Pericles of Athens (14 page)

Read Pericles of Athens Online

Authors: Janet Lloyd and Paul Cartledge Vincent Azoulay

The first episode was recorded in the fourth century by Douris of Samos, who was well

placed to know of the affair since he was a native of the rebel island.

22

In the course of the conflict, some Athenian prisoners were captured by the Samian

rebels, who tattooed their faces with an owl. Gratuitous cruelty? Not at all. The

rebels were simply paying back the Athenians who, earlier, had marked the faces of

enemy prisoners with the prow of a Samian ship, the

Samaina

.

23

By recording this incident, Douris clearly intended to underline the Athenians’ initial

responsibility in this unleashing of violence. However, the episode took on another,

less immediate significance. By tattooing their prisoners in this way, both groups

of belligerents turned them into monetary symbols and consequently into interchangeable

merchandise—for, just as the owl was the monetary symbol of Athens, the

Samaina

was that of Samos (

figure 3

).

24

Furthermore, this story may reveal the true cause of this bloody conflict. Over and

above the reasons alleged by the ancient sources, the main objective of the repression

led by Pericles may have been to impose upon Samos the use of Athenian coins. The

Samians appear to have refused to apply Clearchus’s decree, which was probably passed

in the early 440s and imposed upon all the allies the use of Athenian weights and

measures and silver currency.

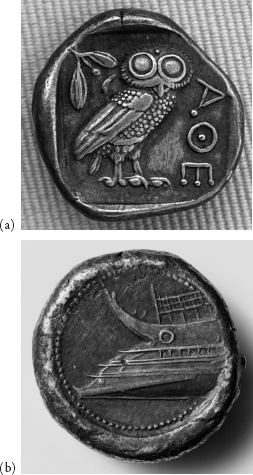

FIGURE 3.

A coin war: (a) Athenian silver tetradrachm, minted 449 B.C. 17.07 grams. Owl facing

right. SNG Copenhagen 31. Photo © Marie-Lan Nguyen. (b) Silver tetradrachm, minted

in Zancle (Messana) by the Samians between 493 and 489 B.C., showing, on the reverse,

the prow of a Samian ship (

Samaina

). Image © Hirmer Fotoarchiv.

However that may be, the Samos affair shows us a Pericles who resorted to unbridled

violence, as the outcome of the conflict testifies. After the Athenians’ victory,

the Samians “were reduced by siege and agreed to a capitulation,

pulling down their walls, giving hostages and consenting to pay back by instalments

the money spent upon the siege” (Thucydides 1.117.3). All this was altogether normal;

Athens applied victors’ rights and deprived the Samians of all attributes of sovereign

power: its ramparts, its fleet, and its currency. What was less normal though was

the cruelty that, again according to Douris of Samos, Pericles inflicted upon the

Samian elite: “To these details, Douris the Samian adds stuff for tragedy, accusing

the Athenians and Pericles of great cruelty. But he appears not to speak the truth

when he says that Pericles had the Samian trierarchs and marines brought into the

marketplace of Miletus and crucified there, and that then, when they had already suffered

grievously for ten days, he gave orders to break their heads in with clubs and make

an end of them, and then cast their bodies forth without funeral rites.”

25

In Douris’s version, the horror of the tortures—inflicted in Miletus, not in Athens—had

been intended to serve as a lesson addressed to the entire empire. But this account

aimed above all to emphasize not only the cruelty of Pericles, but his impiety: to

deprive bodies of the funeral rites was a grave transgression, the full implications

of which are revealed in Sophocles’

Antigone

. It may be that Douris is overdramatizing (

epitragoidein

) the events, as Plutarch, being concerned to protect the reputation of the Athenian

stratēgos

, claims; but in any case, Douris’s testimony underlines the existence of a tradition

hostile to Pericles that deliberately emphasizes his intolerable cruelty.

26

In fact, such a sinister reputation already surrounded Pericles’ father, Xanthippus.

Right at the end of the

Histories

, at a strategic point in his text, Herodotus produces an equivocal image of Pericles’

father: guided by vengeance, Xanthippus had the Persian governor Artaÿctes crucified

at Sestos, after having his son stoned to death before his eyes.

27

Perhaps this was a way for the historian, himself a native of Halicarnassus, implicitly

to cast blame upon the actions of the son by means of an account of his father’s behavior.

Herodotus presented Xanthippus as the initiator of a strategy of terror that reached

its zenith under Pericles.

28

Such cruelty was further amplified with the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War in 431,

as is shown by the expulsion of the Aeginetans in the first year of the conflict.

Here too, it was probably Pericles who initiated that repression.

The Expulsion of the Aeginetans

Within a context of exacerbated tensions, the

stratēgos

decided to punish the Aeginetans even though they had not, in fact, revolted against

Athens. That, at least, is the version favored by Plutarch: “By way of soothing the

multitude who … were distressed over the war, he won their favor by distributions

of

moneys and proposed allotments (

kai klēroukhias egraphen

) of conquered lands; the Aeginetans, for instance, he drove out entirely and parcelled

out their island among the Athenians by lot.”

29

There were, in truth, several reasons why Aegina was punished in this way. In the

first place, it had always been an undisciplined ally that had been late in joining

the league (in around 459 B.C.), and it was, furthermore an ancient naval power that

was a longstanding rival of the Athenians.

30

Second, the Athenians accused the Aeginetans of having provoked the war and encouraged

the Spartans’ hatred of Athens (Thucydides, 2.27.1); and last, the Athenians were

in need of a sure base for themselves, within reach of the Peloponnese.

Although Thucydides does not accuse Pericles directly, there can be no doubt that

he was implicated in this business. One of the only statements actually attributed

to Pericles—for he left no writings of his own—refers precisely to the fate of the

island, “urging the removal of Aegina as ‘the eye-sore of the Piraeus,’”

31

and evoking the sticky substance that gathers on the lids of an infected eye. In

this way, Pericles assimilated the island of Aegina to a bodily secretion that the

Athenians were invited to suppress by means of an appropriate treatment. The metaphorical

scorn reflected the real violence to which the Aeginetans were subjected at the beginning

of the Peloponnesian War.

Pericles’ career, from the Euboean affair in 446 down to the expulsion of the Aeginetans,

definitely suggests an unchanging attitude toward the allies. However, in this respect,

the

stratēgos

was no better and no worse than anyone else and was by no means original. He was

simply continuing a policy that was initiated before him—

pace

the admirers of Cimon such as Ion of Chios and Stesimbrotus of Thasos—a policy that

was also continued after him, whatever the critics of Cleon, such as Thucydides, have

to say.

32

But what distinguished Pericles was the lucidity that he acquired from this experience

of warfare punctuated by brutal episodes. The

stratēgos

developed a deep line of thought on the empire and the necessity of maintaining it.

It was a choice that he theorized in words and materialized in grandiose monuments.

The Spectacle of Force and Pericles’ Presentation of It

The Theorization of Imperialism: A Necessary Injustice

If there is one original aspect to Pericles’ attitude to imperialism, it lies not

so much in his practice as in the way that he represented the empire both to others

and to himself. In the speech that he made in 430, faced with the anger of the Athenian

people, the

stratēgos

set out a particularly lucid analysis of the Delian League and the way that it worked:

You may reasonably be expected, moreover, to support the dignity which the city has

attained through empire—a dignity in which you all take pride—and not to avoid its

burdens, unless you resign its honours also. Nor must you think that you are fighting

for the simple issue of slavery or freedom; on the contrary,

loss of empire is also involved and danger from the hatred incurred in your sway

. From this empire, however, it is too late for you ever to withdraw, if any one at

the present crisis, through fear and shrinking from action does indeed seek thus to

play the honest man;

for by this time the empire you hold is like a tyranny, which it may seem wrong to

have assumed, but which, certainly, it is dangerous to let go

. Men like these would soon ruin a city if they should win others to their views,

or if they should settle in some other land and have an independent city all to themselves

(Thucydides, 2.63.1–3).

The

stratēgos

conceded that it was perhaps unjust to change the Delian League into an empire at

the service of Athens. However, there could be no question of reversing the decision,

for to do so would be to accept slavery,

douleia

.

33

His reasoning is subtle: it is necessary to defend an empire, even one that is acquired

by coercion, for it would be too dangerous to give it up. If the allies cease to be

in thrall to Athens, they will not remain neutral but will switch over to the enemy

in order to wreak vengeance for the tribulations that they have suffered. In his speech,

Pericles, rather then retreating on the subject of imperialism, goes into the attack.

However unjust it was, the people must continue to act tyrannically toward the members

of the League.

34

There can be no question of dismounting once one’s steed is already charging.

Convinced of the necessity of the empire, Pericles furthermore undertook to lend legitimacy

to the power of Athens by means of monuments that, over and above their proclaimed

purpose, gave material expression to the city’s new imperial status.

The Odeon and Xerxes’ Tent: From One Empire to Another

The Odeon, constructed between 446 and 430 B.C., was associated so closely with Pericles

that Cratinus, the comic poet, had one of his characters declare: “The squill-head

Zeus! Lo! Here he comes, the Odeon like a cap upon his cranium, now that for good

and all the ostracism is o’er.”

35

The Odeon as headgear: what better way of expressing the link that bound the monument

and the

stratēgos

together?

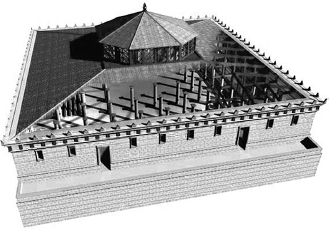

Today, this building is little known, for the archaeological excavations were never

completed. But in Antiquity, it was considered one of the most impressive monuments

in a city that was rich in architectural marvels (

figure 4

). The precinct in which it stood could accommodate huge crowds: this Odeon, flanking

the theater of Dionysus, which was at that time built of wood, appeared as an immense

hypostyle construction—with multiple colonnades—of 4,000 square meters in area (around

43,000 square feet). It was the largest public building in Athens and the first theater

in Antiquity ever provided with a roof.

FIGURE 4.

The Odeon of Pericles (ca. 443–435 B.C.): a virtual reconstruction. Image © the University

of Warwick. Created by the THEATRON Consortium.

At an architectural level, the Odeon was freely inspired by Xerxes’ tent, which had

been brought back to Athens, as booty, after the victory at Plataea, which the Greeks

won over the Persians in 479 B.C.

36

According to Plutarch: “The Odeon, which was arranged internally with many tiers

of seats and many pillars, and which had a roof made with a circular slope from a

single peak, they say was an exact reproduction of the Great King’s pavilion, and

this too was built under the superintendence of Pericles” (

Pericles

, 13.5). One should, incidentally, not be misled by the vocabulary, Xerxes’ “pavilion”

or “tent” resembled a real palace that could be dismantled and transported elsewhere

and that adopted the form of the imperial residences of Persepolis. Its true model

was the Apadana and the palace of a hundred columns, a reception hall built by Xerxes

himself.

37

In adopting such an architectural style, Pericles was modeling his Odeon on the great

imperial architecture of the Achaemenids.