Peter and the Starcatchers (2 page)

Read Peter and the Starcatchers Online

Authors: Dave Barry,Ridley Pearson

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Fiction, #General, #Family, #Social Science, #Fantasy, #Action & Adventure, #Magic, #Friendship, #Pirates, #Juvenile Nonfiction, #Orphans, #Nature & the Natural World, #Humorous Stories, #Orphans & Foster Homes, #Adventure and Adventurers, #Islands, #Folklore & Mythology, #Characters in Literature

CHAPTER 61:

Crenshaw Returns

CHAPTER 62:

Peter’s Decision

CHAPTER 63:

Gone Again

CHAPTER 64:

“He Surely Will”

CHAPTER 65:

He’s Gone Ahead

CHAPTER 66:

The Dream

CHAPTER 67:

As If He Knows Something

CHAPTER 68:

The Bargain

CHAPTER 69:

Reprieve

CHAPTER 70:

Almost There

CHAPTER 71:

A Good Thing

CHAPTER 72:

Change of Plans

CHAPTER 73:

“Just Watch”

CHAPTER 74:

The Golden Box

CHAPTER 75:

Forever

CHAPTER 76:

Peter’s Plea

CHAPTER 77:

Attack

CHAPTER 78:

All the Time in the World

CHAPTER 79:

The Last Moment

THE NEVER LAND

T

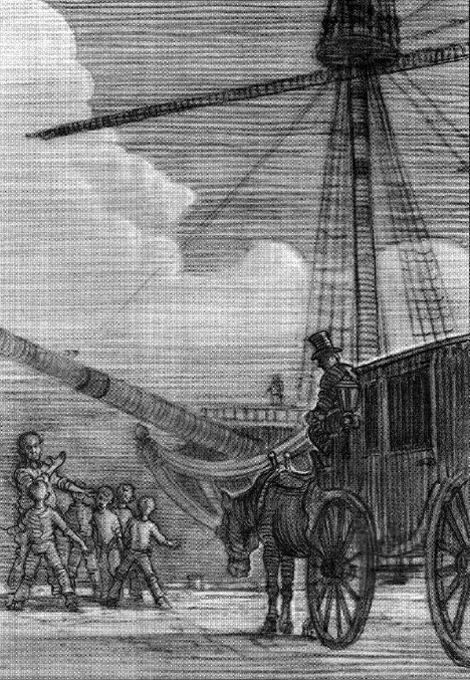

HE TIRED OLD CARRIAGE, puled by two tired old horses, rumbled onto the wharf, its creaky wheels

bumpety-bumping

on the uneven planks, waking Peter from his restless slumber. The carriage interior, hot and stuffy, smel ed of five smal ish boys and one largish man, none of whom was keen on bathing.

Peter was the leader of the boys, because he was the oldest. Or maybe he wasn’t. Peter had no idea how old he real y was, so he gave himself whatever age suited him, and it suited him to always be one year older than the oldest of his mates. If Peter was nine, and a new boy came to St. Norbert’s Home for Wayward Boys who said he was ten, why, then, Peter would declare himself to be eleven. Also, he could spit the farthest. That made him the undisputed leader.

As leader, he made it his business to keep his eye on things in general. And he was not happy with the way things were shaping up today. The boys had been told only that they were going away on a ship. As much as Peter didn’t like where he’d been living for the past seven years, the longer this carriage ride lasted, the scarier “away” sounded in his mind.

They’d set out from St. Norbert’s in the dark, but now Peter could see grayish daylight through the smal , round coach window on his side. He looked out, squinting, and saw a dark shape looming by the wharf. It looked to Peter like a monster, with tal spines coming out of its back. Peter did not like the idea of walking into the bel y of that monster.

“Is that it?” he asked. “The ship we’re going on?”

He ducked then, avoiding the hamlike right fist of Edward Grempkin. He was always keenly aware of where this fist was; he’d been dodging it for seven years now. Grempkin, second in command at St. Norbert’s Home for Wayward Boys, was a man of numerous rules—many of them invented right on the spot, al of them enforced by means of a swift cuff to the ear. He paid little attention to

whose

ear his fist actual y landed on; al the boys were rule-breakers, as far as Grempkin was concerned.

This time the fist clipped an ear belonging to a boy named Thomas, who had been slumped, half asleep, in the carriage next to the ducking Peter.

“OW!” said Thomas.

“Do not end a sentence with a preposition,” said Mr. Grempkin. He was also the grammar teacher at St. Norbert’s.

“But I didn’t … OW!” said Thomas, upon being cuffed a second time by Grempkin, who had a strict rule against back talk.

For a moment, the carriage was silent, except for the

bumpety-bump.

Then Peter tried again.

“Sir,” he said, “is that our ship?” He kept an eye on the fist, in case

ship

turned out to be a preposition.

Peter was thinking about trying to run away, but he didn’t know if that was possible—to run away from “away.” In any event, he didn’t see much opportunity for escape; there were sailors and dockhands everywhere. Carts and carriages. Near the back of the ship, fancily dressed people boarded via a ramp with a rope handrail. Toward the bow, some pigs and a cow were being led up a steep plank, fol owed by commoners dressed more like Peter and his friends.

Grempkin glanced out the round window and grinned, but not in a pleasant way. There wasn’t a pleasant bone in his body.

“Yes, that’s your ship,” he said. “The

Never Land.

”

“What’s Never Land?” said a boy named Prentiss, who was fairly new to the orphanage and thus did not see the fist until it hit his ear.

”OW!” he said.

“Don’t you be asking stupid questions!” said Grempkin, who defined “stupid questions” as questions he could not answer. “Al you need to know is this ship wil be your home for the next five weeks.”

“Five weeks, sir?” asked Peter.

“If you’re lucky,” said Grempkin leaning out of the carriage now to study the sky. “If a storm doesn’t blow you halfway to hel .” He smiled again. “Or worse.”

“Worse than hel , sir?” inquired James.

“He means if the ship sinks,” said Tubby Ted, who had a gift for looking on the dark side, “and we wind up in the sea, swimming for our lives.”

“But I can’t swim,” said James. “None of us can swim.”

“I can swim,” Tubby Ted declared proudly.

“You can

float

,” corrected Peter. Even Grempkin cracked a smile at that, yel ow tooth stumps showing through chapped lips.

Peter looked down the wharf and saw a much nicer-looking and bigger ship, painted a shiny black. Its crew wore uniforms, unlike that of the

Never Land.

It, too, was being loaded and seemed ready to set sail. If it came down to choosing between the two ships …

“It don’t matter,” said Grempkin, brightly, his mood improving. “Swim, sink, float—the sharks wil take care of al you boys before you get a chance to drown.”

“Sharks?” said James.

“Big fish with lots of teeth,” said Tubby Ted. “They eat people.”

“What if there’s no people in the sea?” said Thomas. “What do the sharks eat then?”

“Whales,” said Tubby Ted. “But they like people better, and there’s plenty of people in the sea. Ships is always going down. I heard about one … OW!”

“That’s enough of your jabber,” said Grempkin, who had a rule against too much jabber.

The carriage pul ed to a stop beside the ship. As Grempkin and the boys climbed out, a thick, bald man in a grimy officer’s uniform thumped down the gangplank and approached the carriage.

“You Grempkin?” he said.

“I am,” said Grempkin. “And you are … ?”

“Slank. Wil iam Slank. First officer, second in command of the

Never Land.

” The man made a face as if he’d just bitten into a rancid prune. It occurred to Peter that Slank didn’t like being second in anything. “These are the orphans, then?”

“They are,” said Grempkin. “And you’re welcome to them.”

“I don’t care for boys,” observed Slank.

“Then you’l definitely not care for these,” said Grempkin.

“We’ve had boys on board before,” said Slank. “They was always stirring up the rats.”

The boys glanced at one another.

Rats?

“The thing to do,” said Grempkin, “is keep them disciplined.” To il ustrate, he shot his fist sideways, not looking where it was going. It struck Prentiss, who, being fairly new, had not yet learned that it was unwise to stand immediately to Grempkin’s right.

“OW!” said Prentiss.

“Sir,” said James, to Slank, “there’s rats on the ship?”

“Don’t you be playing with the rats!” said Slank, cuffing James on the ear. “They make a tasty treat when the food runs out.”

“The food runs out?” asked Tubby Ted, suddenly reluctant to take another step. “When?”

Slank slapped him across the ear and said, “After we eat

you.

”

Grempkin nodded approvingly, confident now that he was leaving the boys in good hands.

Peter scanned the area for a place to run and hide. He saw a supply store offering pul eys and hemp rope, some taverns—the Salty Dog, the Mermaid’s Song.

Mermaids?

Peter wondered. But everywhere he looked, there were sailors and dockworkers, rough men with rough hands. He wouldn’t get ten paces before one of them would col ar him, if Slank didn’t col ar him first.

“I’l be getting back to St. Norbert’s,” Grempkin said. He turned toward the coach, paused for a moment, then turned back and said, “You boys better watch out for yourselves.” In seven years, that was the nicest thing Peter had ever heard Grempkin say.

“Al right,” said Slank, as Grempkin turned back to the coach. “You boys get on board. We’re waiting for one more piece of cargo, and then we cast off.” Peter eyed the nicer ship down the wharf. Some soldiers were approaching it, carrying rifles with bayonets. The soldiers wore crisp blue uniforms and black, shiny boots. They walked on either side of a horse-drawn cart that carried a single trunk, black, done al around with chains and padlocks.

The boys hesitated, taking their first good look at the

Never Land.

It wasn’t as big as they’d expected, and it looked old and poorly kept—frayed ropes, peeling paint, barnacles and green slime climbing the hul from the waterline.

“Get a move on!” said Slank.

“I can’t swim,” whispered James.

“We’l be al right,” said Peter. “It can’t be worse than St. Norbert’s.”

“Yes it can,” said Tubby Ted. “The food runs out.”

“Sharks,” Thomas reminded them. “Rats.”

“We’l be al right,” repeated Peter, and he started up the gangplank, being the leader, but stil thinking about finding a way to escape before the ship set sail.

THE SECOND TRUNK

N

OT FAR DOWN THE WHARF from the Salty Dog and the Mermaid’s Song, two men toiled in a dark, dismal warehouse, its enormous doors open to the harbor and the ships that were preparing for departure.

“Are we done, then?” asked Alf, the bigger of the two. He had a nose wart the size and shape of a smal mushroom. “Because I could use some grog.” Alf, being a sailor, could always use some grog.

“Not yet,” said Mack. “Slank says we got one more to get aboard, this one over here.” Mack, a thin man, but as strong as any hand on the

Never Land,

had a tattoo of a snake’s head on his neck, the snake’s body disappearing into his sour clothes.

Mack pointed to a corner of the warehouse where a filthy canvas was draped over a bulky object. The two men trudged over. Mack grabbed a corner of the canvas and pul ed it off, revealing a common-looking trunk made of rough wood but held shut by thick chain and secured by two—no,

three

—padlocks.

Alf studied the trunk, frowning. “Ain’t this the trunk them soldiers brought in here this morning?” he asked.

“It looks like it,” said Mack. “But it ain’t. There was

two

trunks come in together. The black one got loaded onto the

Wasp

by them soldiers. Heavy as lead, it was. Then Slank pul s me aside and says he wants us, real careful-like, to put this one aboard the

Never Land.

He says, tie the canvas tight ’round it and walk it up the main gangway like it belong to one of the travelers. He says if we do this right there’s two bob more in our pay.”

“Apiece?” said Alf.