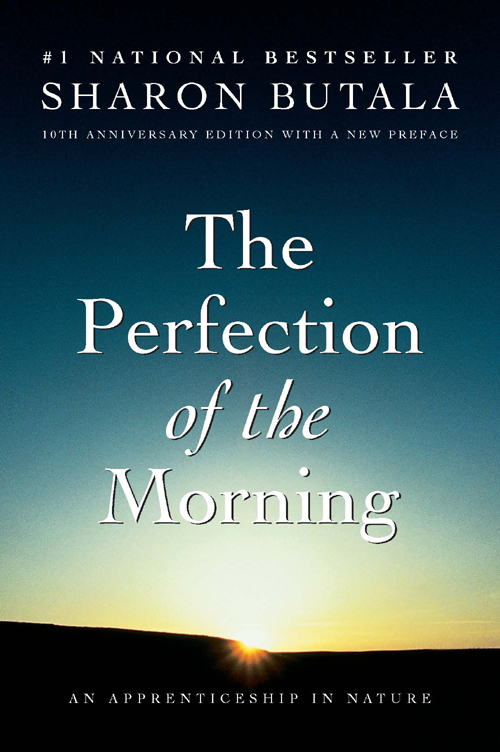

Perfection of the Morning

Read Perfection of the Morning Online

Authors: Sharon Butala

An Apprenticeship in Nature

Sharon Butala

To Those Who Knew This Land in Ancient Times

PREFACE TO THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION

Praise for The Perfection of the Morning #1 National Bestseller

When I published this book in 1994, although its writing felt necessary to me, I had no great hopes for it. I was happy that it was being published, but I rather expected that people simply would not believe what I had to say, despite my recounting of the long travail during which I learned it. That ten years later this book is still in print is a welcome surprise, not only because most books go out of print soon after publication, but because, just as this book spoke to certain Canadians in 1994, it must be continuing to speak to others. I venture to say that it perhaps opened up possibilities for other authors who wanted to write about nature in a new way—new to our generation, although not new in the English-language world of letters—that is, about the way nature affects us all spiritually, about its inexplicable power over the senses, about the way it enters one’s dreams at night and opens the psyche to a new and profound realm, about how we need it for much more than a source of livelihood or for recreation. Humans wholly severed from the land, as many North Americans are in danger of becoming, have lost a dimension of their very humanity.

By the time this new edition is published I will have been here on the land in southwest Saskatchewan just short of thirty years. The

loneliness I speak of in this book has abated, the deep spiritual crisis has ended, or at least, mitigated enough that life is mostly enjoyable. If none of these things had happened to me, I would not have had to delve so deeply inside myself for sustenance: I would not have become a writer. But my profound respect for the land grows stronger, even as I age and find it more difficult to spend the hours that I used to walking on the prairie. My humility in the face of the vast knowledge about land of the Aboriginal people of the Great Plains continues to grow, and my regret that we took so long to hear what they were trying to tell us grows in proportionate measure.

It was my husband’s dream that his thirteen thousand acres of unplowed native grass, where most of this book takes place, would remain in a natural state. In 1996 we made arrangements with the Nature Conservancy of Canada and the Saskatchewan government, to make them the owners of what had been the Butala ranch. In 2003 and 2004, fifty head of pure blood Plains buffalo calves from the Elk Island Preserve, twenty-five males and twenty-five females, were introduced onto the ranch, now called The Old Man On His Back Prairie and Heritage Conservation Area. Together with the prairie restoration efforts on the few plowed acres, Peter says what has happened is even more than he dreamt. We look forward to a peaceful old age together, filled with, instead of regret about what has been lost forever, some measure of satisfaction.

And yet, a part of me has great tenderness still for those early years when, in sometimes near-despair, or filled with awe, and often fear, I learned to walk the prairie, and to give myself over to its wonders.

Sharon Butala

The Frenchman River Valley

December 27, 2004

In 1976 when I was thirty-six years old I married my second husband, Peter, and came here to live on his ranch in the extreme southwest corner of Saskatchewan, just north of the Montana border. Although I’d been born in Saskatchewan and had lived here all but five years of my life, I had arrived in a landscape that, although I found it extraordinary, was not only unfamiliar to me, but of a kind I hadn’t even known existed in this province. I hadn’t studied it in school, since no early explorer had crossed it, no one going this far south, the miles and miles of open plains being as daunting as an ocean to a nineteenth-century traveler. In my car trips across the country I hadn’t seen it, since no major highways went through its heart; everyone I knew holidayed either in the lake country of the north, or the Qu’Appelle Valley in the southeast, while southwest Saskatchewan, as far as I knew, had only the tiny man-made lake in the center of Cypress Hills Park, and no major river systems. Now it seems amazing that I knew nothing about a place that covers about 28,000 square kilometers, is five times the size of Prince Edward Island and slightly bigger than Vermont.

Southwest Saskatchewan is best grasped as part of the vast Great Plains of North America which extend north to Edmonton and

south into Texas. It’s a high plateau—the Butala ranch is at a typical one thousand meters—and it seemed from the first time Peter took me there that I knew this, as the terrain and even the air in some nebulous way seem to breathe of altitude. Its topography is low rolling hills and flat or sloping grassy areas cut here and there by coulees, chasms of varying sizes eroded by rain and meltwater in which shrubs or, in the larger ones, trees, often coniferous, grow. There are virtually no trees growing naturally elsewhere—a nearby municipality is called Lonetree—and no other shelter. Coulees provide the only refuge from the insistent, inescapable burn of the summer sun or from winter blizzards, and are havens for deer, rabbits and other small animals and birds. They are always fascinating places to explore since their steep clay sides provide dens for bobcats or coyote families and high places for golden eagles to anchor their large, reusable nests built of sticks.

The climate is one of extremes, with temperatures ranging from minus fifty Celsius to highs of plus forty Celsius. A constant, steady wind in winter brings on blizzards of appalling severity and in the summer heat, tornadoes which, because of the thin and scattered population, usually do little damage, and are frequently not even reported. The severe climate I was used to as a native Saskatchewanian, but, also used to battling mountains of snow all winter, I was surprised to find that some winters, month after month, the pale ground, frozen hard as rock, would be covered by only the occasional skiff of thin, dry snow. In the early years, before I’d gotten used to the winters here, I found it depressing to look out my kitchen window and see, instead of fields of glistening snow shading from purple to blue to white to silver, dun-colored barrenness day after day all the long winter. But this area of the province is blessed with Chinooks, too, which blow in from Alberta now and

then during the winter, their warm winds taking away what snow there is, and bringing sudden, springlike temperatures in the midst of the deepest cold.

As the American writer Wallace Stegner—a resident of Eastend (the town nearest us) from 1914 to 1920—has pointed out, the true West on both sides of the border is defined by its aridity, and in practical terms, settlement has always been determined by the availability of drinkable water, of a reliable supply for livestock, and sufficient moisture to grow crops. I didn’t know it at the time, but the place I was about to call home is situated in the driest part of a region so dry the annual precipitation runs to only about thirty-one centimeters (twelve inches).

Water is indeed a scarce resource: the lack of it determines also the flora—species which conserve water, like cactus—the fauna—which must be able to go long distances for water, or to make do with little of it—and the livelihood of its inhabitants. After I’d been here for a while I began to sense that the constant worry about having enough of it for even the most basic needs also helps set the character of the people, for the older generation tends to be determined sometimes to the point of rigidity, having a touch of grimness which makes belly laughs fewer than rare, who instead find relief in a more reliable laconic, dry humor.

As in much of the true West, rivers are few, small and tend to run dry in drought years. South of the South Saskatchewan, the region’s northern boundary, the only true river is the Frenchman, which runs out of the Cypress Hills, more or less southeasterly till it crosses the border into Montana near Val Marie, eventually emptying into the Missouri-Mississippi river system. The Frenchman was once called the “White Mud,” after the outcroppings of high-quality white clay that gleam in the sun on bare cliffs along the

river valleys. To this day that clay is mined in the Ravenscrag valley running west of Eastend, and carted off daily to Medicine Hat where it is turned into irrigation tiles and sundry other ceramic utensils and vessels.

Before the advent of settlers or even ranchers, the river was called the Frenchman in the United States and the White Mud in Canada, and on early maps (I have seen one dated 1875), there was a gap between the two. When it was demonstrated that they were the same river—how can I help but wonder who first made that trip of discovery, although his name is unrecorded?—the name was changed in Canada to the Frenchman. The other major streams are both called creeks: Swift Current Creek and the historic Battle Creek—“historic” because the Cypress Hills Massacre took place there in the spring of 1873, the event which finally brought the North-West Mounted Police to the West. During the worst drought years all three creeks may run dry, at least in places where there are no springs feeding them.

The area, in fact, had been designated historically as too dry for farming. It is part of the Palliser Triangle, a term not quite synonymous with southwest Saskatchewan, since the Triangle runs into southeastern Alberta. The area acquired this name through Captain John Palliser, an Irish army officer sent out by the British under the auspices of the Royal Geographical Society in 1857 to survey some of the Canadian West as to its suitability for agriculture. His report, not published till 1869, described a triangular area having the American-Canadian border for its base between 100 and 114 degrees longitude, with its apex at 52 degrees latitude, including most, if not all, of southwest Saskatchewan as unsuitable for agriculture.

But the Canadian government soon became eager to prevent Americans, whose policy of Manifest Destiny was causing them to

look over the border with a grimly acquisitive eye, from simply riding their horses into this uninhabited area and calling it their own. Palliser’s report was a deterrent to settlement for a while but in time, with the encouragement of others who traveled over and studied the same territory, bringing back more favorable reports (none of them, Palliser included, reaching as far south as where I sit writing), it was opened to farming regardless. Palliser’s pronouncement, although an unwelcome and frequently maligned one, contains enough truth that it can’t be erased, and to this day it hangs over the land.

The most striking geographical feature, and the one even I had heard about, is the Cypress Hills north of here, lying across the Alberta-Saskatchewan border and extending so far south and east as to account for Eastend’s name. The hills peak at an extraordinary 1,392 meters, the highest point in Canada between the Rocky Mountains and a high point in Labrador. There are no cypresses in the Cypress Hills: the lodgepole pines which actually grow there were misnamed by the Métis, who used the word to mean “jack pine.” Because of their straightness and height, these pines were used by the Natives as tepee poles.

Not only are the Hills beautiful but, together with a tip in the Wood Mountains about three hundred kilometers southeast, they are unique in the West. During the Pleistocene ten to twelve million years ago when glaciers scraped down this area, the highest part of the Hills remained above the level of the ice. To this day certain montane species of flora, which occur elsewhere only in the Rocky Mountains two hundred miles to the west, can be found there.