Philip Jose Farmer (17 page)

Read Philip Jose Farmer Online

Authors: The Other Log of Phileas Fogg

Nemo had been hoping that they would reveal just how they had gotten loose, but they were keeping this a secret. He would find out someday; he swore to that.

“Besides,” Fogg said, “seeing him bound and gagged may disconcert whoever is at the other end. You may gag him now, Passepartout.”

“The clanging will undoubtedly awaken everyone on the

ship,” Fogg said. “And Fix, if he is a Capellean, will know what is transpiring. If anyone knocks, tell them you are frightened and won’t come out. Open the door for no one.”

“I understand,” Aouda said. Her voice was so soft, so lovely that Passepartout’s heart bounced as if on a trampoline. How could Fogg resist such a woman, who so openly adored him?

Aouda said, “The bell-like sounds will have to remain another of those mysteries of the sea.”

How prophetic her words were, though even she could not have foreseen that from that night there would be, not one, but two marine mysteries.

Passepartout crawled under the table and set the watch to activate within four minutes. He and Fogg climbed onto the table and stuck their fingers in their ears.

14

14

The three men found themselves aboard another ship.

This, however, was a small sailing ship, and the sun stood at an altitude indicating some time around nine in the morning. Fogg knew that this would place them somewhere in the Atlantic, probably between the 15th and the 30th meridians. After this hasty calculation, he had no time for scientific matters.

They had dropped a few inches from the air onto a small deckhouse near the forepart of the ship. They were so close to a mast projecting from the roof of the deckhouse that they could reach out and touch it. Near them, piled on the roof, was an untidy mass of canvas.

The only other human being in sight was on the deck about twenty feet away where he would be sure to be out of range of the distorter field. Pieces of white cotton stuck out of his ears, and he held a revolver.

The sailor did not shoot at once because he must have thought that the two armed men were Capelleans and the bound man was

the “slave” he had requested. It was true that he had expected only one Capellean and two bound men and a bound woman, but this may have further contributed to his astonishment. He could not grasp the idea that the situation had been changed.

Nemo, though painfully deafened by the nine clangors, nevertheless acted quickly. He straightened out and pivoted on his side, his long powerful legs coming around to strike both his captors across their ankles.

Passepartout, with the acrobat’s quickness of reaction, leaped into the air. Fogg, who should have foreseen this move, since he claimed that the unforeseen did not exist, was knocked off his feet. His shot went wide of the sailor and, of course, informed him that all was not as it was supposed to be. The sailor fired at Fogg, missed, perhaps because of the roll and pitch of the ship, and then ran along the deck toward the stern. Passepartout bounded down in pursuit, even though armed with only one of Nemo’s knives. He slipped, fell, rolled, and was back up on his feet at once.

Fogg had sprawled forward, and so was unable to keep Nemo from rolling off the roof of the deckhouse. He fell heavily on his side, and Fogg was after him a few seconds later. However, Fogg did not think there was much Nemo could do from then on. To make sure, he struck Nemo over the head with the butt of his revolver. Blood welled out from the wound, and a second later he suffered from another wound. The sailor, having turned once to fire at Passepartout, had missed. The bullet went downward and hit Nemo in his right arm.

Fogg left the limp and bleeding body and hastened after Passepartout. The sailor had taken refuge behind the rear of the

aft cabin, just forward of the wheel. Passepartout waited for Fogg at the companionway to the fore cabin. This could be entered by a sliding door which was already shoved to one side.

Since they had not been in a confined space, and the distorter had been, the clangings had not affected their eardrums as much as the previous time. Their hearing was restored enough so that they could hear each other if they put their heads closely together and shouted. Fogg told his comrade to wait there while he inspected the interior of the aft cabins. Perhaps there was another entrance at the other end of his deckhouse. He had to make sure that the sailor did not try a surprise attack by using this. Before reemerging from the doorway, he would give the password. Thus, if the sailor had entered the other end, and overcame or killed Fogg, he would not be able to take Passepartout unawares.

“I saw the upper part of the wheel over the top of this house,” the Frenchman said. “There was no one at it.”

“The ship seems to be deserted except for this Capellean,” Fogg said. “Very strange. But doubtless it can be explained. This seems to be a brigantine. And it’s going on the starboard tack.”

“Pardon, sir?”

“With the wind from the right. The jib and foremast staysails are set on the starboard tack. The ship is headed westward.”

“Jib? Foremast staysail, sir?”

“The headsails. At the front of the ship. The two middle sails, those triangular-shaped ones, attached to the long boom projecting from the nose of the ship. The lower fore-topsail, the fourth from the bottom of the main mast, seems to have been set, but its head has been torn, probably by the wind.

“The foresail and upper fore-topsail are missing. I would judge that they have been blown from the yards. The main staysail, the lowest of the three triangular sails attached between the two masts, is down. It’s that heap on the forward house. The aftersails have been removed. All other sails are furled, even the fore-and-aft sails. The main peak halyards, ropes for lowering and raising the sails, have been broken. Most of them are gone. Before the mainsail can be set, the halyards will have to be repaired. The seas are somewhat heavy, but the ship is not yawing much, that is, changing direction. But we can inspect the ship at a later time. I’m telling you this now so you’ll have some idea of what to do if I don’t return.”

That was not nearly enough for him to know what to do, Passepartout thought.

Fogg, holding the revolver ready, entered the cabin. The open door gave some light. There was a window on the bow end, but it had been covered with a piece of canvas secured by strips of plank nailed into the side of the cabin. The floor was wet, though there was no standing water. This could be accounted for by a heavy sea or rain having come in from somewhere. There was a clock without hands secured upside-down by the two nails to a partition. A table held a slate log and a rack—called by the sailors a fiddle—which kept dishes from sliding off. The rack held dishes but no food or drink was visible nor were there any knives and forks. A piece of canvas evidently used as a towel was on the rack.

Fogg also saw a stove and a swinging lamp.

He looked at the slate log, which would have been used by the chief to make notations while on deck.

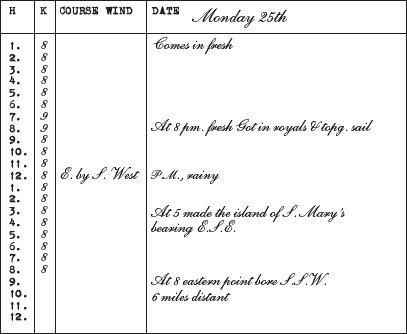

“H” stood for the hour; “K,” for knots. Though the log said it was for Monday the twenty-fifth, the date was nautical, not civil. The day would have started on noon of the twenty-fifth, not midnight. The twenty-fifth, for the ship, would end at noon of the twenty-sixth, after which it would be November twenty-sixth.

Today was November twenty-seventh. Something had happened at eight in the morning on the twenty-fifth, or a few hours later, to prevent the mate from continuing the log. When the record ended, the island of St. Mary’s was about six miles to the southwest.

On the port, or left, side of the cabin was the pantry. Fogg, entering it cautiously, found an open box holding moist sugar, a bag with several pounds of tea, an open barrel of flour, an open box of dried herrings, some rice and kidney beans in containers,

some pots of preserved fruit, cans of food, and a nutmeg. These were all dry.

Fogg went back into the mate’s cabin and looked around again. On the starboard side was a small bracket holding a tiny vial of oil for, he guessed, a sewing machine. This was still upright. If very heavy seas had been recently met, it would have been thrown to the deck. The bed was dry and showed no damage from water.

He looked under the bed and drew out the ship’s ensign and its private signal: WT. The letter “W” had been sewn on. Also under the bed was a pair of stout sailor’s boots, designed for bad weather but apparently unused. There were also two drawers. One held some pieces of iron and two unbroken panes of glass. The lower drawer held a pair of log sunglasses and a new log reel but no log line.

The next cabin, the last, was the captain’s. He doubted that the sailor was in it. If he had entered it, he surely would have made his presence known by now. However, Fogg entered it slowly, and he kept to the sides of the cabin after he got in. There was a skylight through which the sailor might shoot if he crawled onto the top of the deckhouse.

A harmonium, a reed organ, was by the partition in the center of the cabin. Near it was a number of books, mostly religious, by their titles.

A child’s high chair was on the floor along with a chest containing bottles of medicinals. A compass minus its card was on a table. A portable sewing machine was in a case attached to the bulkhead.

Under a bed, Fogg found a scabbarded sword. He removed

it, thinking that he could use it. It seemed to be of Italian make and had probably been an officer’s.

By the port side of the cabin was a water closet. Still cautious, because the sailor might be hiding there in ambush, Fogg looked within. Near the door was a damp bag. It looked as if it might have been wet by rain or spray entering through the half-covered port-hole on the opposite side.

Curious, Fogg entered the closet. He opened the bag and found ladies’ garments, all wet, inside. So the captain had been accompanied by his wife and small child.

The starboard side held two windows, also covered by canvas cut from a sail.

There were no signs of violence anywhere, and the cabin had no aft exit.

Fogg returned to the deck, though not without giving the password first. Passepartout said that the sailor had shown his head around the corner several times but had ducked back each time. Fogg told Passepartout what he had observed. He gave him the pistol, saying, “You hold that man with this. I’ll go back to check on Nemo and inspect the fore deckhouse.”

With the sword in hand, he walked slowly down the starboard side. Though his gait made him a better target for the sailor, he did not believe that it made him a good enough one. What with the wind and the motion of the ship, accuracy was not to be expected from a revolver at this range, Evidently the sailor, if he saw Fogg, had the same thoughts. No shots were fired.

Just before arriving at the fore deckhouse, Fogg went over to the port side. He looked around its corner. Nemo was gone.

Torn strips of sheet were evidence of Nemo’s great strength.

He had burst them apart with sheer muscularity. His boots lay by the strips.

Before he had returned on the starboard side, Fogg had looked down the port side. Nemo’s still figure had been on the deck. So, the wily fellow had waited until Fogg was out of sight, because he knew that Passepartout, watching for the sailor, would have his back to him.