven’t a man who is afraid to go.”

28

Colonel Barrett ordered the men to load their weapons. Many had done so already; some deliberately double-shotted their muskets. In his prudent manner, Barrett walked the ranks, speaking words of caution to his men. Several remembered his “strict orders” not to fire until the British fired first, but then “to fire as fast as we could.”

29

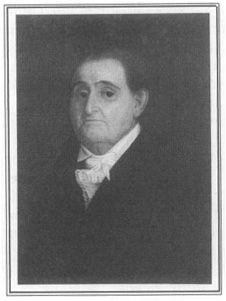

Joseph Hosmer was the outspoken Concord artisan who challenged his commander Colonel James Barrett to advance on the Regulars at North Bridge. His portrait is in the Concord Free Public Library

At Concord’s North Bridge and Lexington Green, the actions of New England’s military commanders were remarkably similar: to challenge the British force, but not to fire the first shot. It was agreed by these leaders that when the fighting began (most now believed it to be inevitable) the Regulars must start it. This strategy was adopted with surprising unanimity. Probably it was agreed in advance. Paul Revere’s many rides to Concord and Lexington were not merely for the purpose of reporting British movements, but also of concerting the American response. Early that morning, Lexington’s Captain Parker made sure that every private in his company understood this strategy. Concord’s Colonel Barrett did the same thing at the North Bridge.

Then Colonel Barrett gave the order to advance. The men moved forward from their right in double file. This was not a combat formation. It was perhaps Barrett’s hope to move across the bridge without engaging the Regulars, and to make a demonstration before the village.

Below them, the British soldiers were ordered to fall back across the bridge. Several began to pull up the wooden planking. At that sight, a wave of fury swept through the Concord ranks. Major John Buttrick shouted a warning to leave the bridge alone. This was

their

bridge! Buttrick’s home was just behind him. Standing

on his own land that had belonged to his family since 1638, he turned to his minutemen and said, “If we were all of his mind he would drive them away from the bridge, they should not tear that up.” Amos Barrett remembered, “We all said we would go.”

30

The New England men were thus consulted—not commanded—on the great question before them.

31

The two New England regiments moved down the hill in a long column, led by young fifer Luther Blanchard of Acton, who had marched onto the field playing a spirited march called “The White Cockade,” an old Jacobite song that was thought to be “intensely galling to the Hanoverians.” Acton’s minutemen were put in the van, because they were one of the few companies to be fully equipped with bayonets and cartridge boxes that allowed a greater rate of fire than powder horns. Behind the Acton company came the minutemen from other towns. The militia followed, and the alarm lists brought up the rear.

32

The Regulars by the bridge turned and looked up the hill in amazement at the men coming toward them. They never imagined that these “country people” would dare to march against the King’s troops in formation, and were astonished by their order and discipline. One British soldier wrote that the Yankee militia “advanced with the greatest regularity.” Another noted that “they moved down upon me in a seeming regular manner.” A third reported that “they began to march by divisions down upon us from their left in a very military manner.” Slowly the British Regulars began to understand that this was no rural rabble confronting them.

33