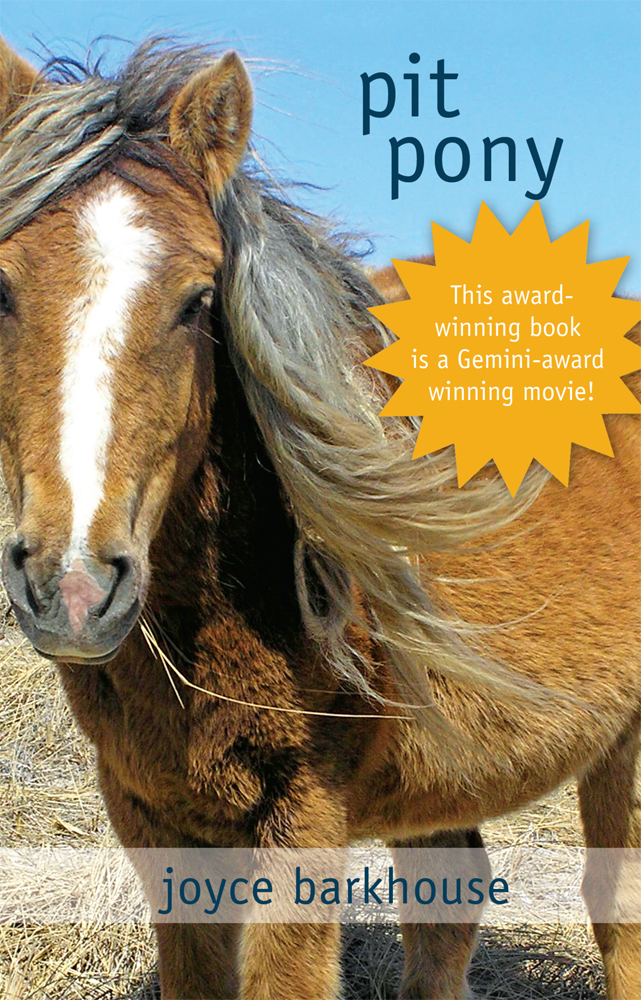

Pit Pony

Authors: Joyce Barkhouse

Tags: #JUVENILE FICTION / Historical / General, #JUVENILE FICTION / Social Issues / Friendship

Pit Pony

by

Joyce Barkhouse

Formac Publishing Company Limited

Halifax

To my two Janets

Chapter 1

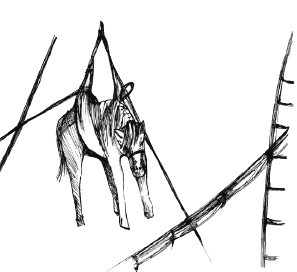

The wild horse screamed as its feet left the deck of the schooner. Then its body hung, limp and helpless in the sling under its belly, as it was winched ashore.

A crowd had gathered on the wharf to witness the spectacle of wild horses captured on far-off Sable Island, and brought to Nova Scotia to work in the coal mines of Cape Breton.

Among the watchers, a small boy stood with hands clenched into fists, his face twisted with pity. Tears trickled down his pale cheeks. His name was William Maclean but he was known around the coal mining town of Green Bay as “Wee Willie.” Sometimes he was called “Wee Willie the Whistler.”

Many of the Cape Breton miners had nicknames, like “Danny the Dancer,” “Stumpy Sam,” and “Freddie the Fiddler.” This was because so many of the Scottish families had names exactly the same. There were three William Macleans in Green Bay School, but Wee Willie was the one best known around town. When he wasn't at school he could usually be found hanging around one of the livery stables, wanting to help with the horses.

In those days, back at the beginning of the twentieth century, horses were a part of everyday life. A coal mine could not operate without them. In Willie's town, many different breeds were for hire â fast, pretty Morgans for driving or riding horseback, and big, strong Clydesdales for pulling heavy loads. Pairs of matched white horses were hired for weddings, and blacks for funerals.

Wee Willie loved them all. In fact, when he was with horses he forgot about everything else. Too often, he came home for supper too late to help with the chores. On these occasions, his little sisters, Maggie and Sara, had to go to the town well for water. It was much too hard for them. They staggered home with the heavy tin pail between them, sloshing water against their long skirts. His older sister, Nellie, who had all the other household tasks to do, had to feed the hens, bring in the eggs, and carry in scuttles of coal for the kitchen stove.

Tonight, Willie was late again. Not until the last horse struggled to its feet on the slippery wharf did he realize the sun had almost set. He dashed a grubby fist across his eyes and started for home. He knew how angry his father would be. He would give Willie a thrashing and send him to bed without his supper.

Willie didn't mind the thrashing quite as much as he minded going to bed without his supper. The Maclean children, whose mother had died when Willie was six, didn't have as much to eat as some of the other families. His father, Rory Maclean, was a pit miner who worked with Willie's brother John in the Ocean Deeps Mine. He was a proud, stern man. He refused to charge at the Company Store. All the same, the family lived in a Company house, for the sake of cheap rent.

Willie lived on Sunny Row. Not a tree nor a flower grew along the dirt lane. The houses were all the same, shaped like rectangles with slanting roofs and square, small-paned windows. It was called Sunny Row because of a habit the men had of sunning themselves during the long afternoons of the brief, Nova Scotia summers. The miners' wives put wooden washtubs on the steps, and here the colliers sat when they came home from the pit, still black around the eyes with coal dust. They would soak their sore, tired feet in the warm water, and joke back and forth while they watched their children play ball or kick the can along the dusty street.

But now it was October. The days were short and the nights were cold. Willie should have been home from school long since.

He went around to the back of the house. As soon as he stepped into the porch he smelled supper.

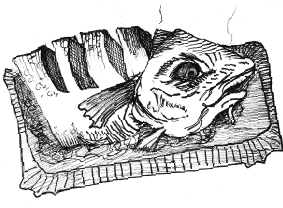

Ceann groppaig!

* His favourite dish! His sister, Nellie, was a good cook. And he would have to go to bed without a single mouthful.

*cown` graw` pik

He opened the door a crack and peeked in.

There they were, the whole family, six of them, seated around the table in the warm kitchen. His frowning, dark-mustached father sat at one end. The lamplight shone on the bright red heads of Nellie and his big brother John and made pale ovals of the faces of the dark-eyed little ones, Maggie and Sara. It reflected on the spectacles of his tiny old grandmother in her frilled white cap, as she peered over at him from her rocking chair. In the middle of the table sat the steaming ceann groppaig, a huge codfish head stuffed with a pudding made of rolled oats and flour and mashed cod livers.

All this, Willie saw in the flash of a second â and he was puzzled. What had happened? Usually the children ate first, because there weren't enough chairs to go around. When there was a

ceilidh

,* or when the minister came to call, then Nellie would borrow extra chairs from one of the neighbours. But tonight there was no guest.

*kay` lee

He opened the door a crack wider.

His father glared at him from under his bushy, black eyebrows. “Come in,” he ordered. “Shut the door. You're letting in a cold draft.”

Willie went in, hanging his head, shamefaced, and shut the door. Then the whole family shouted together, “Happy Birthday!”

He had forgotten. It was October 12, 1902, and he was eleven years old.

“Wash your hands and come to the table for blessing,” said his father.

Willie went to the dry sink and poured cold water from a bucket into the tin basin.

“How could you forget your own birthday?” scolded seven-year-old Sara, the youngest of the family, bouncing up and down in her chair.

“Hush! Bow your head for blessing,” said Rory Maclean.

As soon as Willie sat down, his father prayed, “God bless this house and this family. Teach them Thy ways, O Lord. May William learn, from this day on, to assume his full share of family responsibilities. Amen.”

He raised his head. The corners of his mustache lifted and he smiled at them all, including Willie. As if a black cloud had floated away and the sun had come out, they all smiled back. Rory Maclean picked up a knife and fork and prepared to serve the ceann groppaig. Willie felt a warm and happy glow inside.

“But where were you, Willie? Why were you so late?” Sara persisted.

“Mmm!” Willie savoured his first mouthful. “I was down by the waterfront to see the wild horses come in from Sable Island. Me and some other boys wanted to see them unloading.”

“And did you?” asked his big, red-headed brother, John, as he reached for a thick slice of homemade bread.

“We did,” said Willie. “And a sad sight it was, too. All them little wild, shaggy horses, scared to death. Some of them was cut and bleeding.”

“Why?” asked Sara.

“Because when they're aboard a schooner, they're tied by the legs and head so's they won't fall down or rear up in a storm,” explained Willie, between mouthfuls. Then he added, “It's a terrible thing to capture wild horses and make them go down the pits.”

“Maybe it won't do,” said his father. “Wild horses are apt to be fractious. But the Company can't find enough trained ponies to work the narrow seams.”

Sara tossed her blond pigtails. “Why....” she began, but her father interrupted impatiently.

“Be quiet, child, and eat up.” He looked over at Willie and frowned. “Willie needs to get home every night for his supper. If he don't, he'll stay little and stunted like a Sable Island pony. He's got to grow up big and strong to be a good miner.”

Willie was silent. He didn't want to grow up to be a miner. He wasn't like John who had never thought of being anything else. It had been a proud day for John when he had left school at fourteen and gone off to work with his father. He was considered a man now, with all a man's rights. No more thrashings for a boy who brought home a pay envelope.

Willie looked up at his father. His big, long-lashed brown eyes were troubled. “Maybe I won't be a miner,” he muttered.

His father put down his knife and fork.

Everybody stopped eating.

“Not be a miner! What will you be, then?”

Willie was trembling. “I like horses. Maybe I could be a blacksmith ... or ... something.”

“A blacksmith! How could a puny mite like you work at a forge and swing a great hammer?”

Willie hung his dark head, but he muttered, “'T'would be no harder than swingin' a pickaxe diggin' out coal in a mine.”

His father's face grew red with anger. “And where would the money come from to buy a shop and set you up with all your fancy ideas? We're a family of colliers, me and my father before me. I never thought to breed a lazy, good-for-nothin' brat who won't even do his share of chores. From now on, you get yourself straight home from school. If you're late for supper just once more, that's the end of school for you. You'll be down in the pits before you know what's happened to you.”

The children were silent, afraid of their father's hot temper. Little Maggie, the quiet, gentle one, began to cry. The birthday supper was ruined.

As soon as the dishes were cleared from the table Willie did his lessons, lighted his stub of candle, and crept away upstairs to bed.

Upstairs were two bedrooms and a wide, square hall. Willie and John slept together in a white-painted, iron bedstead in the hall. Now Willie crawled under the patchwork quilts. He blew out his candle, but for a long time he couldn't get to sleep. He was full of fear and anger.

He muttered to himself under his breath, “I'll never go down the mines. Never, never, never. I'm not goin' to live all my life in the black pits and get killed by an explosion, like my grandpa. I'll run away. Maybe I'll get aboard a ship. Maybe I'll live on Sable Island with the wild horses. Nobody could find me there.”

He knew a lot about Sable Island, one of the loneliest places in the world. It was fully described in the second chapter of his history book. He thought about it now and imagined he was there, riding free on the back of a wild horse over the sand dunes and through the long grasses, where the waves thundered in crashing white foam on the beaches.

But when he fell asleep, he dreamed of being lost, all alone, in the pitch dark tunnel of a coal mine.

Chapter 2

For the next few days Willie got home from school before his father. All the same he couldn't keep away from the Sable Island horses. As soon as school was dismissed, he was first out of the yard. He raced down the dirt road until he came to a path which led through a wood, across an open field, and down a hill to an old, abandoned farm.

Here, just outside the town limits, the horses were being kept in a pasture while they recovered from the rough voyage across the North Atlantic. The healthy, more docile ones were immediately broken to harness.

On his way to visit the horses, Willie passed a wild apple tree. Some fruit still clung to the branches. He filled his pockets with the best he could find. At the pasture gate, he hung over the bars and held out his hand with an apple on his palm. He whistled coaxingly. The horses only lifted their heads and stared at him.

One of the trainers called out, “Hey, you kid! Keep out of the paddock!”

“O.K.!” Willie shouted back. “But I can watch, can't I?”

“Sure. Just stay outside the fence.”

Willie couldn't linger long, but the next day, and the next, he was back again. The men, busy tending sores and bruises, or fitting horses to bit and bridle, paid little attention to him.

On the fourth visit, one of the small, shaggy mares responded to his call. She was a chestnut with a long, pale mane and a white blaze on her nose. She trotted up to the gate, stretched out her neck nervously, and ate the apple from his hand.

He gave her another, letting the cold juice mixed with her warm saliva trickle through his fingers. He looked into her brown eyes, and a wonderful, warm feeling flowed through his body. Right then, he knew he loved that horse more than anything. He wanted her for his own.

He looked up to see one of the horse trainers watching him. He recognized Big Mac from one of the livery stables. Big Mac stopped what he was doing and came over to talk to him.

“You're a good one with horses, Wee Willie,” he said, “but you needn't think you're working magic. That there mare's already been trained. She belonged to the lighthouse keeper's family. They called her âGem.'”

Willie stared in astonishment. “Honest? She's not a wild horse?”

Big Mac spit out a stream of tobacco juice. “Well, she was wild once, a'course. But horses are often caught and broke to the saddle on the Island. They're used to patrol the shores in case of shipwreck.”

Willie patted the mare's neck. “Gem,” he murmured. He rubbed her velvety nose, then he looked up at Big Mac. “Do you think she'd let me ride her?”

Big Mac's grin vanished. “Hey! Don't you dare try any tricks like that. If she threw you, it might scare the other horses. Just you keep out of this paddock, Wee Willie.”

“O.K.,” said Willie.

But he couldn't get the idea out of his head.

The next day, which was Thursday, Gem came trotting toward him as soon as she heard his whistle. He had saved a piece of molasses cookie from his lunch for her. He talked to her for a long time and rubbed her nose.

He was almost late for supper.

_fmt.jpeg)

* * *

On Friday afternoon, when Gem was nibbling a lump of sugar from his hand, Willie noticed that all the men had gone home. It had been a dark, drizzly day. Willie looked all around cautiously, but not a person was in sight.

“This is my chance,” he thought.

His heart began to thump with excitement.

“Come on, Gem,” he coaxed.

He felt in his pocket for the last sticky crumbs of sugar. He held out his hand and kept moving backward until the mare was standing sideways to the gate. She stretched out her neck over the bars, and lifted her upper lip for the treat.

Willie scrambled to the top bar and jumped. As he did so, the bar snapped under his weight with a loud crack. He landed astride the mare's back with a thump.

With a loud whinny of fright, Gem reared and bucked. Willie caught her long, tangled mane in his hands and hung on. Gem galloped off in a wide circle. As she came around to the gate with the broken bar, she gathered her legs beneath her and jumped.

Willie fell to the ground. For a moment he lay half-stunned. Then he scrambled to his feet.

Too late!

He could hear the thud of Gem's hooves fading away into the distance.

He stood frozen. The horses in the paddock snorted and stamped their hooves. They could escape, too! Instantly, Willie came alive. He pulled out the bottom bar and placed it on top.

He ran up the hill, across the open field, and into the woods where Gem had disappeared. He could see her tracks in the soft soil of the path. He stopped and whistled a long, shrill call.

Nothing happened.

It was very still inside the wood. A bluejay called, “Thief! Thief!” A sob caught in his throat. Where was that horse? He ran on, following her tracks.

The path ended, and he came out on the road. Here, there were so many horse droppings and hoofprints, it was impossible to pick out Gem's tracks. Still Willie ran on, into country where he had seldom been before. On either side of the road were rocks and stunted spruce trees, with here and there patches of barren, boggy soil covered with brown reeds and grasses.

He was out of breath and panting. Every little while, he stopped to whistle and call, “Gem! Gem! Come, Gem!”

His head hurt. He put up a hand under his grey, woollen cap and felt a lump as big as an egg. He must have landed on a rock when he fell from Gem's back.

It began to rain. Soon, it would be really dark. In the distance came the shrill sound of the siren at the colliery. The end of the shift! His father would be starting for home.

Willie stopped running and stood still. “Even if I turn back and run all the way, I can never get home first!”

He had said the words out loud but there was no one to hear. He felt hopeless and helpless. What could he do? Should he go back and not tell anybody what had happened? Maybe the stablemen would think Gem had escaped by herself. Anyway, maybe he wouldn't try to find Gem. Maybe the little mare was happy running free. Gem could find shelter in the woods from the storms of winter. But what about food? On Sable Island, it was said that the fierce winds swept the snow away from the tall grasses, but in Nova Scotia, sometimes the snow piled up as high as the eaves on the houses.

Willie walked slowly on. He didn't know what to do. Maybe Gem would be all right, but what about himself, Willie Maclean? His father would be furious if Willie told the truth about how he had tried to ride Gem, and how she had jumped the broken gate. If Willie refused to say what happened, he would be even more furious.

“Pa never goes back on his word. He's going to take me out of school and make me go down the pits,” Willie muttered to himself.

“If Mama was alive she wouldn't let him do this to me. She wouldn't!”

He tried to remember what his mother looked like but it was five years now since she had died, in pain, of some terrible disease. He could hardly remember her pale face, framed in red hair, but he could remember her smile. He remembered how she had looked at him with love and pride in her blue eyes.

“You may not grow up to be a big man, Willie,” she had said once, “but you have lots of brains. You study hard at school and you can be ... well, you can be whatever you want to be.”

He always treasured those words in his heart. His mother had loved and protected him.â¦Well, Nellie loved him, too, but she never stood up for him against their father. Nellie was scared. She liked things to be quiet and peaceful. Tears mixed with the rain beating against Willie's face. A sharp gust of wind blew his cap off. It went rolling ahead of him and stopped in a puddle. As he picked it up, he cried out loud, “What can I do?”

It was dark. He could hardly see the road. He looked up and saw a speck of light not far ahead. It was the first house he had seen for a long time. What would the folks say if he knocked at the door and said, “Please let me in.”

They would ask many questions. Questions he didn't want to answer. No, he dared not knock on the door ... but as he came closer he saw the shape of a barn. His heart gave a little leap of hope. He could hide in the barn and sleep there all night. In the morning, he could decide what to do.

He was in luck. The barn door was not locked.

A cow greeted him with a soft moo when he stepped inside. A horse whinnied. It was very dark in the barn, but it smelled of hay and good animal smells. It was warm, and dry, and safe.

He closed the door carefully and felt around until he found a pile of hay. He stripped off his damp jacket and cap, pulled off his wet boots, and burrowed deep into the scratchy, sweet-smelling mow.

He was almost asleep when he heard something rustling in the hay. A wet nose touched his face. Soft fur rubbed against his cheek and a loud purr sounded in his ear.

“Hi, puss,” he whispered, smiling to himself.

The cat snuggled warmly beside him. In a few moments, they were both sound asleep.