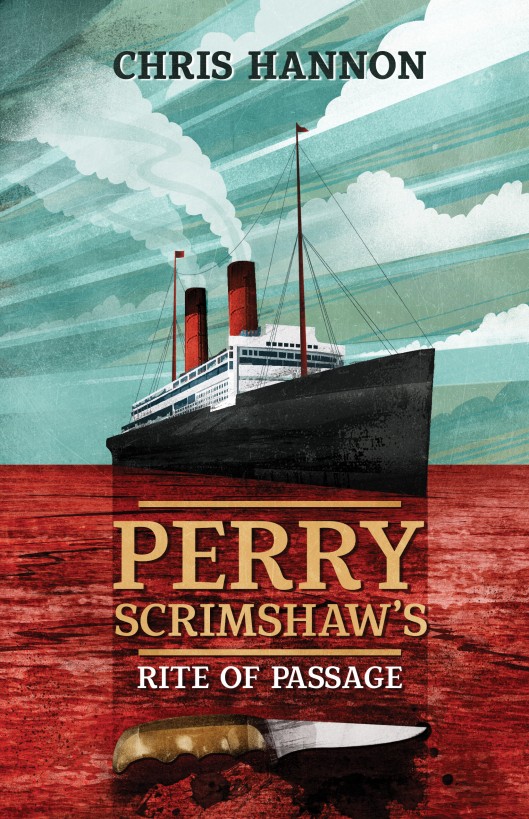

Perry Scrimshaw's Rite of Passage

Read Perry Scrimshaw's Rite of Passage Online

Authors: Chris Hannon

Tags: #love, #prison, #betrayal, #plague, #victorian, #survival, #perry, #steampunk adventure, #steam age

Perry

Scrimshaw’s Rite of Passage

Chris

Hannon

Copyright

©

2015 Chris Hannon

All rights reserved. This

book or any portion thereof

may not be reproduced or used in any

manner whatsoever

without the express written permission of the

publisher

except for the use of brief quotations in a book

review.

The right of Chris Hannon to be identified as the Author of

the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN

9781849147743

Published through Completely Novel.

We must scrunch or be scrunched.

Charles Dickens

,

Our Mutual

Friend

(for Toby)

T

he crescent moon cut belts of

shimmering silver onto the black water beyond. Perry gazed up at

the desolate sky, clear and starry. Was God watching him? Wooden

decking creaked underfoot, though he trod cautiously, seeking out

forms in the shadows under the iron benches and checking behind for

ambushes. The icy breeze buffeted and nipped at his ears, water

licked and lapped in the darkness, stifling his senses. At the end

of the wharf there stood a figure, black as a crow, waiting for him

to come.

Perry took a moment to dab a

handkerchief at the worst of his cuts, though there were too many

to attend to. He settled for tying it around the biggest wound on

his knee. The pain was sharp and true. He cursed his stupidity for

falling for that old trick, one he had played himself when he was

younger. But that wasn’t what really hurt, what really fuelled the

anger and hatred deep within. Would killing him assuage it? Right

the wrongs? Perry didn’t know anymore, but he knew he would

continue on to the end of the wharf.

With each step, the figure grew

larger; he was on the edge, facing out to sea, back turned to

Perry’s approach. Perhaps he wouldn’t need the knife at all, a push

might be all that it would take.

1

Bishopstoke, Hampshire,

1883

Atop a ladder, Samuel Scrimshaw

could see his kitchen table through the hole in the roof. He had a

lead sheet ready and his hammer was cradled safely in the iron

guttering. Samuel covered the hole with his palm.

‘

Perhaps I

should just stay up here and plug the breach with my hand,’ he

called down. It had been a rainy springtime and he’d patched it up

three times already. If only he could haul summer closer with his

bare hands…it would be less work.

‘

No,’ his

son’s voice carried up, ‘who’d cook for us if you’re stuck up

there?’

‘

Well,’ he

took four nails from his pocket, ‘I suppose I’d come down if it

wasn’t raining,’ he placed the nails between his teeth and slid the

lead sheet over the hole.

‘

Who’d walk me

to school if it was raining?’

Inwardly, he tightened. It was

Perry’s schooling that meant he couldn’t afford to replace the

leaky tap in the kitchen or repair the roof properly. Samuel

plucked the first nail from between his teeth and slotted it into

the hole in the corner of the sheet. Making young ‘uns attend

school by law and expecting common folk like him to stand the cost

didn’t seem fair or right. It was hardly the boy’s fault but still,

what was wrong with starting a prenticeship early? He brought the

hammer down with a satisfying thump.

Once the sheet was in place he

climbed down.

‘

That should

do it,’ he said, ‘thanks for holding me steady.’ He mussed up

Perry’s golden-brown hair with his big gardener’s hands. Perry

beamed back at him. ‘Can we go guddlin’ now?’

‘

I thought you

might say that.’

Bishopstoke

was a small place, caught between Winchester and Southampton,

provided for by the changeable River Itchen and surrounding

woodland. Perry’s favourite guddling spot was a short hike into the

woods. On the way, they both gathered kindling and small branches.

Samuel tied them into a bundle and carried them on his back.

Their riverside route was damp and

addled with tree roots, the air ripe with the dewy

spring.

‘

Silver

birch,’ Samuel pointed, ‘look at that cobweb stretched across that

alder.’

Perry

dutifully followed his signals. Samuel guessed that he liked it,

but perhaps didn’t love these small things as he did.

He was only a boy after all and

perhaps took for granted the countless shades of green the Lord had

created. Silver water gushed past, swollen by recent rainfall.

Samuel led Perry further upstream, where the trees on the bank

began to thin out and a flint footbridge came into view.

‘

I’m going ahead!’ and Perry sprinted off as boys that age

do. By the time Samuel got to the bank, Perry was already wading

into the river, trousers rolled up beyond his knees and sleeves

past his elbows.

‘

How cold?’

‘

Very,’ Perry replied.

Brave boy.

‘Let’s

see…how many will it be today?’

Samuel

sat on the bank

and let his feet dangle a few inches above the flow. Perry crouched

below, his chin an inch or two above the rippling water. Samuel

loved moments like this: wind rustling in the trees, a woodpigeon

cooing from some branch above and his son, staring into the glassy

current, showing patience and skill. Perry smiled. Good

boy.

Slowly, Perry lifted the trout from the

water as gently as if it were made of crystal.

‘

Good lad,’ Samuel whispered. ‘P

op it in the bucket and get another while I deal with

this one.’

Deal

was a kind word.

He didn’t want Perry to see him killing the fish proper. As he got

to his feet, the fish squirmed and writhed, its tail flicking the

pit of the bucket. It was a beaut, on its own enough for two

dinners at least. He thanked the Lord for his son and this knack he

had.

Not even his old grandpa could

match-

‘

Pa?’

Samuel looked up from the

slithering fish.

‘

Hurry up.

I’ve got another.’

That eve they feasted on fish

stew, cooked up with onions, leeks and carrots all grown by his own

hand on the Hebblesworth estate. He tucked Perry in and lay on his

own bed across the room. Though he wasn’t sleepy yet, he liked to

lie in the warmth and thumb through pages of his tattered bible by

candlelight. He didn’t have his letters, but it felt good to hold

something holy while he assembled his prayers in his mind. He

prayed his wife was looking down on them favourably, keeping them

both safe and healthy.

Before sleep

finally came, he was dimly aware of movement in the bed opposite.

Perry wriggled and laughed through his dreams yelling out ‘hey

leave that, it’s

my

slate!’ and ‘Five and twelve is seventeen!’

Schooling or no, it was good to

see his boy learning some.

At the start of June, Samuel,

the two other gardeners, the maids, servants and kitchen staff were

told to assemble on the lawn in front of Hebblesworth House. It was

the wife, Lady Hebblesworth who addressed them, talking at length

about the stock exchange before Samuel realised what was happening.

The husband, he assumed, was cowering inside somewhere. Only one

maid and the cook were to be kept on.

He queued on the perfect lawn

with the rest, waiting for his envelope.

‘

Thanks.’ he

took it off Lady Hebblesworth, but didn’t mean his words. He felt

the sorrow in her eyes. She hated having to do this. It was wrong;

this wasn’t woman’s work. He almost felt sorry for her but however

bad their fortunes, they wouldn’t struggle to feed their son. He

walked away, tearing open the envelope. A week’s pay. Dread filled

his heart.

Hands trembling, he stalked

over to the flowerbed and yanked a digging fork up from the

soil.

‘

Don’t do

anything stupid,’ one of the gardeners said.

The spikes were blunted and

claggy with soil. All eyes were on him.

‘

What’s he

doing?’ murmured Lady Hebblesworth, her hand flush against her

chest.

What

was

he doing? He wasn’t

sure. He glanced up at the house. Was that a figure in one of the

windows? The husband? The spineless bastard who couldn’t meet the

wronged faces of his own mistakes?

‘

Sam?’ one of

the maids said, taking a step towards him.

He met the troubled faces but

found he had nothing to say. His son. That was what mattered.

Digging fork still in hand, he stormed away from the house, away

from the frightened people on the Hebblesworth lawn. Samuel

snatched up a weeding sack. At the vegetable patch, he stabbed the

fork down, half-imagining it was Mr Hebblesworth’s throat. When he

levered up the soil, there was no blood. Just a clutch of carrots.

He tossed the stolen vegetables in his weeding sack and moved the

fork along to the next lot.

Summer passed, but Samuel

couldn’t find regular work. He foraged for berries and wild

mushrooms, went fishing while Perry was at school - at least he’d

scraped enough together for the boy’s tuition.

One November’s eve, he sat with

Perry by the hearth, warming his feet by the fire. Samuel felt the

cold more now that he was thinner. Perry’s weight held up right

enough, always accepting the bigger portions: a father’s toll.

Gusts of wind buffeted the house, whipping the fire into a

mesmerising dance in the hearth.

‘

It’s amazing

ain’t it?’ Perry said.

The fire crackled and hissed.

‘A warm fire’s the heart of any home. Throw another log on will you

son?’

Perry slithered out from under

his blanket. Samuel rubbed his hands together and splayed them out

to the flames.

The front door creaked.

‘Pa?’

‘

Any of them

will do Perry, they’re all dry.’

‘

There’s some

people here.’

Samuel twisted round. Perry was

flanked either side by a policeman, one with a heavy black

moustache. In the soft light, their uniforms were dark midnight

blue, buttons glittered silver.

‘

Come to me

Perry,’ he turned to the policemen. ‘Don’t you fellows

knock?’

‘

We were about

to but then the boy opened the door.’

‘

Are you

Samuel Scrimshaw?’ cut in the other.

‘

Yes, what’s

this about?’

‘

Perhaps you

should send your boy to his room for a minute.’

A cold shiver ran through him,

he looked down at Perry, clutching onto his hip. ‘Go on son, to the

bedroom.’

Perry did as he was told.

The moustachioed policeman took

a step towards him, ‘I think you know what this is about.’

He did.

‘

Please,’ he

said, ‘it was only for my boy. Some blackberries, a few apples here

and there. We can barely scrape together enough to eat,

please.’

The policeman had a set of

wooden cuffs dangling in his right hand. Surely they weren’t here

to take him away? This was all wrong.

‘

Please…I-’

‘

-Apples did

you say? Wasn’t at Mr Sexton’s place past the Anchor

inn?’

‘

It was,’ he

admitted slowly, wondering why two policemen would be sent to

question a scrumper. Wasn’t there enough real crime going on? But

he knew he couldn’t say as much.

‘

They’ve an

orchard there, fruit just falling to waste and rotting on the

ground. Me and my boy have to eat - you wouldn’t put a man in

lockup for that, surely?’