Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind (16 page)

Read Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind Online

Authors: V. S. Ramachandran,Sandra Blakeslee

Tags: #Medical, #Neurology, #Neuroscience

As the British immunologist Peter Medawar has noted, science is the "art of the soluble," and one could argue that the discovery of multiple specialized areas in vision makes the problem of vision soluble, at least in the foreseeable future. To his famous dictum, I would add that in science one is often forced to choose between providing precise answers to piffling questions (how many cones are there in a human eye) or vague answers to big questions (what is the self), but every now and then you come up with a precise answer to a big question (such as the link between deoxyribonucleic acid [DNA] and heredity) and you hit the jackpot. It 60

This little experiment may have interesting implications for day−to−day activities and athletics. Marksmen say that if you focus too much on a rifle target, you will not hit the bull's−eye; you need to "let go" before you shoot. Most sports rely heavily on spatial orientation. A quarterback throws the ball toward an empty spot on the field, calculating where the receiver will be if he is not tackled. An outfielder starts running the moment he hears the crack of a baseball coming into contact with a bat, as his how pathway in the parietal lobe calculates the expected destination of the ball given this auditory input. Basketball players can even close their eyes and toss a ball into the basket if they stand on the same spot on the court each time. Indeed, in sports as in many aspects of life, it may pay to "release your zombie" and let it do its thing. There's no direct evidence that all of this mainly involves your zombie—the how pathway—but the idea can be tested with brain imaging techniques.

My eight−year−old son, Mani, once asked me whether maybe the zombie is smarter than we think, a fact that is celebrated in both ancient martial arts and modern movies like

Star Wars.

When young Luke Sky−walker is struggling with his conscious awareness, Yoda advises, "Use the force. Feel it. Yes," and "No. Try not! Do or do not. There is no try." Was he referring to a zombie?

I answered, "No," but later began to have second thoughts. For in truth, we know so little about the brain that even a child's questions should be seriously entertained.

The most obvious fact about existence is your sense of being a single, unified self "in charge" of your destiny; so obvious, in fact, that you rarely pause to think about it. And yet Dr. Aglioti's experiment and observations on patients like Diane suggest that there is in fact another

being inside you that goes about his or her business without your knowledge or awareness. And, as it turns out, there is not just one such zombie but a multitude of them inhabiting your brain. If so, your concept of a single "I" or "self" inhabiting your brain may be simply an illusion11— albeit one that allows you to organize your life more efficiently, gives you a sense of purpose and helps you interact with others. This idea will be a recurring theme in the rest of this book.

The Secret Life of James Thurber

Is this a dagger which I see before me, The handle toward my hand'? Come, let me clutch

thee: I have thee not, and yet I see thee still. Art thou not fatal vision, sensible To feeling as to sight? or art

thou but A dagger of the mind, a false creation, Proceeding from the heat oppressed brain?

—

William Shakespeare

When James Thurber was six years old, a toy arrow shot accidentally at him by his brother impaled his right eye and he never saw out of that eye again. Though the loss was tragic, it was not devastating; like most one−eyed people he was able to navigate the world successfully. But much to his distress, in the years after the accident his left eye also started progressively deteriorating so that by the time he was thirty−five he had become completely blind. Yet ironically, far from being an impediment, Thurber's blindness somehow stimulated his imagination so that his visual field, instead of being dark and dreary, was filled with hallucinations, creating for him a fantastic world of surrealistic images. Thurber fans adore "The Secret Life of Walter Mitty," wherein Mitty, a milquetoast of a man, bounces back and forth between flights of fantasy and reality as if to mimic Thurber's own curious predicament. Even the whimsical 62

"You said a moment, ago that everybody you look

at seems to be a rabbit. Now just what do you mean

by that, Mrs. Sprague?"

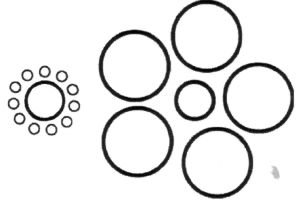

Figure 5.1

One of James Thurber's well−known cartoons that appeared in

The New Yorker.

Could Ms visual

hallucinations have been a source of inspiration for some of these cartoons?

By James Thurber, 1937, from

The New Yorker Collection.

All rights reserved.

cartoons for which he was so famous were probably provoked by his visual handicap (Figure 5.1).1

Thus James Thurber was not blind in the sense that you or I might think of blindness—a falling darkness like the blackest night sky, entirely devoid of moonlight and stars, or even a complete absence of vision— an unbearable void. For Thurber, blindness was brilliant, star−studded and sprinkled with pixie dust. He once wrote to his ophthalmologist:

Years ago you told me about a nun of the middle centuries who confused her retinal disturbances with holy visitation, although she saw only about one tenth of the holy symbols I see. Mine have included a blue Hoover, golden sparks, melting purple blobs, a skein of spit, a dancing brown spot, snowflakes, saffron and light blue waves, and two eight balls, to say nothing of the corona, which used to halo street lamps and is now brilliantly discernible when a shaft of light breaks against a crystal bowl or a bright metal edge. This corona, usually triple, is like a chrysanthemum composed of thousands of radiating petals, each ten times as slender and each containing in order the colors of the prism. Man has devised no spectacle of light in any way similar to this sublime arrangement of colors or holy visitation.

Once, after Thurber's glasses shattered, he said, "I saw a Cuban flag flying over a national bank, I saw a gay old lady with a gray parasol walk right through the side of a truck, I saw a cat roll across a street in a small striped barrel. I saw bridges rise lazily into the air, like balloons."

Thurber knew how to use his visions creatively. "The daydreamer," he said, "must visualize the dream so vividly and insistently that it becomes, in effect, an actuality."

Upon seeing his whimsical cartoons and reading his prose, I realized that Thurber probably suffered from an 63

extraordinary neurological condition called Charles Bonnet syndrome. Patients with this curious disorder usually have damage somewhere in their visual pathway—in the eye or in the brain—causing them to be either completely or partially blind. Yet paradoxically, like Thurber, they start experiencing the most vivid visual hallucinations as if to "replace" the reality that is missing from their lives. Unlike many other disorders you will encounter in this book, Charles Bonnet syndrome is extremely common worldwide and affects millions of people whose vision has become compromised by glaucoma, cataracts, macular degeneration or diabetic retinopathy. Many such patients develop Thurberesque hallucinations—yet oddly enough most physicians have never heard about the disorder.2 One reason may be simply that people who have these symptoms are reluctant to mention them to anyone for fear of being labeled crazy. Who would believe that a blind person was seeing clowns and circus animals cavorting in her bedroom? When Grandma, sitting in her wheelchair in the nursing home, says, "What are all those water lilies doing on the floor?" her family is likely to think she's lost her mind.

If my diagnosis of Thurber's condition is correct, we must conclude that he wasn't just being metaphorical when he spoke of enhancing his creativity with his dreams and hallucinations; he really

did

experience all those haunting visions—a cat in a striped barrel did indeed cross his visual field, snowflakes danced and a lady walked through the side of the truck.

But the images that Thurber and other Charles Bonnet patients experience are very different from those that you or I could conjure up in our minds. If I asked you to describe the American flag or to tell me how many sides a cube has, you'd maybe shut your eyes to avoid dis−

traction and conjure up a faint internal mental picture, which you'd then proceed to scan and describe. (People vary greatly in this ability; many undergraduates say that they can only visualize four sides on a cube.) But the Charles Bonnet hallucinations are much more vivid and the patient has no conscious control over them—they emerge completely unbidden, although like real objects they may disappear when the eyes are closed.

I was intrigued by these hallucinations because of the internal contradiction they represent. They seem so extraordinarily real to the patient— indeed some tell me that the images are more "real than reality" or that the colors are "supervivid"—and yet we know they are mere figments of the imagination. The study of this syndrome may thus allow us to explore that mysterious no−man's−land between seeing and knowing and to discover how the lamp of our imagination illuminates the prosaic images of the world. Or it may even help us investigate the more basic question of how and where in the brain we actually "see" things—how the complex cascade of events in the thirty−odd visual areas in my cortex enables me to perceive and comprehend the world.

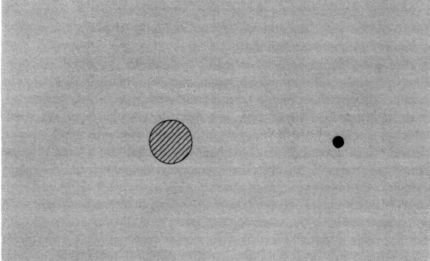

What is visual imagination? Are the same parts of your brain active when you imagine an object—say, a cat—as when you look at it actually sitting in front of you? A decade ago, these might have been considered philosophical questions, but recently cognitive scientists have begun to probe these processes at the level of the brain itself and have come up with some surprising answers. It turns out that the human visual system has an astonishing ability to make educated guesses based on the fragmentary and evanescent images dancing in the eyeballs. Indeed, in the last chapter, I showed you many examples to illustrate that vision involves a great deal more than simply transmitting an image to a screen in the brain and that it is an active, constructive process. A specific manifestation of this is the brain's remarkable capacity for dealing with inexplicable gaps in the visual image—a process that is sometimes loosely referred to as "filling in." A rabbit viewed behind a picket fence, for instance, is not seen as a series of rabbit slices but as a single rabbit standing behind the vertical bars of the fence; your mind apparently fills in the missing rabbit segments. Even a glimpse of your cat's tail sticking out from underneath the sofa evokes the image of the whole cat; you certainly don't see a disembodied tail, gasp and panic or, like Lewis Carroll's Alice, wonder where the rest of the cat is. Actually,

"filling in" occurs at several differ−

64

ent stages of the visual process, and it's somewhat misleading to lump all of them together in one phrase. Even so, it's clear that the mind, like nature, abhors a vacuum and will apparently supply whatever information is required to complete the scene.

Migraine sufferers are well aware of this extraordinary phenomenon. When a blood vessel goes into a spasm, they temporarily lose a patch of visual cortex and this causes a corresponding blind region—a scotoma— in the visual field. (Recall there is a point−to−point map of the visual world in the visual field.) If a person having a migraine attack glances around the room and his scotoma happens to "fall" on a large clock or painting on the wall, the object will disappear completely. But instead of seeing an enormous void in its place, he sees a normal−looking wall with paint or wallpaper. The region corresponding to the missing object is simply covered with the same color of paint or wallpaper.