Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (72 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Her exhausting odyssey is even more baffling because it is undertaken on the most tenuous of evidence—an unsubstantiated rumour, flimsy as gossamer, nothing more. On June 21 the Americans have made no firm plans to attack De Cew’s. Even Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Boerstler, the man chosen to lead the eventual assault, does not know of it until the afternoon of June 23.

Who are these Americans in Queenston on June 21? They must be Chapin’s guerrillas, for the regular troops have been called back to Fort George for fear of being cut off. Yet Chapin, by his own statement, knows nothing of any attack on De Cew’s—will not hear of it until orders are issued on June 23.

Yet

something

is in the wind. Has someone whispered a warning in Mrs. Secord’s ear? Who? It is not in her interest to give her source. News travels on wings here on the Niagara frontier. Who knows what damage might be done if Laura revealed what she knew? Her invalid husband and children could easily be the subject of revenge in this peninsula of tangled loyalties.

Like everybody else who has lived along the border, the Secords have friends on both sides of the line. Before the war people moved freely between the two countries, buying and selling, owning land, operating businesses without regard to national affiliations. Chapin himself was a surgeon in Fort Erie before he helped to found the town of Buffalo. His men are virtual neighbours; the Secords would know most of them. It may be that in later years, when the past becomes fuzzy, Mrs. Secord simply cannot remember the details of her source, though she seems to remember everything else. It is equally possible that she refuses to identify her informant to save him and his descendants from the harsh whispers and bitter scandal of treason.

FORT GEORGE, UPPER CANADA, JUNE 23, 1813

Henry Dearborn is in a bad way. Cooped up in Fort George by a numerically weaker adversary and, in his own words, “so reduced in strength as to be incapable of any command,” he has been humiliated

by the continuing assaults on the outskirts of his position. Dominique Ducharme’s Caughnawagas have just attacked a barque on the Niagara within sight of the fort, killing four American soldiers, wounding seven more, and escaping into the maze of trails that veins the forests along the frontier. It is too much. He has tried to excuse the reverse at Stoney Creek as a “strange fatality,” a pomposity which so exasperates the Secretary of War that he hurls the remark back at him in an acid letter that deplores

“the two escapes of a beaten enemy.”

Armstrong rubs Dearborn’s nose in it by underlining the words.

The ailing general knows he must do something to restore his shattered reputation. Why not a massive excursion to wipe out the Bloody Boys? He has only just learned that FitzGibbon has made his headquarters at the De Cew house. Five hundred men and two guns guided by Chapin and his marauders ought to do the job.

The details are handled by his new second-in-command, Brigadier-General John Boyd, who has replaced the ponderous politician Morgan Lewis but is no more popular than his predecessor. Winfield Scott has little use for this former soldier of fortune, while Lewis, who is not unbiased, believes him to be a bully and a posturer. Lewis has cautioned against just the sort of attack that Boyd and Dearborn now contemplate.

The command at Fort George is, in fact, rife with petty jealousies. There is little love lost between Dr. Chapin, who will guide the expedition, and the officer chosen to lead it, Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Boerstler, a thirty-five-year-old regular from Maryland who clearly despises the self-appointed civilian guerrilla. Yet of the two, the surgeon appears to be the more warlike. The sallow-faced Boerstler is uncommonly sensitive to imagined slights. Chapin, a lithe six-footer with a great beak of a nose, piercing blue eyes, and a long face bronzed by the sun, was once bitterly opposed to war with Britain—he still belongs to the Federalist opposition—but has since become an enthusiastic and unorthodox belligerent, known for his boldness as well as his ego. He cannot stand Boerstler, calls him “a broken down Methodist preacher.” Boerstler, on his part, has no use for Chapin, thinks him “a vain and boasting liar.”

Chapin is so put off by Boerstler’s appointment that he tries to get the high command to replace him, but Dearborn and Boyd decide to go with Boerstler, who has been embarrassingly touchy at being passed over on previous occasions and who has for days been pleading for a chance to lead an attack against the British.

Boerstler does not like Boyd and he does not like Winfield Scott, both of whom have been involved in what he considers slights to his abilities. Originally detailed by Lewis to lead the attack on Fort George, he was passed over at the last moment in favour of Scott. Just four days ago, Boyd replaced him on another assignment, again at the last moment—a decision that produced a heated scene between the two commanders. Chapin’s remonstrances are in vain. Neither Boyd nor Dearborn is prepared to slight the sensitive Boerstler a third time.

The expedition is hastily and imperfectly planned. No attempt is made to divert the posts at the other two corners of the defensive triangle while De Cew’s is being attacked. Nor is there any reserve on which Boerstler can fall back in case of disaster. The problem is a lack of men: half the army is too sick to fight. The shortage is so serious that officers are forced to turn out on night patrol, shouldering muskets like privates. Boerstler has been promised a body of riflemen—essential in the kind of bush fighting that is certain to take place—but these sharpshooters, having been placed on guard, cannot be relieved. He marches off without them.

Captain Isaac Roach, so sick he can scarcely draw his sword, volunteers to go on the expedition with his company in place of an exhausted friend, but he has grave doubts about the mission. He hands his pocketbook to an old comrade, Major Jacob Hindman.

“I have no doubt we shall get broken heads before my return,” says Roach, “and if so send my trunk and pocketbook to my family.”

His closest cronies, all members of Winfield Scott’s family of artillery officers, see him off. None has confidence in Boerstler. He is, in Roach’s opinion, “totally unfit to command.”

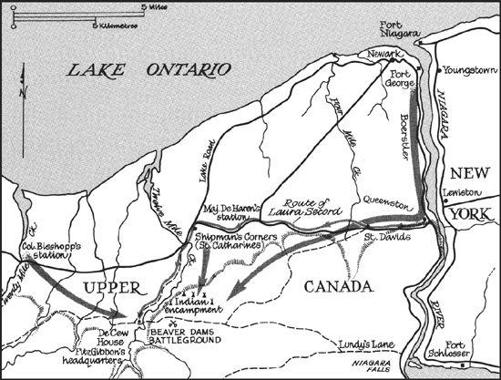

The column reaches Queenston an hour before midnight in absolute silence. Boerstler dispatches patrols to prevent any citizen escaping with news of the troops’ advance. (Laura Secord has now

been at FitzGibbon’s headquarters for more than twenty-four hours.) Lighted candles are prohibited, the men ordered to sleep on their arms. At daybreak the detachment moves on to St. Davids, where it surprises two of Dominique Ducharme’s Caughnawaga skirmishers. One is shot; the other escapes to warn Ducharme and his superior, Major De Haren, of the American advance.

Meanwhile the Americans are moving in column up the side of the Niagara escarpment, which the local settlers insist on calling a mountain. They halt at the top, move on for about a mile past an open field and into a defile bordered on both sides by thick woods. It is here that the Battle of Beaver Dams begins.

Each of the leading actors in the tangled drama that follows sees it in retrospect through the distorted lens of his own ego. Some three hours later, when it is all over and men lie dead, wounded, or captive, none can have a clear idea of exactly what happened. Yet each persuades himself that he alone is possessed of the truth.

François Dominique Ducharme sees it as a straightforward victory. He is forty-eight, a veteran of twenty-five years’ service in the western

fur country—a small, agile, incredibly tough skirmisher who now finds himself detailed to Upper Canada in charge of a band of Caughnawagas from the lower province. In his view, the decisions, the tactics, the victory are totally his—and those of his Indians. It is he, Ducharme, who persuades Major De Haren to allow him to move out of his original position in order to ambush the Americans in the woods. It is his Indians who kill every single one of Chapin’s advance guard at the outset of the battle. His allies, the Mohawks, who are on the far side of the road, flee at the first musket volley while Ducharme and his followers drive the Americans back to a coulee, surround them, and force a surrender. Or so Ducharme will remember and believe.

The Battle of Beaver Dams

To Charles Boerstler, the architect of the American defeat is Dr. Cyrenius Chapin. Boerstler believes that Chapin has led him into a trap, that he knows nothing about the country, has never been within miles of De Cew’s, and may well be a traitor since he

is a

former Federalist. Boerstler sees himself as a beleaguered commander, struggling against bad fortune, ordering his wagons and horses to the rear out of the enemy fire, forming up Chapin’s men himself in the unaccountable absence of their commander, concealing the wound in his thigh to avoid lowering the troops’ morale, and leading a gallant charge against the Indians in the woods—a charge made futile because of his lack of experienced sharpshooters. If only he could have reached that open field beyond the copse of beeches, where his musketeers might have used their parade-ground drill to oust the painted enemy!

If only!

As for Chapin, Boerstler sees him as a coward, reluctant to follow orders, taking cover with his men among the wagons in the gully at the rear, refusing to fight at all.

To Chapin, Boerstler is a blunderer who leans on him for information, boasts of seeking a personal battle with FitzGibbon (“Let me lay my sword against his”), and gratefully follows Chapin’s lead up to the pass in the escarpment. Chapin foresees the Indian ambush, warns his commander, and is in the act of driving five hundred natives through the woods when he is called back, against his will, by the timid and hesitant Boerstler who finally orders him to the

rear to select gun positions, with clear instructions not to pursue the enemy. Chapin must stand with his men at the guns and take fearful punishment while Boerstler and his troops move farther to the rear. Or so Chapin will come to believe.

One thing is clear: by noon the troops are exhausted. Boerstler, feeling hemmed in by the woods and the hidden Indians, has made the mistake of leading his men forward and keeping them too long exposed to heavy fire. The fault is not entirely his; the detachment was too small, the plans imperfect and hurried. The troops have been up since dawn, have marched eleven miles without refreshment, have fought for three hours under a blazing sun, have exhausted their ammunition. What is to be done?

Time will blur the memories of all the participants, but it does not matter, for at this moment James FitzGibbon appears on the scene carrying a white flag and demanding an American surrender.

FitzGibbon has actually been in the area for some time, having been alerted earlier in the morning by Ducharme’s scouts to the presence of an enemy column advancing toward his post. He has reconnoitred the battlefield and sent for his men, but the chances of capturing the Americans do not look good. He cannot depend on the Indians, who are coming and going on whim, some running off, others returning to the struggle; none is capable of forcing a surrender, and their leader, Ducharme, cannot speak English. At best, he thinks, the Americans will manage to untangle themselves and retire to Fort George. At worst, he and his small detachment of forty-four Bloody Boys may themselves be made prisoners. Finally, FitzGibbon decides upon a bluff, strides forward, white flag in hand.

Boerstler sends his artillery captain, McDowell, to meet him. The two parley. FitzGibbon resorts to the tried and true threat: he has been dispatched by Major De Haren to inform the Americans that they are surrounded by a superior force of British, that they cannot escape, and that the Indians, having met with severe losses, are infuriated to the point of massacre—a tragedy that can only be averted if Boerstler surrenders. Boerstler refuses. He is not accustomed, he says, to surrender to an army he has not seen.

FitzGibbon’s bluff has been called. There is no unseen army—only Ducharme and his Caughnawagas. Nonetheless, FitzGibbon boldly proposes that the Americans send an officer to examine De Haren’s force: that will convince them that the odds against them are overwhelming. Boerstler agrees but declares there will be no surrender unless he finds he is badly outnumbered. FitzGibbon then retires on the pretence that he must consult with De Haren who is, of course, nowhere near the scene. Instead, FitzGibbon runs into Captain John Hall, who has just ridden up with a dozen Provincial Dragoons. Hall agrees, if necessary, to impersonate the absent major.

Back goes FitzGibbon to report that De Haren will receive one of the American officers. Boerstler sends a subaltern who encounters Hall, believing him to be De Haren. Hall, thinking quickly, declares that it would be humiliating to display his force but insists it is quite large enough to compel surrender.

Boerstler, weak from loss of blood, asks for time to decide. FitzGibbon gives him five minutes, explaining that he cannot control the Indians much longer.

“For God’s sake,” cries Boerstler, “keep the Indians from us!” and, with the spectre of the River Raisin never far from his mind, agrees to surrender.