People of the Deer (3 page)

The Anson grumbled forward on her quest. Johnny held a map before him on his knees, and over its expanse of vagueness he had drawn a straight compass course to where Windy River should be. But above his head the compass flickered and gyrated foolishly, for in such close proximity to the magnetic pole a compass is, at best, but a doubtful tool. Yet there were no other aids to navigation, for when we left the coast we also left the sun behind usâobscured by a thick overcast of snow-laden clouds. And as for finding our way by the land underneath us...

It was a soft white nightmare that we were flying over. An undulating monotony of white that covered all shapes and all colors. The land, with its low sweeping hills, its lakes and its rivers, simply did not exist for our eyes. The anonymity was quite unbroken even by living things, for the few beasts that winter here are also white, and so they are no more than shadows on the snow.

For a hundred miles there was no change and the monotony began to dull my senses. Johnny passed his map back to me and along the course line he had drawn a cross and added a penciled notation. “Halfway. Should be there shortly after noon.”

I turned back to the window and tried to fix my gaze on something definite in the blankness that lay below. Then I glanced ahead and saw, with profound gratitude, the faint smear of a horizon. Slowly it took on strength, grew ragged, and at last emerged as a far-distant line of hills. It was the edge of the great plateau which cradles Nueltin, and the Kazan.

Now the white mantle below us began to grow threadbare. Black spines of massive ridges began to thrust upward through the snow. The undulations of the land grew steeper, as swells begin to lift before a rising storm at sea.

Again the map. This time the cross lay over Nueltin, but when I looked down I could see nothing recognizable to tie us to the map. I edged forward to the cockpit. Johnny's face was strained and anxious. In a few minutes he pointed to the flickering needles of the gasoline gauges which showed that half our gas was gone, and then I felt the aircraft begin to bank! I watched the compass card dance erratically until our course was south, then eastâand back toward the sea.

The limit of our search had been reached, and we had found nothing in that faceless wilderness to show us either where we were, or where our target lay. We had overleaped the boundaries of the Barrensâand yet the land had not been caught unaware. It still seemed secure against our invasion.

The overcast had been steadily lowering and as we turned eastward we were flying at less than five hundred feet. At this slim height we suddenly saw the land gape wide beneath us to expose a great valley walled in by rocky cliffs and snow-free hills. And in that instant I caught a fleeting glimpse of something... “Johnny!” I yelled. “Cabin... down there!”

He wasted no precious gas on a preliminary circuit. The sound of the engines dulled abruptly and we sank heavily between the valley walls. Before us stood a twisted, stunted little stand of spruce; a river mouth, still frozen; and the top foot or so of what was certainly a shanty roof, protruding slyly from the drifts.

We jumped stiffly down to the ice and shook hands, for there was no doubt about this being my destination. There was no other standing cabin within two hundred miles.

But only the wind met us. There was no sign of life about the cabin. We slipped and stumbled helplessly on the glare ice, and our exhilaration at having found our target against heavy odds was rapidly being diminished by an awareness of the ultimate desolation of this place. Our eyes clung hopefully to the handful of scrawny trees, none of them more than ten feet high, that thrust their tops out of the snow to give a ragged welcome. The leaden skies were closing in and the wind was still rising. There was no time to explore, only time to dump my gear onto the ice. Johnny stood for a long moment in the doorway of the plane, as if he was debating with himself whether to ask me if I had changed my mind. I'm glad that he didn't. I think I should have been tempted beyond my strength. But he only waved his hand and vanished into the fuselage. Then the Anson was bumping wickedly down the bay.

The plane vanished with appalling rapidity into the overcast. The gale from the Ghost Hills whipped little eddies of hard snow about me and I had arrived in the land that I had set my heart upon.

But now was no time to soliloquize! I needed shelter, and so I made for the half-hidden cabin. The doorway was snowed-in to a depth of several feet, and when I had dug my way through, I found only a log cavern in the driftsâdank and murky and foul-smelling. The damp was the stinking damp of long disuse, and I could trace the smell easily enough to the floor that was buried under the dirt of years and the accumulated refuse of a winter's meals.

Against one wall was a massive stove. But it did nothing to cheer me up, for as far as I could see there was no fuel for its great maw. The wind outside, and the chill damp inside, made the thought of a fire like the dream of a lovely womanâirresistible, and quite unattainable.

The walls of the cabin were finished in fur. Wolf and arctic fox pelts, all as white as the snows of early winter, were spread over the log walls to dry, and by their simple presence showed that the place was not completely deserted after all. During the next week I came to regard them with affection, for they were the link with the unknown man who had brought them in and who, I sincerely hoped, would come himself before too long.

There was quite enough to do during the days of waiting. All my gear had to be hauled in from the ice of Windy Bay, and for the balance of the daylight hours I amused myself by wading hip-deep, and sometimes shoulder-deep, through the jealous drifts that guarded the puny treelets near the camp. Three hours' hard work would yield only enough green spruce and tamarack twigs to let me build one little cooking fire, but in the process of gathering fuel I grew as warm as if I had been able to luxuriate before a roaring blaze. So there were compensations in the fuel problem after all.

The storm that had heralded my arrival lasted for three full days, but on the fourth day the weather changed abruptly and the arctic spring exploded in a violent eruption. On June the 1st, the sun shone down upon me with a passion that it hardly knows even in the tropics. And it kept on shining for eighteen hours out of every twenty-four.

In half a day the snow that lapped my observation ridge retreated a dozen feet, leaving the exposed gravel and dead moss to steam away like an over-anxious kettle. It was a queer thing to see, and I felt as if I were sitting on the summit of a frozen world that inexplicably, and with an unbelievable swiftness, had decided to collapse and melt away.

Every hollow and low-lying spot harbored a freshet that quickened and murmured without pause for rest, even during the brief twilight period that passed for night. The ice began to rot. The shining surfaces turned leaden, dulled and fractured into countless millions of tiny, separate rods that were held upright and together only by their mutual pressure on one another. It was no longer possible to crawl about the drifts in search of wood, for the wet snow refused my weight. After twice plunging over my head into the snow I gave up the search for fear of suffocating in that wet and cold embrace.

And the birds arrived. One morning I was wakened from an uneasy sleep by the mad laughter of many voices chuckling in zany mirth. I flung open the door and found myself staring into the brilliance, and meeting the eyes of half a hundred disembodied heads. The heads were chickenlike, but stained dull red as if by the lifeblood of the bodies they had been parted from.

With something approaching horror I stared at the weird visitors and they stared back from maniac little eyes, and laughed until the whole valley rang with sound. I flung a piece of ice at one, and the whole flock suddenly took flight. As they cleared the ground, their trim white bodies that had been invisible against the snow were projected into view, and I knew them then for ptarmigan, the partridge of the arctic.

And so my first week drew to its conclusion, and the nature of the land had changed so violently that I could not comprehend the magnitude of that change. I was overwhelmed by the rapidity with which it had come about, and since I had only just begun to get acquainted with the frozen land, I was too confused to make much sense out of the fluid wastes that I now found myself marooned upon.

Yet there was a familiar quality in the warm, humid air that is the quality of plowed fields in the spring, though magnified a thousandfold. The sterile, unbreathing land of winter breathed deeply now, and its breath was that of a strong woman in the grip of passion.

A restlessness and a great unease kept me from sleep even during the brief interval of duskâthe last remnant of the long winter dark. Loneliness was driven from me. I, like all things in the land, waitedâfor what we did not know. The awakening perhaps of that impalpable entity which is the Barrens.

On June 4, I climbed a long, rocky slope behind the cabin for a glimpse of the lands that lay beyond the camp. I was sitting in the lee of a great boulder, avoiding the hot glare of the sun, when I heard the cries of dogs from far up the half-frozen river. At once I was confused by an anticipatory excitement combined with a strange hesitancy to disclose myself until I had seen the approaching stranger first. I started down the hill at the double, but checked my rush and retreated nervously to the shelter of my boulder. I was still there when the dogs came into viewânine immense beasts hauling a sled that dwarfed them, for it was over twenty feet in length. Two massive runners with sparse crossbars supported a pile of deerskins, and on the skins was the figure of a man.

The team drove along the river's edge to avoid the thaw stream on the surface and the sodden drifts on shore. When it was opposite me and I could see that the driver was no Eskimo, the dogs swung inshore and halted in the cabin yard. Nevertheless I still clung to the shelter of my rock, for now that the moment had arrived, I felt very dubious about the nature of my reception at the hands of this isolated man who saw no strangers from one year's end until the next. So, weakly, I postponed the moment, and watched as the man got slowly from his sled and stood beside it, staring intently at the cabin door.

If his arrival had been a shock to me, it was at least an anticipated one. To him, the shock of arriving home and seeing that someone had been living in his camp must have been tremendous. He stood quite still for several minutes. Then he leaned over the sled and withdrew his rifle from its case. Rifle in hand he walked forward to where my ax was lying, and picked it up, staring at it as if it had been some celestial object fallen from the skies. Long afterwards he told me how it had been impossible for him to resolve the turmoil in his mind when he arrived home and found this mute evidence of a strange visitor.

You see, he had lived all his life in a land where strangers do not arrive as if by magic from another sphere. He had looked for tracks of dog teams and had seen none, yet he knew of no other way that a man could come to Windy River in wintertime. There are no strangers in that landâunless you count the unseen ones who dwell amongst the rocky hills and are not of human kind.

With his rifle in hand and fear in his heart, he opened the cabin door and stepped inside. The litter of my belongings and the strange supplies must have baffled him completely, but he stayed inside, and I chose that time to descend from my hill.

2. The Intruders

2. The IntrudersThe dogs saw me at once and before I had reached the sled their hysterical outcry brought the man to the door with rifle crooked over his arm and his face blank and expressionless.

It was a tense and uneasy meeting. Franzâthat was his nameâlike all men who live too long alone, had lost the hard shell that human contacts build for us. Such isolated ones become soft and defenseless on the outside, and so they come almost to dread even the casual meetings with their fellows that are routine to us.

That is but part of the resentment that men like Franz feel for the casual stranger. There are other things. I think that only in such tremendous isolation does one feel the fear of his own species that is a throwback to primeval days when any stranger was a potential enemy.

I set about explaining myself and my presence at the cabin as best I could, but the words sounded rather lame.

Franz gave me no help at all, though he showed visible relief when he discovered that I had come by air. After I had said my piece, he stood for a good five minutes staring stolidly at me without uttering a word, and I had ample time to study him.

He was still very young, but with an unkempt air about him that made him seem much older in my sight. He was not tall, but slender with a lithe, wild look. He wore an unidentifiable hodgepodge of native skins and white man's clothes, and on his head he wore a tattered aviator's helmet of the sort that children wear about our city streets. The helmet peak was down and half-obscured his face. Black eyes were in its shadow, and below them a prominent and uncompromisingly Teutonic nose set on the smooth, Asiatic background of an Indian face.

His unblinking scrutiny was rapidly unnerving me, and then I had an inspiration. Remembering what I had always heard about the North, I made a stumbling appeal for hospitality. Blankness faded from his face, he smiled a little and stepped into the cabin, beckoning me to enter.

I felt that I needed a stiff drink, so I burrowed in my kit and produced a bottle. Without asking Franz, I poured a drink for each of us. I suppose it was the first that he had ever had. He gulped it down, and as he coughed and wiped tears from his eyes, his frozen taciturnity began to thaw, then melted with the same untrammeled rush that the snows had shown in the first spring sun. He began to talkâstiffly at first and in awkward monosyllables that slowly grew together and became coherent. Eskimo and Cree words were mixed with English, but as his conversation reached full flow, the native words dropped out and his facility with a language that he had little call to use returned to him.

Oddly enough he asked no questions and betrayed no curiosity about me after the initial explanations had been made. Instead he talked of the long trip that he had just completed, and from that point his talk worked backward through the winter, into the years before. Finally, when dawn was with us, he was back as far as childhood's memory would recall. It was an amazing experience that he and I went through that night. I listened as I have never listened to another man, and Franz talked as if his voice had been denied to him since childhood days. His story was the tale of the intruders in the land, and of their struggle to make the land their own. And his tale gave me a chilling insight into the manner in which the Barrenlands had kept themselves inviolate from us.

His father, Karl, whom he worshipped with a restrained simplicity, had come to Canada from Germany, three decades earlier. The immigrant brought with him some of the memories of a cultivated man, but for reasons of his own he shunned the semi-civilized South of Canada and wandered to the North. Here, in due time, he found a wife amongst the mission-trained Cree Indians who live on the south verges of the high Northern forests. Karl's wife was a good woman and she was a good mother to his children, bringing them the best of the Cree blood, which is not inferior to that of any race.

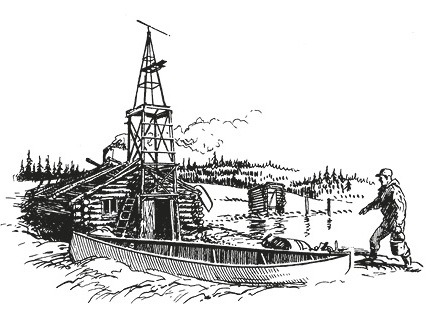

About 1930, the trading company at Nueltin Lake asked Karl to be their manager there. He accepted, and after a three weeks' canoe trip north from Brochet, the family arrived at Windy Bay. But it was a somber arrival, for the log building of a departed rival trader which Karl had hoped to use had been burned to the ground. And so, with autumn already bloodying the dwarf shrubs of the plains, Karl and the seven children had to build a winter home out of the meager trees that could be found.

When the one-room shack was finished and roofed with caribou skins, Karl was ready to do business. He anticipated no opposition in dealing with the Eskimos, for he was the only trader within two hundred miles. And his customers were the men that I had come to see, the People of the Barrens.

It must have been a strange childhood for Franz and for his brothers and sisters. They kept aloof even from the Eskimos. And the tiny outpost was visited only once each summer from “outside” when a canoe brigade arrived from Brochet to bring in the winter stock and carry out the season's fur. For the rest of the long months that stretched into years, only the deer kept Karl and his family company. The tremendous forces of the land beat down on the intruders without interference and drove them in upon each other. But the children, growing into youth in the protracted isolation of the place, slowly adapted to the land.

In the '30s the People of the Barrens were still numerous enough so that nearly forty huntersâall heads of familiesâ could come to trade their fox pelts at the little post. But as the years passed, so passed the hunters. Their names upon the “Debt books” of the post were lined out one by one, and there were few new ones to take their places. The price of pelts on the world's markets fell and so the profits of the post fell off. At last the company decided to withdraw, and in due course that message came to Karl.

The message came and Karl received it gratefully, for during the winter of that year his wife had died, and this man who had never been able to put away his fears of the land was now desperately lonely.

And so it was that when the fall came, the tiny cabin by the shores of Windy Bay stood empty to the wind. When the Eskimo hunters came south with fur, they found the door open and snow piled within the room, but nothing else. The Eskimos returned without the food and shells that they had counted onâand by spring there were many of them who would live to hunt no more.

Yet though Karl had left the land with a vast relief, it was not so with his children. Down in the forests where there are many trading posts and many men, Franz and the other children found a way of life they did not like.

Unlike most mixed-bloods, Franz was, by reason of his long isolation, quite unprepared to meet the barriers of race. The inevitable rebuffs that he was forced to accept from the race-conscious white men of the trading posts, who make a practice of holding aloof from the “savages,” as they are wont to call them, turned Franz in upon himself in a way that the Barrens had never done. He had not learned to think of himself as Indian, or as half-breedâbut as a white man. He could not fit himself into the miserable borderline existence that is the best the “breeds” can ever hope to know. Instead he remembered the great open plains of the North, the limitless lands where he was a man at his own evaluation. He remembered, too, the grave by the abandoned cabin, for Franz had loved his mother.

Though Franz was the eldest, and so felt it more deeply than the others, the rest of the children were also becoming aware of the social divisions of mankind, and they too recalled the Barrens with the regret of children who remember happiness.

In the late '30s Karl gave way to the desires of his children and undertook the long journey back to the shores of Windy Bay. But concern for the happiness of his children was not the only incentive. The price of white fox pelts had soared, and Karl was going back as a free trader who could gather the harvest of the Eskimos for a healthy profit, and at the same time make use of the trapping skill of his children. Nor was he disappointed in them, for Franz and his brother Hans became adept at the taking of the fox. Even the two older girls took part in the trapping, and they too came to be expert.

Yet the new life at Nueltin was not the same for Franz. He carried with him the bitter scars of his reception at the southern settlements, and as he ranged out into the plains, constantly expanding his trap line until he at last came into contact with the camps of the Eskimos, Franz was of two minds about them. They treated him as an honored guest and as an equal, and this treatment helped restore his self-esteem and relieve the bitterness. Yet he could not prevent himself from feeling the same superiority toward the Eskimos that the white traders had shown toward him.

I suppose it was this conflict, and the essential need of restoring his hurt ego, which made Franz blind to the slow fate that was relentlessly destroying his new-found friends. He became contemptuous of the apparent improvidence that seemed to bring the Eskimos only starvation. He echoed the sentiments of the white men who had belittled himâand perhaps he was also echoing his father's sentimentsâwhen he called his friends “ignorant natives.” He did not care to try to understand the nature of the evils destroying the People of the Barrens. In his own way, he even contributed to those evils, while with the part of him that was restored and revived by the Eskimos' friendship he was extending aid to them in their dire need.

The trading post of course was open once more and so the dozen surviving hunters of the People again gave up the pursuit of game for food, in favor of the pursuit of fur. They brought their furs to Karl and received only a token of their value, for Karl had neither friendship nor sympathy for them. Living in the Barrens again, he was beset by the memory of his wife and by the loneliness that his children did not share. He hated the land, and it was his desire to make enough money to be able to leave it behind forever. Since he was a free trader and had no overseer to watch his policy, he was able to harvest all the colossal profit margin which is considered legitimate throughout the North.

Then, in 1943 an event occurred that decided Karl on leaving the great plains. His eldest daughter, Stella, the one whom he most loved, was lost in the winter barrens for fifteen days.

The girl had been returning from a visit to a distant meat cache and she drove her own team, following the team of her brother Hans. Hans was then sixteen and Stella fifteen.

Some thirty miles from Windy Bay a blizzard enveloped them. Hans tied the lead dog of his sister's team to the back of his own sled and they drove on, trusting to the wind to remain steady so that they would not lose direction.

The blizzard rose to its full fury in one angry blast a few minutes after it had begun. Hans could not see his sister, nor could she see him. The wind was so violent and the ground drift so thick Hans did not notice that the traces of his sister's team had snapped between the lead dog and the next in line. Hans drove forward and a single dog followed him, dragging the broken traces.

Not knowing the trace had snapped, Stella rode on, sitting on her sled and keeping her face covered from the vicious gale. Her dogs were young, and without the leader they lost the trail at once, for it was blown over and obliterated moments after Hans's sled had passed.

Then the wind began to veer southward. Hans felt the change and was able to keep his team on course, but the dogs of Stella's team continued resolutely into the teeth of the veering wind. When Hans arrived at the post at last, he discovered what he had not known till thenâthat he was alone.

There was no hope of going back and searching. It was suicidal even to think of going out into the mounting storm. So the family sat about the stove and waited for the wind to drop.

The blizzard lasted only a day, but it was fifteen days before Stella returned to Windy Camp. It is a true measure of how well the children had become part of the land that this girl managed to survive midwinter in the Barrens with almost no food, and with no bedding, for better than two weeks.

She realized that she was lost, and she did the only sensible thingâmade camp. With her snow knife she cut a few blocks for a windbreak and burrowed into a drift behind the blocks. When the storm died she emerged and tried to decide where she was. But there are no landmarks in winter, not so much as a weedtop above the snow. The change in wind had gone unnoticed, and so Stella believed that she was a day's travel farther north than she really was. For the four hours of daylight she traveled south by the sun, but an overcast sky followed that first day, and for a week there was no sun. After three days her dogs were so famished that they could not pull, for she had long since abandoned the meat load she had carried on the sled. Now she cut all the traces, letting most of the dogs go in the hope that they would find their ways home alone. Three of the dogs she killed, for she needed their meat. Then she left the sled and walked on, carrying nothing but one thin robe and a pack of dog meat on her back.