People of the Dark

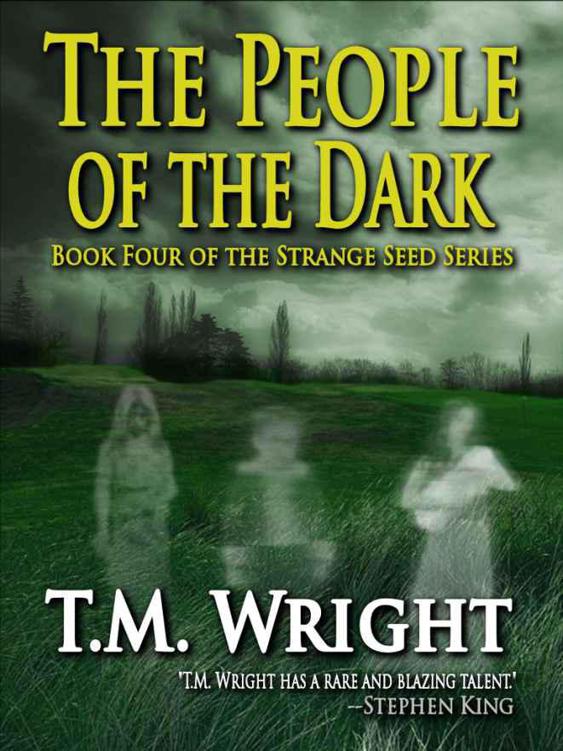

THE PEOPLE OF THE DARK

T.M. Wright

Digital Edition published by Crossroad Press

© 2012 / T.M. Wright

Copy-edited by: David Dodd

Cover Design By: David Dodd

Background Images provided by:

This eBook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only.

This eBook may not be re-sold or given away to other people.

If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with.

If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should return to the vendor of your choice and purchase your own copy.

Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

NOVELS:

The Strange Seed Series

STRANGE SEED

NURSERY TALE

THE PEOPLE OF THE DARK

THE LAUGHING MAN

The

Biergarten

Series

THE CHANGING

THE DEVOURING

GOODLOW'S GHOSTS

THE ASCENDING

SLEEPEASY

The Manhattan Ghost Story Series

THE WAITING ROOM

A SPIDER ON MY TONGUE

Standalone Novels

BOUNDARIES

NON FICTION:

THE INTELLIGENT MAN'S GUIDE TO U.F.O.s

UNABRIDGED AUDIOBOOKS:

A MANHATTAN GHOST STORY – NARRATED BY DICK HILL

THE CHANGING – NARRATED BY ANDREW RANDALL

Try any title from CROSSROAD PRESS — use the Coupon Code FIRSTBOOK for a one-time 20% savings!

We have a wide variety of eBook and Audiobook titles available.

Find us at:

http://store.crossroadpress.com

With love, for Chris

W

hen I was a boy of eleven or twelve I was walking alone at dusk through a heavily wooded park near my home. It was a park I'd walked through almost every evening on my way home from school and I felt at ease in it, even when the light was failing and the whisper of an evening chill was in the air. Above the hulking, dark and ragged line of the trees, the sky always had the pale yellow glow of the city splattered on it, and every now and then I could hear the blare of a car horn, or a dog barking, or, depending on if I was near the perimeter of the park, a family argument erupting out of nowhere. These were comforting sights and sounds because they told me that civilization was close by, that I was not alone, after all, though, if I wanted, I could

pretend

that I was alone. And that was something I pretended quite a lot. Because being alone, in the woods, in the dark, was spooky, and spooky was fun.

That's what I was doing that night when I was eleven or twelve, and coming home through the park at dusk. I was pretending that I was alone, that the park was a vast and uncorrupted wilderness, that there were no houses within shouting distance, and no city lights painting the dusk a grimy yellow. I was pretending that there were bears close by, and bobcats, foxes, moose, rattlesnakes. I was transporting myself to a place where the earth itself was not just many things—friend, enemy, mother—it was the only thing.

And on that particular early evening when I was eleven or twelve, I sat down in a clearing surrounded by evergreens and thickets to watch the night come. I remember I was hungry because the lunch that day in school had been something awful—peanut butter sandwiches on Wonder Bread, with carrot salad as a side dish—so I'd skipped it. And, as well, the beginnings of a cold were moving about in my blood. But I was something of a dreamer, and I was young, so there was very little that could stop me from doing what I wanted to do.

It was a Friday; I had that small and special kind of happiness that comes only to school kids on Fridays, when two whole days of freedom have opened up before them. And I remember that it was early in the school year, September, probably, because the evening was warm, and humid; I could hear mosquitoes whining in the air around me, and that got me to thinking that the bats soon would come to eat them. I didn't like bats, but the idea that soon they'd be silently scooping up their evening meal in the air above me gave me only a passing shiver.

That particular clearing was one I'd paused in a couple of dozen times before. It was rimmed by tall evergreens, a few venerable old maples, and one immense and dying oak whose branches already were nearly bare of leaves.

It was from behind the dark trunk of that oak—visible only as a patchy, black

presence

against the backdrop of gathering darkness—that a child appeared and swept toward me with his arms wide and, when he was only a couple of feet away, and I could see him more clearly, a look of immense desperation and pleading on his face. Then he was gone.

STRANGE SEED

R

ealization, like punishment, comes swiftly to the child. And, as to punishment, he winces and stifles a moan. Here, in the bright sunlight, denial is impossible. He sees that his father's body is becoming what swamps are made of, and soil is made of—becoming food for the horsetail, and clover, and burying beetles, and a million others. Because the earth, the breathing earth, must be constantly nourished.

His father's words are closer now, and understandable. "Decay is not the grim thing it appears to be. It is renewal."

"Father?" the child pleads, realizing the futility of the word. "Father?" he repeats, more in memory of those times his father responded to the word than for any other reason.

Father?

—distantly, from the thickets to the south.

Father?

Barely audible.

The child looks questioningly up from his father's body. "Father?" he calls.

Father?

An echo, the child thinks. Months before, he remembers, in the heart of the forest, "Hello," extended, "Hello," repeated, "Hello," shouted back at both of them, father and son, by the voices of the forest.

"Hello," the child calls.

Father?

replies the voice of the thickets.

"Hello," the child calls. And distantly, from the east, from the forest, "Hello, Hello, Hello," decreasing in intensity. And finally, nothing.

Hello

—from the thickets.

"Hello," the child calls.

Hello

.

"Hello, Father!" the child calls.

And the forest replies, "Hello, Father! Hello, Father!—

And the voice of the thickets replies,

Hello, Father! Father? Hello!

NURSERY TALE

T

he first three young couples in Granada—the

Meades

, the

McIntyres

, the

Wentises

—were very much of a type, it was true. Bright young suburbanites with a taste for getting ahead, who liked being looked upon as "special," but who tried, to varying degrees, to carry that perception of status with humility. They all gave generously to the proper charities, they all belonged to one of the two major political parties, the men all held white-collar jobs. Which is not to say that these couples were indistinguishable, one from another. . . .

The

McIntyres

, the

Meades

, and the

Wentises

came to Granada in pursuit of a dream. They believed what the brochure had told them about "open spaces and room to breathe—all within the framework of a secure, planned community" because that was what modern living was all about. It was their birthright, wasn't it, to seek out what was most comfortable, and easy.

That was the dream, after all.

And all of them were dreamers.

THE CHILDREN OF THE ISLAND

A

nd on the Upper West Side, in a law office on West 110th Street, the newly installed junior partner of the law firm of Johnson,

Bigny

and Belles, a young woman named Karen Gears looked up from her work at a window which faced south and one word escaped her, "No!" It was a plea, a word of desperation—keep the dreams away, lock them up in her childhood, where they belonged, where, indeed, they had begun, and where she had supposed they had ended. . . .

On the fringes of the West Village, in lower Manhattan, a good-looking, dark-haired, gray-eyed boy was lying on his back on his bed. The lights were out, the shades and curtains drawn. He had always liked darkness.

He was remembering that just two days before, he had somehow gotten Christine

Basile

, of all people, to agree to go out with him. He was remembering, also, that barely a month before, he'd celebrated a birthday. His sixteenth, he'd been told. The man who called himself his father had given him an extra set of keys to the car.

The boy was weeping now, and he was whispering to himself, "What a crock of shit, what a damned crock of shit!" . . .

In Manhattan, on West Tenth Street, in a small bachelor apartment which had been decorated very tastefully in earth tones, and included a wicker loveseat, bamboo shades, and a large, well-maintained freshwater aquarium, a man named Philip Case—who was apparently in his early thirties—was holding his head and tightly gritting his teeth, trying futilely to shut out the images that came to him in waves, like a tide filled with bad memories. . . .

There were a hundred or more Philip Cases in Manhattan that night. A hundred or more Karen Gears. A hundred or more boys lying in their darkened rooms and trying desperately to recall the events of just one or two days before. Because such events were their reality, and reality was rapidly slipping away from them. . . .

They had become what they had lived amongst. They had grown apart from the earth, because they had rarely touched it.

They had grown secure in what they'd become, and so had tossed aside what they had been. In stark desperation they had discarded it, and forgotten it. Because it was impossible to be both what they were, and what they had changed themselves into.