Plague (39 page)

“Did she not think to keep him?”

“She did. But growing up with an actress in the Town, opposed to the boy’s own family in the country? And since yond puppy Rochester still refuses to acknowledge the boy …” He frowned. “So it was best for the lad, and perhaps Sarah too. She would not let me escort her when she gave him up, requested to be alone.”

A few paces away, Bettina was making her eyes big at Pitman, gesturing to the stage above. “I am summoned, man. So tell me quick—what is this employment the king has offered you?”

“Groom of the Bedchamber. A sinecure. I don’t think I actually have to lay down in the same room with him.” He laughed. “Od’s life, with Old Rowley ’twixt the sheets, a man wouldn’t get a wink for all the damned

cries d’amour

!”

Pitman didn’t laugh. “A job for life, though—his life, anyway. You would be wise to take it.”

“I would.” Coke ran his fingers over his moustache. “Yet when has wisdom been one of my qualities? I’d be interminably bored. Besides, I have been offered other employment. Less wise. More interesting.”

“I know. I offered it to you. Are you accepting?”

“I think I am.” Coke grinned. “You said it once: thief and thief-taker—what a pair we will make!”

He held out his hand. Pitman clasped it, burying it in his massive ones. “We will, Captain. There’ll be takes aplenty too, for this late plague has thrown many out of work and made them desperate. Thieves abound in London.”

“And not only native ones. Did you hear that dastard Maclean escaped Newgate last Tuesday just before the courts sat again?”

“Aye, and Wednesday robbed Lord Butler on Turnham Green. Maclean’s price has gone up to twenty guineas.”

“Good. Though I’d pay twenty to hear him play ‘Whisky in the Jar’ on his damn fiddle while kicking his heels on Tyburn gallows.”

“Save the king’s money and your own,” Pitman said, releasing the captain’s hand and nodding at the approaching women, “for you’ll be needing it.”

“Eh?” Coke said, but was unable to question further as Bettina swooped in and dragged her husband toward the stairs, beyond which the orchestra was now in full melody.

“I like that Mrs. Chalker,” Bettina said as they climbed. “She may be an actress and so hell-bound for being cousin to a whore, but she’s still one of us.”

“When the time comes, my dear, I hope your liking will extend to helping her with her child. In about six months, I should say.”

“What? Did the captain tell you she’s with child?”

“Nay. Indeed I do not think he knows.”

“Then how do you?”

“ ’Tis my genius for observation, love. And experience.” He stopped them and laid his hand briefly on his wife’s belly. She won’t be able to wear her new dress much longer either, he thought, but said, “Let’s to the play!”

Just as Sarah and William passed the front of the theatre, the second act began. The doors were open to late trade and they could hear Betterton’s rich voice: “ ‘Sblood! She could not have picked out any devil upon the earth so proper to torment her.’ ”

“Are you certain you do not wish to watch the second act?” William asked.

“I will be in the playhouse soon enough again. I would rather enjoy my freedom.” She sniffed the air. “It smells like spring today, does it not?”

“It does.” As they crossed Lincoln’s Inn Fields, he marvelled at the warmth and, even more, the normality. People strolling and enjoying the sunshine; oyster sellers selling oysters, maids their ribbons or combs.

“It is as if the plague never was. Yet I hear some still die of it.”

“I have heard so as well. In the poorer parts of the city. The monster never entirely quits the labyrinth.” He squeezed her hand. “But the king would not have returned nor the gathering places been reopened if there was a general danger still.”

“I am not concerned for my life. Yet I am sad about those who lost theirs.”

“As am I.” They gazed at the ground for a moment, neither with the other, both with Lucy. He was always a little surprised how

readily the tears still came. He looked up, saw a match in her eyes. “Come, love,” he said. “How would you spend this free day of yours? Shall we walk? Or shall we retire to your apartments?”

There was a change in his voice, light now in his eyes. “Truly, was last night not enough for you, sir?”

“You were gone to Cornwall a long while. A month. And you only admitted me to your bed and your heart a short month before that.”

“Two months. How swiftly a man forgets!” She laughed and kissed him. “Why not your apartments?”

“Dickon’s there. The place is a shambles of lurid pamphlets and nut shells.”

“Mine, then,” she said. “But first, William—” she resisted his immediate pull toward Sheere Lane “—let us go and see the puppets.” He knew when he was beaten. “Your servant ever, madam.”

As they crossed the Fields, walked down to Fleet Street and then along the Strand toward Charing Cross, she wondered if tonight would be the night to tell him. It would change what was between them, and she was not sure she wanted that, this time of happiness to end. Yet she knew there could be happiness after too. Coke was not a man like Rochester. He would not disclaim his paternity. Indeed, she felt the captain would attempt to rush her to an altar—and she was not sure how she felt about that. She’d been a widow for ten months. Should she not last at least the year?

She glanced at him. He looked content. There would always be that darkness in his eyes, which she had noticed the very first time she met him. He had seen too much in his life. As had she. Indeed, they made quite the pair. Nay, I’ll leave him in this content for one more night, she thought.

The puppet theatre was as crowded as the playhouse, both newly reopened and drawing their partisans. A silver crown secured them

a place on the front bench, as well as two oranges, two tumblers of ale and two bags of peanuts, one of which Coke pocketed to save for his ward.

The play had already begun, but the plots were never hard to grasp. Nor the characters: a scold, a cuckold and a curmudgeonly master who gossiped, setting the scene. Then on came Punchinello, leading with his vast belly, matched by his hunched back. “Eh! Eh! Eh!” he called, “ ’As anyone seen my wife, eh? Eh?”

The audience roared. The puppet turned to acknowledge them. This slow-moving marionette, with his small dark eyes peering past his huge hooked nose, always disturbed Sarah near as much as he amused. Especially now, when Punchinello appeared to stare right at her. She shivered.

“Here, my love.” William unclasped his cloak, swept it off his shoulders and over hers. He tucked her tight, and she leaned her head against his chest. Must keep her warm, he thought. Especially now. Her and the new life inside her.

The audience laughed and Captain Coke did too. Only he was not laughing at the puppets.

In some ways, I have been researching this book all my life.

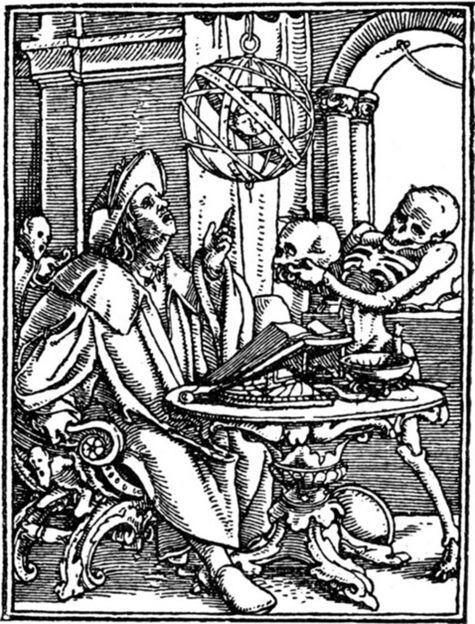

Growing up in London helped. I believe that an event as traumatic as the Great Plague leaves a terrible scar on a city’s psyche, and its inhabitants can’t help but sense the impact somewhere deep within. I remember having plague pits pointed out to me as a child, and staring fascinated at grassed mounds of earth. I was told there was one under St. George and the Dragon at St. John’s Wood Roundabout, near Lord’s Cricket Ground. Certainly the skeletons of victims are still being excavated as the Crossrail project is dug through the city. We walk on plague corpses every day.

As a teenager, madly in love with history, I joined the Sealed Knot—an English Civil Wars reenactment group. I fought in a number of battles (including Lansdown, where Quentin Absolute fell) and rose to the rank of sergeant in the same regiment I have placed Captain Coke, Sir Bevil Grenville’s Regiment of Foote—whose colonel, in a marvellous literary link, was Count Nikolai Tolstoy, grandson of the novelist.

I also admit that I once went to a cockfight. I was travelling around Peru in 1988, staying near the famous Nazca Lines, and felt I should attend in the spirit of research—at least, that was my excuse! It was as brutal as you can imagine. The images lodged in my head, and are now out upon my pages.

Yet nothing could truly prepare me for the other horrors I was to read about and ultimately set down. The period was not one I’d

studied much, except in that basic schoolboy way. The first shock was in reading about the English Civil Wars—the British, really, as they ravaged all the isles. I think I’d retained my Sealed Knot view of something rather chivalrous and romantic. They were nothing of the kind. The images we see each day from various parts of the world remind us that civil war is the most brutal of all. Close to a staggering 10 percent of the population died, many in battle, most of the starvation, sickness and violence that occurred away from the battlefield. I realized quite quickly that most of the former soldiers I turned into characters in this book would have been suffering the seventeenth-century equivalent of post-traumatic stress disorder. It does not excuse but may go a little way to explaining some of their actions.

There were happier areas of research—studying the English theatre, which I love and have been a part of; and studying that formative time when actresses were first allowed to grace the stage. (What would my life have been without actresses?) And the Twitter and email feeds of

The Diary of Samuel Pepys

I signed up for have been a daily joy, as well as vitally informative about customs, food, manners, songs … and pubs! Sam sure liked his bevy, from morning drafts for breakfast to Rhenish in the evening and many ales in between.

I was also fascinated by the turbulent religious times. The wars, fought at least partly about God and how you saw him, unleashed a massive diversity of belief—from the extremely puritanical to its opposite, as exemplified by the Ranters, who worshipped the Almighty by living in communes where they ripped off their clothes, swore, drank, smoked and practised free love. As Lawrence Clarkson, aka Captain of the Rant, wrote: “Devil is God, hell is heaven, sin holiness, damnation salvation: this and only this is the first resurrection.”

Such was the combustible mix at the heart of London. There were so many stunning books I read about the times, and the pestilence in particular, and I list them separately. One, Defoe’s

Journal of the Plague Year

, was wonderfully evocative and expounded superbly in the notes in the Oxford Classics Edition. He coined the fabulous term for the plague: “The Monster in the Labyrinth.” It was, and London was, and it is with fascinated horror that I have wandered my native streets again, literally and on the page.

I hope I have come close to an accurate portrait of time and place. I am sure there are things I’ve got wrong. But before I receive letters, I need to confess something: I have changed a few dates. The Earl of Rochester attempted to abduct the heiress Elizabeth Mallet on May 26, 1665. The theatres were closed for the plague on June 5, 1665. For dramatic purposes, I have amalgamated the two events. I also reopened the theatres somewhat early. Also the earl may have only spent three weeks at his majesty’s displeasure, rather than the three months I have here.

There are so many people I need to thank for the creation of this novel that I have done so in the Acknowledgements. Here, I just need to thank, well, London. Since I no longer live there, I find I cannot stop writing about it. Each time I go back, I learn something new. And each time I also thank providence that I get to write about these extraordinary periods in history and do not have to live through them.

Scarify the buboes, indeed!

C. C. Humphreys

Salt Spring Island, B.C., Canada

July 2014