Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (87 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

He must move quickly if he is to move at all; otherwise Harrison will be at his heels, giving him no chance to prepare a defence on ground of his own choosing. And here Procter stumbles. Inexplicably, he has been told by his superiors

not

to retire speedily. “Retrograde movements … are never to be hurried or accelerated,” Prevost’s aide writes from Kingston. And De Rottenburg, at Four Mile Creek on Lake Ontario, believes that the enemy’s ships are in no condition to move after the battle—therefore Procter should take time to conciliate the Indians.

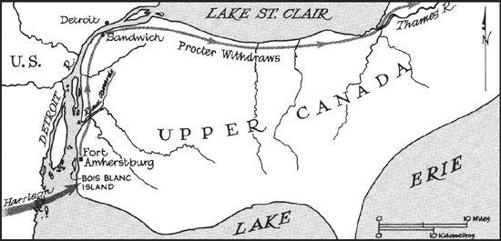

Procter, by his secrecy, has already wasted time. Almost a week passes before the promised meeting with the tribesmen. Even if they agree to move with the British, the logistics will be staggering. With women and children, their numbers exceed ten thousand. All must be brought across from Bois Blanc Island and from Detroit (which the British will have to evacuate) and moved up the Thames Valley. The women and children will go ahead of the army along with those white settlers who do not wish to remain under foreign rule. The sick must be removed as well—an awkward business—together with all the military stores. It is a mammoth undertaking, requiring drive, organizational ability, decision, and a sense of urgency. Procter does not display any of these qualities. And when he hears from De Rottenburg, he is given plenty of excuse to drag his feet.

He meets the Indians on September 18. Tecumseh urges that Harrison be allowed to land and march on Amherstburg. He and his Indians will attack on the flank with the British facing the front. If

the attack fails, Tecumseh says, he can make a stand at the River aux Canards, which he defended successfully the previous year. When Procter rejects this plan, Tecumseh, in a fury, calls him “a miserable old squaw.” At these words, the chiefs leap up, brandishing tomahawks, their yells echoing down from the vaulted roof of the lofty council chamber.

The time for secrecy is past. Procter unrolls a map and explains his position to the Shawnee war chief. If the gunboats come up the Detroit River, he points out, they can cut off the Indians camped on the American side of the river, making it impossible for them to support the British. Harrison can then move on to Lake St. Clair and to the mouth of the Thames, placing his men in the British rear and cutting off all retreat. Tecumseh considers this carefully, asks many questions, makes some shrewd remarks. He has never seen a map like this before. The country is new to him, but he quickly grasps its significance.

Procter offers to make a stand at the community of Chatham, where the Thames forks. He promises he will fortify the position and will “mix our bones with [your] bones.” Tecumseh asks for time to confer with his fellow chiefs. It is a mark of his flexibility that he is able to change his mind and of his persuasive powers that after two hours he manages to convince the others to reverse their own stand and follow him up a strange river into a foreign country.

Yet Tecumseh still has doubts. On September 23, after destroying Fort Amherstburg, burning the dockyard and all the public buildings, the army leaves for Sandwich. Tecumseh views the retreat morosely.

“We are going to follow the British,” he tells one of his people, “and I feel that I shall never return.”

The withdrawal is snail-like. It has taken ten days to remove all the stores and baggage by wagon and scow. The townspeople insist on bringing their personal belongings, and this unnecessary burden ties up the boats, causing a delay in transporting the women, children, and sick. Matthew Elliott, for example, takes nine wagons and thirty horses to carry the most valuable part of his belongings,

including silver plate worth fifteen hundred pounds. The organization of the military stores is chaotic. Entrenching tools, which ought to be carried with the troops, are shifted to the bottoms of the boats after the craft are unloaded to take them across the bar at the mouth of the Thames. The rest of the cargo is piled on top, making them difficult to reach.

Procter Withdraws

On the twenty-seventh, more than a fortnight after Barclay’s defeat, Major Adam Muir destroys the barracks and public buildings at Detroit and moves his rearguard across the river. All of the territory captured by Brock in 1812—most of Michigan—is now back in American hands. At five the same day, Lieutenant-Colonel Warburton marches his troops out of Sandwich.

That same evening, Jacques Baby, a member of a prominent merchant and fur-trading family and a lieutenant-colonel in the militia, gives a dinner for the senior officers of the 41st in his stone mansion in Sandwich. Tecumseh attends wearing deerskin trousers, a calico shirt, and a red cloak. He is in a black mood, eats with his pistols on each side of his plate, his hunting knife in front of it.

Comes a knock on the door—a British sergeant announcing that the enemy fleet has entered the river and is sailing northward near Amherstburg. Tecumseh, whose English is imperfect, fails to catch the import of the message and asks the interpreter to explain. Then he rises, hands on pistols, and turns to General Procter.

“Father, we must go to meet the enemy.… We must not retreat.… If you take us from this post you will lead us far, far away … tell us Good-bye forever and leave us to the mercy of the Long Knives. I tell you I am sorry I have listened to you thus far, for if we remained at the town … we could have kept the enemy from landing and have held our hunting grounds for our children.

“Now they tell me you want to withdraw to the river Thames.… I am tired of it all. Every word you say evaporates like the smoke from our pipes. Father, you are like the crawfish that does not know how to walk straight ahead.”

There is no reply. The dinner breaks up as the guests join the withdrawing army. Tecumseh has no choice but to follow the British with those warriors still loyal to his cause. By now these number no more than one thousand. The Ottawa and Chippewa bands have already sent three warriors to make peace terms with Harrison. The Wyandot, Miami, and some Delaware are about to follow suit.

In the days that follow, Henry Procter, obsessed by the problems of the Indians, abandons any semblance of decisive command. In 1812 the tribesmen were essential to victory; without them Upper Canada might well have become an American fief. Now they have become an encumbrance. Procter literally fails to burn his bridges behind him—an act that would certainly delay Harrison—because he believes that if he does so the Indians, who follow the troops, will think themselves cut off and abandon the British cause. To Lieutenant-Colonel Warburton’s disgust, he purposely holds back the army in order to wait for the Indians. He does not, however, give that reason to his second-in-command but merely says that the troops should rest in their cantonments because of wet weather.

Indeed, he tells Warburton very little. Nor does he stay with the army. Mindful of his pledge to Tecumseh to make a stand at the forks of the Thames, he dashes forward on a personal reconnaissance, leaving Warburton without instructions—an action his officers find extraordinary.

He cannot get the Indians out of his mind. Their presence haunts him; the promises wrung from him at the council obsess him;

Tecumseh’s taunts clearly sting. And there is something more: his own superiors have harped again and again on the necessity of placating the tribesmen. De Rottenburg has expressly told him that he must “prove to them the sincerity of the British Government in its intent not to abandon them so long as they are true to their own interests” (which, translated, means as long as the Indians are prepared to fight for the British). Prevost has ordered him to conciliate the Indians “by any means in your power”—promising them mountains of presents if they will only follow the army. It is clear that the high command, taking its cue from the evidence of 1812, believes the Indians hold the key to victory; it does not occur to any that they may be the impediment that leads to defeat. There is also in the minds of Procter and his superiors another fear: if the Indians defect, may they not fall upon the British, destroy the army, and then swell the ranks of the invaders? Procter is caught in a trap: if he loses his native allies the blame will fall on him, but as long as Tecumseh is his ally, Procter is not his own man.

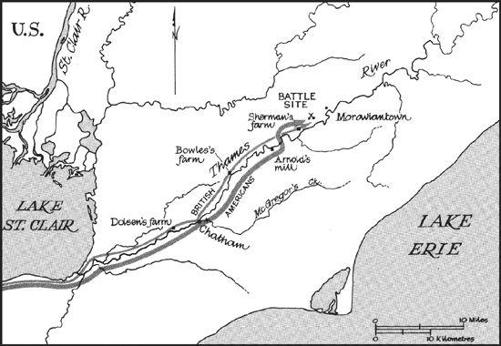

Retreat Up the Thames, September 27-October 5, 1813

He sends his engineering officer, Captain Matthew Dixon, upstream to the forks of the Thames at the community of Chatham.

Dixon’s report is negative: it is not the best place to make a stand. But something must be done, the General says; he has promised Tecumseh. Dixon is badgered into agreeing that the tiny community of Dover, three miles downstream from Chatham, is a slightly better position, but he cannot really recommend it. Procter seizes on this, appoints an assistant engineer, Crowther, to fortify the spot, ordering him to dig entrenchments and to place light guns at two or three points.

His heart is not in it. He and Dixon take off immediately for Moraviantown, twenty-six miles upstream, a much better position already recommended by the eccentric militia colonel and land developer, Thomas Talbot. In his haste, Procter does not think to inform his second-in-command, Warburton, marching up the valley with the army.

The General’s intentions are clear: the army will stand and fight at Moraviantown, not at the forks. But Henry Procter will always be able to say he kept his promise to Tecumseh.

FRENCHTOWN, RIVER RAISIN, MICHIGAN TERRITORY, SEPTEMBER 27, 1813

As the British fire the public buildings in Detroit and move back into Canada, twelve hundred mounted Kentucky riflemen, led by the fiery congressman, Colonel Richard Johnson, gallop along the Detroit road to reinforce Harrison’s invasion army. Here they pause at the site of their state’s most humiliating defeat to find the bones of their countrymen still unburied and strewn for three miles over the golden wheatfields and among the apple orchards.

The grisly spectacle rekindles the volunteers’ thirst for revenge. Here, on a bitterly cold day the previous January, Procter’s Indians struck down the flower of Kentucky, massacring them without quarter, butchering the wounded, burning some alive after putting the torch to buildings, holding others for ransom.

Remember the Raisin!

is the only recruiting cry needed in the old frontier commonwealth. Kentucky now has more men under arms than any state in the Union.

The regiment halts to bury the dead. Captain Robert McAfee writes in his diary that “the bones … cry aloud for revenge.… The chimneys of the houses where the Indians burnt our wounded prisoners … yet lie open to the call of vindictive Justice.…” The scene is rendered more macabre that night by a tremendous lightning storm “as if the Prince of the Power of the air … was invited at our approach to scenes of Bloodshed.…”

Its task completed, the regiment rides on toward Detroit, where William Henry Harrison awaits them. Most have been in the saddle since mid-May, after Harrison had asked for reinforcements to relieve Fort Meigs. Richard Johnson was only too eager to answer the call. Without waiting for War Department approval, he issued a proclamation:

Fort Meigs is attacked—the North Western army is Surrounded … nobly defending the Sacred Cause of the Country.… The frontiers may be deluged with blood; the Mounted Regiment will present a Shield to the defenseless.…

Every arrangement shall be made—there shall be no delay. The soldier’s wealth is HONOR—connected with his Country’s cause, is its Liberty, independence and glory, without exertions Rezin’s [sic] bloody scene may be acted over again and to permit [this] would stain the national character.…

Such purple sentiments spring easily from Richard Mentor Johnson’s pen. At thirty-two a handsome, stocky figure with a shock of auburn hair, he has made a name for himself as an eloquent, if florid, politician. The first native-born Kentuckian to be elected to both the state legislature and the federal congress, he is a crony of Henry Clay and a leading member of the group of War Hawks who goaded the country into war. Like so many of his colleagues, he is a frontiersman by temperament, reared on tales of Indian depredations. His family were Indian fighters by inclination as well as of necessity. He has heard from his mother the story of one siege, when, as she was running from the blockhouse for water, a lighted

arrow fell on her son’s cradle. Fortunately for Richard Johnson it was snuffed out.