Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (64 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

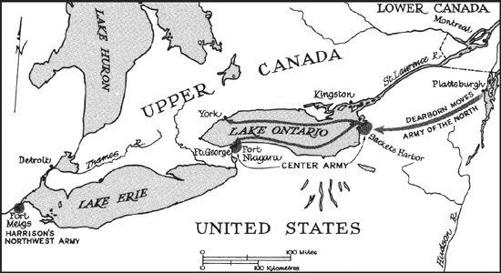

The lack of hospital supplies and proper food helped to bolster the sick list. In Canada, almost every item the army needed, from rum to new uniforms, came by ship from overseas. Every scrap of canvas, every yard of rope, every anchor, cannonball, bolt, cable, rivet came across the ocean by sail to Montreal. From there it was trundled by sleigh in winter or flatboat in summer to Kingston, York, Fort George, or Amherstburg. Troops on the Niagara peninsula, a thousand miles from the sea, were fed on pork from Ireland, flour from England, grog from the West Indies. Upper Canada was joined to the lower province by the most tenuous of supply lines—the St. Lawrence route. If the Americans could cut that lifeline at Kingston, the upper province would certainly wither and fall. That was the basic American strategy in 1812—a strategy foiled by Brock and Tecumseh. With the new campaign awaiting only the opening of the lakes, it remained the American strategy in 1813.

Three new armies threatened Canada. The Army of the North at Plattsburgh on Lake Champlain, only fifty miles south of Montreal, forced the British to keep the bulk of their troops in Lower Canada to meet the threat. The Army of the Center, at Sackets Harbor, Oswego, and the Niagara River, threatened Kingston, Fort George, and York. The Army of the Northwest, under William Henry Harrison, secure behind the ramparts of Fort Meigs on the Maumee, was poised to retake Detroit, cross the river, and threaten Fort Amherstburg and the valley of the Thames.

John Armstrong, the new American Secretary of War, worked out the strategy. In order to field enough men to cut the Canadian lifeline he planned to move the Plattsburgh army secretly to Sackets Harbor. There, the combined forces under Major-General Henry Dearborn would, with the co-operation of the newly built American fleet, sweep across the lake and capture Kingston. Harrison, on the American left flank, was ordered to create enough diversions to prevent British reinforcements being sent east to resist the American thrust. But he was told not to attack Canada until a second American fleet, under construction on Lake Erie, was ready to seize control of the waters. The Americans had learned an expensive lesson in 1812: he who controls the lakes controls the war.

On both Lake Erie and Lake Ontario, the two sides were engaged all winter in a frantic shipbuilding contest. The British were hammering together two big frigates for Lake Ontario, one at Kingston, another at York. The Americans were rushing their Lake Ontario fleet to completion at Sackets Harbor. The British had another big

ship on the ways at Amherstburg, preparing for the coming struggle for Lake Erie. The Americans, who had had no vessels on Erie in 1812, were building an entire fleet at Black Rock and at Presque Isle.

Time was of the essence. The side that got its ships into the water first could control the lake. So delicate was the balance of power that whoever managed to destroy one or more enemy vessels might easily gain naval superiority.

If Kingston were to be captured, the British supply line to Upper Canada cut, and the fleet in the harbour destroyed, the war was as good as over. With undisputed control of Lake Ontario, the Americans could easily invade the upper province, then mount an attack down the St. Lawrence to seize Montreal. And yet, as spring approached both Commodore Isaac Chauncey and Major-General Dearborn began to have second thoughts about the projected attack on Kingston. Dearborn became convinced that between six and eight thousand troops were guarding the Canadian stronghold, including three thousand regulars. This was a monumental overestimate. The regulars did not exceed nine hundred and were supported by only a handful of militia. Yet such was Dearborn’s apprehension that he daily expected an attack on his base at Sackets Harbor. Chauncey, while disputing Dearborn’s figures, believed that the British knew of the American plans and would be prepared for any attack. This extraordinary failure of nerve set the tone for the campaign to follow.

Somehow, the two cautious commanders managed to persuade themselves that an attack on York would be just as effective and more certain of success. In short, they decided to lop off a branch of the tree rather than attack the trunk—a total reversal of the original American plan, which had insisted on the capture of Kingston before any assault on York or Fort George.

Still, there was

something

to be gained at York, for the Americans had no corner on myopia. Instead of concentrating their activities at Kingston, the British had foolishly decided to build one of their big ships at York’s unprotected harbour. That ship,

Isaac Brock

, and one or two smaller vessels, would be the object of the combined naval and military assault on the Upper Canadian capital. If the ships at York could be captured intact and transferred to the American navy, Chauncey would have control of the lake. After that, the main British bastion on the Niagara—Fort George—could be seized, the peninsula rolled up, and, finally, Kingston invaded.

Changing U.S. Strategy, Winter, 1813

Both commanders succeeded in convincing the Secretary of War and each other that this strategy would be the most effective for the spring of 1813. Both waited impatiently for the ice to break in the lakes. On April 18, Sackets Harbor was open, freeing the fleet, but a week went by before the ships set sail. Finally, on the evening of April 26, after a rough passage, the invasion force appeared off the Scarborough bluffs not far from Little York. The campaign of 1813 was under way.

ONE

The Capture of Little York

April 26–May

2, 1813

While its left wing holds fast on the Lake Erie front, the main American army, under Major-General Dearborn, embarks at Sackets Harbor to attack York, the capital of Upper Canada. Its purpose is twofold: to seize the two large warships in Toronto harbour, add them to its fleet, and thus gain naval superiority on Lake Ontario; and to destroy the garrison troops. That accomplished, the American command is convinced that Fort George, and later Kingston, will fall before a combined land and water attack, and Upper Canada will be out of the war

.

YORK, UPPER CANADA, APRIL 26, 1813

The Reverend Dr. John Strachan, schoolmaster, missionary, and chaplain of the York garrison, is in the act of drafting a letter to his mentor, the Reverend James Brown, professor at Glasgow University.

“I have just received a letter from my Brother sealed with black,” Strachan has written. “My mother … is no more.… My mind is

strong to bear misfortune tho it sometimes recoils upon itself. My heart would break before a Spectator knew I was much affected. I think that I can bear calamity better than others.…”

Calamity of another kind is lying just beyond the eastern bluffs, but the stoical clergyman is not aware of it. Having unburdened himself, he changes the subject, suggests publication of a joint volume of sermons, then suddenly breaks off, blotting the paper, as an express rider, galloping through the muddy streets, shouts out his news.

“… I am interrupted,” Strachan writes. “An express has come in to tell us that the enemy’s Flotilla is within a few miles steering for this place all is hurry, and confusion, and I do not know, when I shall be able to finish this.…”

But finish it he will, some six weeks later, making a fair copy of the blotted draft, which he carefully saves, as he saves everything—his letters, first and final copies, poems, manuscripts, journals, sermons, and polemics—for the Reverend Doctor rejoices in the conviction that he is marked for posterity. In that he is right, for coming events will help propel him into a position of leadership. John Strachan will shortly become the most powerful man in Upper Canada aside from the Governor himself, the acknowledged leader of the ruling elite soon to be known as the Family Compact.

Before he puts his pen aside, Strachan adds one more sentence:

“I am not afraid, but our Commandant is weak.”

It is a revealing remark by a man who prides himself on having conquered all emotions, or at least their outward manifestations—fear, passion, grief—and who sees himself also as a military expert, an armchair general. He has pronounced views on almost everything, thinks nothing of dispatching long letters of military advice to professional soldiers. An amateur tactician, he is an opponent of the defensive strategy prescribed by the British war office and carried out by the cautious and conciliatory commander-in-chief, Sir George Prevost, Governor General of Canada.

“Defensive warfare will ruin the country,” declares Strachan. Did not Isaac Brock, his dead hero, believe that offence was the best defence? In the pugnacious clergyman’s view, Major-General Sir

Roger Hale Sheaffe, Brock’s successor in charge of the forces of Upper Canada, is weak and vacillating. As for the navy, its officers are “the greatest cowards who ever lived.” Strachan reserves his praise for the civilian soldiers who make up the militia, especially the York Volunteers, who number among their officers a commendable sprinkling of his own proteges. In Strachan’s view, the militia “are capable of doing more than the bravest Veterans.”

This is bunkum. The militia fought bravely enough at Queenston Heights; but many are badly trained—in many cases not trained at all—and have a dismaying habit of quitting their duty for the harvest fields.

Yet such are Strachan’s persuasive powers that he will one day convince the country, against all evidence, that these civilians are the saviours of Upper Canada. It is an attractive myth, powerful enough to unite a province. A century after the war, it will still be believed.

Strachan, then, is the catalyst that will make this grubby little war appear as a great national enterprise, in which an aroused and loyal populace almost single-handedly repulses a corrupt and despotic invader. Even before war threatened, he understood his duty: to save Upper Canada from the Americans. For in Strachan’s eyes they are “vain and rapacious and without honor,” obsessed with “licentious liberty.”

That is also the view of the Loyalists, those American Tories who moved into Canada after the Revolution and who must continue to justify that decision by rejecting all republican and democratic values. Strachan believes as implicitly in the British colonial system as he believes in the Church of England. A cornerstone of his faith is the partnership of Church and State, especially in matters of education—a useful tool to combat republicanism. He both despises and fears the incursion of Methodism, an alien cult from below the border, “filling the country with the most deplorable fanaticism.” He is equally aghast at the number of American settlers pouring into the province from the border states, bringing with them—in his view—an irreligious and materialistic way of life.

He is a man of many convictions. If the stocky figure in clergyman’s black, moving across the mud-spattered cobbles of Little York seeking more news of the Yankee fleet, is subject to doubts, he keeps them concealed behind a dour mask. At thirty-five he is not unhandsome—a black Scot with a straight nose, a firm cleft chin, and drooping eyes—a little sad, a little haughty. He is beyond argument the most energetic man in town, if not in the province, and, as events are about to prove, one of the most courageous. He teaches the chosen in his own grammar school, runs his parish, presides at weddings, funerals, christenings, and military parades, pokes his nose regularly into government, and manages a prodigious literary output: textbooks, newspaper articles, sermons, an emigrant’s guide, moral essays, and an effusion of indifferent poetry—sonnets, quatrains, lyrics, odes—even an autobiography, set down at the age of twenty-two.

The war has hardened his attitudes. To him it is a just war, one that Christians can prosecute with vigour and a clear conscience: “The justice of our cause is … indeed half the victory.”

He is not alone in this conviction. Aboard the tall ships lurking outside the harbour, bristling with cannon, other men, equally purposeful, are preparing for bloody combat; and their leaders are as certain as John Strachan that their cause is just and that the God of battles stands resolutely in their ranks.