Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (120 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Because her anchors have been torn away it is almost impossible for Robertson to duplicate Macdonough’s manoeuvre, but he is trying, swinging the frigate by putting a new spring on the bow cable—a daring feat under fire. Half-way round, she sticks fast at right angles to her enemy,

Saratoga

, whose newly freed guns can rake her from bowsprit to taffrail. At this point, Robertson’s crewmen refuse to do more. Why should they? they ask. Most of the British gunboats have not entered the battle. And where is the promised army support? Not a musket, not a cannon has been heard on the land side. Reluctantly, Robertson hauls down his colours.

Linnet

, under Daniel Pring, fights on for fifteen minutes more—the water rising so quickly in her lower deck that the wounded must be lifted onto chests and tables—then she, too, surrenders. Hicks, aboard

Finch

, stuck on a shoal, sees the flags go down and follows suit. Only the gunboats escape. The battle, which has lasted for two hours and twenty minutes, is over.

The senior British officers join Robertson and proceed to

Saratoga

to surrender their swords. As they step aboard, Macdonough meets them, bows. Holding their caps in their left hands and their swords by the blades, they advance, bowing, and present their weapons. Macdonough bows once more.

“Gentlemen, return your swords into your scabbards and wear them,” he says. “You are worthy of them.” He takes Robertson by the arm and walks the deck with his prisoners.

A twenty-one-year old Vermont farmboy, Samuel Shether Phelps, seeing the engagement has ended, takes a rowboat, pulls for

Saratoga

,

climbs onto the deck, almost slips in the blood, picks his way between the wounded and dead. Years later, when he is a state senator, he will be able to tell his children that the man he saw walking the deck, cap pulled low over his eyes, face and hands black with powder and smoke, was Commodore Thomas Macdonough, the legendary hero of the Battle of Plattsburgh Bay.

PLATTSBURGH, LAKE CHAMPLAIN, NEW YORK, SEPTEMBER 11, 1814

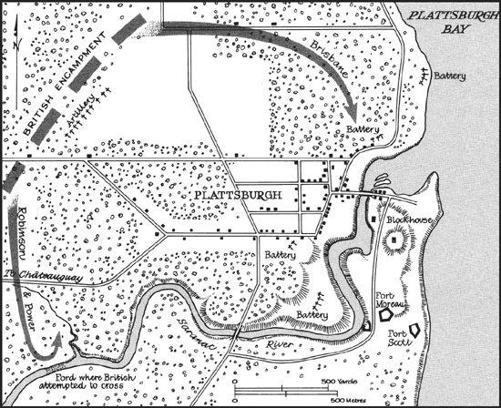

Major-General Frederick Philipse Robinson has been up since before dawn, fidgeting over the tardiness of his commander-in-chief. His task is to lead two brigades across the Saranac and then to assault the heights with artillery support. His men should have been at the ford by daybreak; Prevost has promised him that. But the order has not come and now it is almost eight. Why the delay?

Prevost heard from Downie as early as 3:30

A.M

. that the fleet was on its way, but the men are not yet in motion; instead, they have been told to cook breakfast. Something else troubles Robinson: the heaviest artillery has not yet arrived, nor are there batteries in place to receive the big guns. They cannot possibly be put in action before late morning.

From Cumberland Head Robinson hears the distant boom of cannon: Downie is scaling his guns, the signal that he is about to attack. An order comes from Prevost to attend at headquarters. The meeting takes an hour as Prevost reviews his plans. As Robinson turns to leave, the Governor General looks at his watch.

“It is now nine o’clock,” he says. “March off at ten.”

Clearly, Prevost expects the sea battle to go on all day. But as the two brigades move off in full view of the contest,

Preble, Finch

, and

Chubb

are already out of action. On Robinson’s left, Major-General Brisbane leads his brigade against the lower bridge, his flank protected by the water. Robinson’s force heads for Pike’s ford.

After a mile and a half, the troops are faced by a bewildering pattern of cart tracks leading into a thick wood. The army halts as the guides argue over the route. Finally the force retraces its steps and after an hour’s delay arrives at the river. Macomb’s deception has paid dividends.

Plattsburgh, September 11, 1814

From the bay comes the sound of cheering. A victory? By whom? Robinson dispatches an aide to find out. Meanwhile, he orders his men to rush the Saranac. They race down the bank and splash across the shallow ford in the face of heavy fire from four hundred American riflemen concealed on the far shore. The defenders scatter as the brigades form on the far side in perfect order. As Robinson rides forward to give orders for the attack, his aide returns with a message from Baynes, the adjutant-general:

I am directed to inform you that the “Confiance” and the brig having struck their colours in consequence of the frigate having grounded, it will no longer be prudent to persevere in the service committed to your charge, and it is therefore the orders of the

Commander of the Forces that you will immediately return with the troops under your command.

Robinson and his fellow general Manley Power are thunderstruck and chagrined, but they give the order to retire.

Major-General Brisbane tells Prevost that he will carry the forts in twenty minutes if given permission, but Prevost will not grant it. He knows that even if he does seize the redoubts he cannot hold the ground while the lake remains under American control. With the American militia rushing to the colours and reinforcements on the way, the enemy can sail down Champlain and cut off his rear. The roads are in dreadful condition, winter is approaching, his lines of supply and communication are stretched thin.

Prevost has also intercepted a letter from a Vermont colonel to Macomb announcing that the recalcitrant governor of that state, Martin Chittenden, is marching from St. Alban’s with ten thousand volunteers, that five thousand more are on their way from St. Lawrence County, New York, and four thousand from Washington County. Almost twenty thousand men! Prevost sees himself surrounded by a guerrilla army of aroused civilians lurking in the woods, blocking the roads, stealing into his camp under cover of night, demoralizing his men, scorching the earth, murdering stragglers. What he does not know is that the letter is a fake. Macomb has outwitted him by an old ruse. Has Prevost forgotten that Brock used an identical forgery to convince Hull, at Detroit, that he was surrounded by thousands of Indians?

The Governor General moves his army back so swiftly that it reaches Chazy before Macomb realizes his adversaries have departed. He cannot know it, but even at this moment the British are facing another setback at Baltimore. Here, in a vain attack, Ross meets his death and a poetic young lawyer named Francis Scott Key, watching the rockets’ red glare over the embattled Fort McHenry, is moved to compose a national anthem for his country to celebrate the sight of the Stars and Stripes flying bravely in the dawn’s early light to signal British defeat.

Robinson is sick at heart over Prevost’s “precipitate and disgraceful” move back to Canada. “Everything I see and hear is discouraging,” he writes to a friend. “This is no field for a military man above the rank of a colonel of riflemen.… This country can never again afford such an opportunity, nothing but a defensive war can or ought to be attempted here, and you will find that the expectations of His Majesty’s ministers and the people of England will be utterly destroyed in this quarter.”

And, he might add, across the channel in the Belgian city of Ghent, where the news from Lake Champlain will have its own effect on the long-drawn-out negotiations for peace.

THIRTEEN

Ghent

August–December, 1814

GHENT, BELGIUM, AUGUST 7, 1814

Down the cobbled streets of the ancient Flemish town this Sunday morning, past greasy canals and spiky guild houses, comes a minor diplomat with a very English name—Anthony St. John Baker, secretary to the British peace mission. He crosses the Place d’Armes, enters the Hôtel des Pays-Bas, asks for the American commission, is met by James Bayard’s secretary, George Milligan, who points him in the direction of the Hôtel d’Alcantara, a three-storey building, cracked and weatherbeaten, on the Rue des Champs. It is said to be haunted—so spooky that servants are hard to hire—but if so, the ghosts have fled the arrival of the five American plenipotentiaries who have leased it for the peace talks and who have given it the wry title of “Bachelor’s Hall.”

Bayard, the handsome Federalist senator from Delaware, is alone when Baker calls to invite the Americans to meet the following day with the British at his temporary lodgings in the Hôtel du Lion

d’Or. Why not meet here? Bayard asks innocently: an excellent room is available. But the Englishman will have none of it, refuses with exquisite politeness even to look at the room. The American, with equal civility, tells him that an answer will be forthcoming later in the day.

Thus are fired the opening shots in the long, weary diplomatic war that will be waged here in this ancient clothmakers’ town, to parallel the real war being fought four thousand miles away on the Canadian border. On this very Sunday morning, as the two diplomats spar over the choice of a meeting place, Gordon Drummond unmasks his cannon before Fort Erie and begins his futile week-long bombardment.

The four American negotiators (Jonathan Russell is out of town) meet at noon to discuss what John Quincy Adams calls “an offensive pretension to superiority” on the part of the British. By every rule of diplomatic etiquette, the British should come to

them!

Adams hauls out a heavy tome by Georg Friedrich von Martens, the German expert on international law, to prove this point. Bayard finds a case in Ward’s

History of the Law of Nations

where the British themselves had resisted a similar overture. Henry Clay urges that this assumption of superiority be resisted, but Albert Gallatin is not so sure; the Swiss-born ex-cabinet minister is not inclined to slow the negotiations with questions of ceremony.

The discussion drags on for two hours until dinner. Adams proposes that they agree to meet the British “at any place other than their own lodgings.” Gallatin suggests softening the phrase to “any place that may mutually be agreed upon.” It is the first of many occasions when the former secretary of the treasury will curb his colleagues’ irritability.

Thus the stage is set for five months of frustrating bargaining and much hair-splitting. The Americans have already spent a month in Ghent attending functions in their honour, bartering for lodgings, traipsing up and down the narrow streets sightseeing, gazing at the canals and the oils of the Van Eycks, lingering over wine and cigars (to Adams’s great displeasure), and, in the absence of the British,

sounding each other out on the peace terms. Surprisingly, the disharmony that existed in the last days in St. Petersburg has vanished. Adams, who once hoped never to deal with Bayard again, now finds him the best of companions.

The following day, at one, the Americans take the measure of the three British negotiators. Vice-Admiral Lord Gambier, the titular chairman, is pompous but genial, the epitome of the desk admiral who has seldom been to sea, a big man with an enormous glistening bald head surrounded by a frizzle of greying hair. He is vice-president of the British Bible Society, a fact that sits well with John Quincy Adams.

Dr. William Adams (no kin to John Quincy) is an Admiralty lawyer and, though he prides himself on his wit and humour, is a garrulous bore, his mind stuffed with legalisms, his tongue more cutting than witty. He is such a nonentity that it is said that Lord Liverpool, when questioned about him, could not remember his name.

Henry Goulburn, the youngest of the trio, is of different mettle. A confirmed Yankee-phobe who can scarcely conceal his dislike of everything American, he will struggle in the days ahead to curb his natural irritability in the interests of diplomacy. This thirty-year-old public servant is the real chairman of the British mission and the closest of the three to the British government.

After the usual professions of a sincere and ardent desire for peace (which neither side believes of the other), the meeting gets down to business. Goulburn, for the British, suggests four topics for discussion:

First, the question of impressment, the only stated reason for the war.

Second, the absolute necessity of pacifying the Indians by drawing a boundary line for their territory.