Pericles of Athens (39 page)

Read Pericles of Athens Online

Authors: Janet Lloyd and Paul Cartledge Vincent Azoulay

Mirabeau’s reply to him in the Assembly came the very next day, pointing out the inadequacy

of that ancient analogy: “He [Barnave] has cited Pericles waging war so as not to

have to present his accounts. According to what he says, does it not seem that Pericles

was a king or some despotic minister? Pericles was a man who, knowing how to flatter

the passions of the populace and win its applause as he left the tribune, by reason

of his largesse and that of his friends, dragged Athens into the Peloponnesian War.

… Who did? The national Assembly of Athens.”

108

In this way, Mirabeau put his opponent straight: in the first place, Pericles was

not the king of the Athenians; and second, it was the Athenian Assembly that voted

for this disastrous war—not some kind of sovereign. So Barnave’s reference to Pericles

did nothing to advance his own cause!

109

All the same, over and above their differences, the two orators were in agreement

on one point: Pericles was indeed a corrupt and corrupting warmonger.

On the other side of the Atlantic, criticism was equally ferocious. The American republicans,

influenced as they were by their readings of Plutarch

and Plato, had no sympathy at all for fifth-century Athenian democracy, which they

judged to be unstable and anarchical. They far preferred that of Solon.

110

But it was the Romans who fascinated them the most. Significantly enough, when the

founding fathers of the American nation met in Philadelphia in 1787, they set up,

not a Council of the Areopagus, but a Senate that was to meet in the “Capitol.”

Even when not totally ignored, Pericles became a target of virulent attacks. Alexander

Hamilton (1757–1802), who founded the Federalist party and was an influential delegate

to the 1787 Constitutional Convention, launched a direct attack on the

stratēgos

in an article in the

Federalist Papers

on 14 November 1787. At this point, we should note the importance of this collection

of papers. It was designed to interpret the new American Constitution and promote

it. Using the pen-name “Publius,” a pseudonym chosen in honor of the Roman consul

Publius Valerius Publicola, Hamilton confirmed all the anti-Periclean clichés: “The

celebrated Pericles, in compliance with the resentments of a prostitute, at the expense

of much of the blood and treasure of his countrymen, attacked, vanquished and destroyed

the city of the Samians. The same man … was the primitive author of that famous and

fatal war which, after various vicissitudes, intermissions and renewals, terminated

in the ruin of the Athenian commonwealth.”

111

On both sides of the Atlantic, Pericles was thus presented as an unscrupulous warmonger.

112

A Liberty-Killing Tyrant: The Pericles of the Terror

In France, the nature of the attacks against Pericles underwent a change in the Convention

period (1792–1795). After the king was deposed, Pericles came to embody not a corrupt

orator, but a liberty-killing tyrant. Abbé Grégoire was the first to make this accusation,

in his report to the Convention dated 8 August 1793. What was at stake at this point

was the justification of the suppression of all scholarly academies and societies,

on the pretext that they had placed themselves at the service of despotism: “Tyrants

have always adopted the policy of assuring themselves of vociferous fame; and so it

was in the case of Pericles who, after ravaging Acarnania in order to please his mistress,

through his example corrupted an Athens that was cowed by his skill and persuaded

historians to tell lies in his favor.”

113

According to Grégoire, Pericles in this way concealed his tyrannical power, thanks

to the scholars who served him and were prepared to misrepresent reality in their

works, just as did so many Academicians of the Ancien Régime.

Under the Terror, the

stratēgos

was yet again represented as a manipulating tyrant. However, he was invoked not as

a figure who encouraged a break with the monarchical past, but rather as one who anticipated

eventual

tyrannical consequences. That was, indeed, the purpose of Billaud-Varenne, a Montagnard

and member of the Committee of Public Safety, in his report dated 1 Floreal, Year

II (20 April 1794): “The wily Pericles clothed himself in popular colours in order

to conceal the chains that he was forging for the Athenians. For a long time, he made

the people believe that he never ascended to the tribune without telling himself,

‘Remember that you will be speaking to men who are free.’ And then that same Pericles,

having managed to seize absolute power, became the most bloodthirsty of despots.”

114

This was a transparent allusion to Robespierre, who was accused of pretending to

love the people, the better to obtain undivided power for himself. A few months later,

Billaud-Varenne broke off relations with “the Incorruptible Robespierre,” thereby

hastening the latter’s downfall.

After Thermidor and the execution of Robespierre, Abbé Grégoire turned that implicit

analogy into an explicit comparison: on 17 Vendémiaire, year III (8 October 1794),

in his

Rapport sur les encouragements, récompenses et pensions à accorder aux gens de lettres

et aux artistes

(

Report on the encouragement, rewards and pensions to be granted to scholars, literary

men and artists

), he associated the Athenian

stratēgos

and the French Revolutionary in a common condemnation: “And in what century have

talents been more atrociously persecuted than under Robespierre’s tyranny? Pericles

drew the line at just ejecting the philosophers.”

115

Abbé Grégoire thus added intolerance to the long list of Pericles’ vices, thereby

following in the footsteps of that other abbé, Jean-Jacques Barthélemy.

At this point, Pericles vanished from the revolutionary scene. The fact was that,

under the Directoire, a few scholars occasionally challenged the use that had so copiously

been made of ancient references ever since 1789. In his

Lectures on History

, delivered in the Ecole normale supérieure in 1795, Volney launched into a violent

attack against “the new sect [who] swear by Sparta, Athens and Titus Livy.”

116

This orientalist sought to correct the ideas of his listeners and readers by presenting

a more realistic picture of Antiquity: “Eternal wars, the murder of prisoners, massacres

of women and children, breaches of faith, internal factions, domestic tyranny and

foreign oppression are the most striking features of the pictures of Greece and Italy

during five hundred years, as it has been portrayed to us by Thucydides, Polybius

and Titus Livy.”

117

Pericles’ Athens was by no means exonerated in this depressing judgment. According

to Volney, the masterpieces of Athenian art were “the primary cause” of Athens’s downfall

“because, being the fruit of a system of extortion and plunder, they provoked both

the resentment and defection of its allies and the jealousy and cupidity of its enemies,

and because those masses of stones, although well cut, everywhere represented a sterile

use of

labour and a ruinous drain on wealth.”

118

Periclean Athens, denigrated both before and after Thermidor, certainly was a major

victim of the Revolution.

An Alternative Tradition? Camille Desmoulins’s Liberal Pericles

Even though it was hard for them to emerge from such an ocean of criticisms, a few

rare signs do suggest the existence of an alternative tradition that was more favorable

to the Athenian

stratēgos

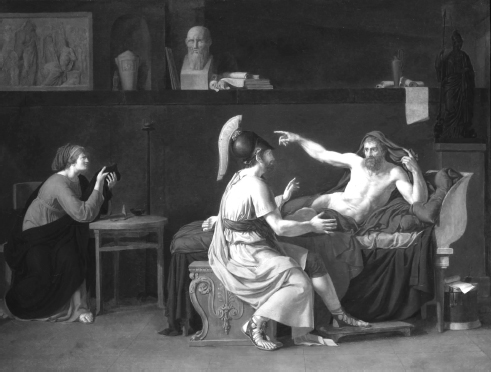

. At the pictorial level, the painter Augustin-Louis Belle (1757–1841) exhibited an

Anaxagoras and Pericles

(today in the Louvre) in the 1796 Salon (

figure 12

). The painting illustrated the scene in which the old philosopher, believing that

his friend has forgotten him, allows himself to starve to death (Plutarch,

Pericles

, 16.7). Although the choice of this episode testified to a certain interest in the

stratēgos

, it was nevertheless ambiguous, for it tended to underline the shortcomings of

Pericles. Anaxagoras’s extended arm was highly symbolic; it was as if the philosopher

was bidding the

stratēgos

to exit from the scene.

FIGURE 12.

Anaxagore et Périclès

(1796), by Augustin-Louis Belle (1757–1841). Oil on canvas. The Matthiesen Gallery,

London. © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) / image RMN / © Direction des Musées

de France. Photo courtesy of The Matthiesen Gallery, London.

It is definitely in the writings of Camille Desmoulins that the only positive view

of Pericles is to be found. When elected to the National Convention, Desmoulins took

his seat amid the Montagnards, but he felt nothing but disdain for Sparta. In truth,

he was one of the rare revolutionaries who possessed a solid knowledge of Greek culture.

119

Having progressively distanced himself from his great friend Robespierre, he founded

a new newspaper

Le Vieux Cordelier

(The Old Friar) in which he attacked the

Enragés

(“the Angry Ones”) and, in particular, their unbridled enthusiasm for Sparta: “What

do you mean with your black broth and your Spartan freedom? What a fine lawgiver Lycurgus

was, possessing knowledgeable skill that consisted solely in imposing privations upon

his fellow-citizens and who made them all equal just as a storm renders all who are

shipwrecked equal?”

120

In opposition to the mirage of Sparta, Desmoulins set up an idealized Athenian city.

According to him, only the Athenians had been “true republicans, lasting democrats

by both principle and instinct.”

121

However, it was not until the seventh and last number of

Le Vieux Cordelier

, dated Pluviose, Year II (early February1794) that Desmoulins celebrated Pericles

openly, praising his steadfast opposition to all forms of censorship. In particular,

he admired his ability to accept criticism instead of wiping it out: “So rare, in

both Rome and Athens, were men like Pericles. When attacked by insults as he left

the assembly, he was accompanied home by a Father Duschesne-figure endlessly screeching

that Pericles was an imbecile, a man who had sold himself to the Spartans. Even in

these circumstances, Pericles summoned up sufficient self-control and calm to say

coldly to his servants, ‘Take a torch and accompany this citizen back to his home.’”

122

We should, however, assess this praise correctly. In the first place, Desmoulins praised

Pericles only insofar as he protected freedom of expression, not as a promoter of

direct democracy. What he liked about Athens was, above all, “the freedom for each

man to live as he wished to and for poets and singers to laugh at contemporary politicians.”

123

Second, the impact of his writings was minimal, for this last issue of

Le Vieux Cordelier

circulated only in proof-form and was published only posthumously. One month later,

on 5 April 1794, Camille Desmoulins was guillotined, and his praise of Pericles resounded

hardly at all and remained without parallel.

Really without parallel? Perhaps not. Another member of the Convention, Marc-Antoine

Baudot (1765–1837), also seems to have swum against the anti-Periclean tide. Trained

as a doctor and a staunch Montagnard, he nevertheless had leanings toward the “Indulgent”

group, and after Robespierre’s

fall he was forced into exile, from which he returned only with the advent of Louis-Philippe,

in 1830. In one of his plans for an epitaph for his tomb, Baudot described himself

as

republicanus Periclidis more

, a republican in the manner of Pericles.

124

So was this a second revolutionary who was declaring loud and strong his preference

for a Periclean Athens? To believe so would be mistaken. That epitaph dated from the

1830s, not from the revolution itself. Baudot was probably kidding even himself when,

in his

Notes historiques

, he declared “I wanted a Republic in the manner of Pericles, that is to say one with

luxury, the sciences, the arts and trade. Poverty, in my opinion, is good for nothing

at all and I would join with Dufrêne in declaring it to be not a vice but even worse.”

125

In his youth, Baudot was in truth by no means a lover of Athenian luxury but on the

contrary poured anathema upon the wealthy. His exaltation of a bourgeois Pericles

does not date from the Revolutionary period. Rather, it reflects the tempered ideals

of Baudot in his twilight years. The fact is that, between 1789 and the July Revolution

(1830), there had been a radical change in paradigms: the nineteenth century saw the

construction of a bourgeois Athens, and here, Pericles once more headed the field.

CHAPTER 12

Pericles Rediscovered: The Fabrication of the Periclean Myth (18th to 21st Centuries)