Planet of the Bugs: Evolution and the Rise of Insects (21 page)

Read Planet of the Bugs: Evolution and the Rise of Insects Online

Authors: Scott Richard Shaw

PLATE 10. A pair of brightly colored tortoise beetles (order Coleoptera, family Chrysomelidae) display just the right combination of body armor, defensive chemicals, and aposematic coloration to leisurely feed on leaves in the Ecuadorian cloud forest. The chrysomelid leaf beetles are a highly successful group of plant feeders in the New World tropics. (Photo by Angela Ochsner.)

PLATE 11. Careful handling this one! The caterpillar of a hemileucine saturniid moth (family Saturniidae) displays its defense mechanism: brittle, hollow spines loaded with irritating toxic chemicals. This approach works well to protect these caterpillars from predation by birds and other vertebrates but does nothing to defend them from parasitism by small wasps and flies. (Photo by Jennifer Donovan-Stump.)

PLATE 12. Large adults of

Automeris abdominals

are frequent visitors to the lights at the Yanayacu Biological Station. By day they rest with their brown forewings covering their hind wings, rendering them very cryptic on leaf litter. When disturbed they reveal the bright hind wings with large eye spots, which may induce a startle response in predatory birds. (Photo by Angela Ochsner.)

7

Triassic Spring

April is the cruelest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

T. S. ELIOT,

The Waste Land

It’s difficult to judge the seasons in Wyoming. In June, sporadic rain transforms the prairie grassland into an endless vista of emerald green, which waves in the wind like a vast ocean. At higher elevations the mountain meadows are awash with red, yellow, and blue wildflowers, which overnight might be buried under a snowfall. By July, the summer drought quickly dries out the grasslands and flowery fields, and the prairies and meadows turn golden brown for another ten months. Even so, in mid-July, it’s not unusual for a hailstorm to cover the ground with ice pellets.

The trees unfortunately don’t help much. Deciduous ones like aspens and poplars don’t leaf out until late May or early June. Autumn comes early. The first killing frost usually occurs in mid-September, and the fierce Wyoming winds quickly strip the trees of dead leaves by early October. The broadleaf trees tend to be without leaves for a full eight months. If you judge the winter by when the trees are bare, then it lasts a long time.

It’s not so easy to judge by snow, either, which at high altitudes can come during any month. Our heaviest storms tend to arrive very early in the fall or late in the spring, burying Wyoming in white crystal flakes in October or May. If that’s not confusing enough, some of the most pleasant weather is liable to show up in midwinter. On most days in January or February, the skies will be totally clear and lumi

nous azure blue. The winds tend to blow away the snow, or it desiccates in the dry air, so long stretches of winter may be totally without any snow cover.

Anyone who has lived in Wyoming can probably understand T. S. Eliot when he wrote that “April is the cruelest month,” as the onset of spring is particularly hard to judge. On sunny days, tulips and daffodils rapidly shoot up, usually to get frozen in ice or buried under snow. There are two other indicators of spring aside from the first flowers, and they’re especially significant because they remind us of the Triassic years, 252 to 201 million years ago. The first is the traditional one: the appearance of robins and other migratory birds. In my home state of Michigan, the robin is indeed a pretty good sign of mild spring weather. Wyoming is crueler: more often than not, this bird appears all puffed up, and desperately tries to keep warm by hiding among the snow-laden spruce boughs during a late spring blizzard. But why would robins remind us of the Triassic?

When I was a child, birds were birds and dinosaurs were thought to be great reptiles. How times have changed. We now understand the message of the wishbone: birds are direct descendants of the dinosaurs, the most famous of all groups which originated during the Mesozoic era.

1

The dinosaurs first evolved during the Triassic years, and the feathered dinosaurs and first birds arose during the Jurassic; while the big dinosaurs like

Tyrannosaurus

and

Triceratops

went extinct at the end of the Cretaceous, the little feathered ones flew on into history. More species are alive now than during Mesozoic times. They just have feathers, wings, beaks, and no teeth. We should remember the dinosaurs every spring when we see the first robin.

But in Wyoming the migratory birds can be unpredictable. In some years they are late arriving, and in others they seem to bypass our area entirely. So I’ve found another indicator of spring, a resident animal that’s a sure sign every year: xyelid sawflies, which live at high elevations near conifer trees and willow bogs. In the early spring, color returns to the willow twigs, providing bright yellow, orange, and red twiggy contrasts against the brilliant white snowbanks melting along the hillsides. Soon the willow buds swell and burst into a profusion of furry pussy willows. Once they start producing pollen, some very tiny insects arrive to gather a high-protein meal. Among them are the xyelid sawflies, which after emerging from their overwintering cells

in the soil are usually the first adult insects to become active in the Wyoming mountains.

Xyelid sawflies are living fossils, relicts of the Triassic years. They are the most primitive living group of the insect order Hymenoptera, the lineage that now includes some of the most successful of all insects: bees, ants, social wasps, and parasitic wasps. And what curious creatures they are. The base of their antenna and maxillary palpus (a segmented feeding appendage located behind the mandible) are leglike, giving them the appearance of having extra legs near their front end. They use their leggy mouthparts to gather a meal, and then they fly up to the tops of nearby conifers, just as they did millions of years ago. The name “sawfly” refers to the females’ serrated egg-laying organ, what entomologists call an ovipositor. With it the females abrade slits into developing pollen-bearing pine cones and insert eggs into the nutritious plant tissue. After the eggs hatch, the young xyelid larvae feed on the tissue, drop to the soil, and finally dig cells in which they pupate until the following spring. This habit served the ancient sawflies well, as it allowed their larvae to live in the treetops, where they were able to evade even the tallest of the dinosaur macroherbivores: the brontosaurs.

2

Breaking the Silence of Permian Extinction: Triassic Not-So-Silent Spring

What period of life could be more springlike than the Triassic? After the catastrophic end-Permian mass extinction came a time of rebirth. The landscape was drier than during the Paleozoic years, but the Triassic forests became dominated by new kinds of plants: mostly conifers, cycads, gingkoes, and ferns. Triassic conifers are now famous because some of them fell into rivers and were washed into coastal lowlands, where they were buried in volcanic debris. Over time these trees fossilized into colorful quartz minerals and became the petrified trees located across the southwestern United States, especially in Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park.

There were no flowering plants, fruit, berries, or grasses in the Triassic. Still, with the prevalence of conifers and the loss of the ancient insect orders, Triassic forests would look familiar to us. Myriad aquatic insects, including mayflies, damselflies, stoneflies, and cad

disflies, fluttered along the streams. The forests buzzed and hummed as legions of new species appeared, especially among the roaches, crickets, planthoppers, true bugs, lacewings, beetles, scorpionflies, and true flies. The Triassic also saw the origin of several new insect groups, some unfamiliar and some now very familiar, such as the walking stick insects, webspinners, earwigs, dobsonflies, snakeflies, and wasps. Vertebrates were busy snapping at all these creatures: the first turtles, salamanders, frogs and of course, most notably, the very first dinosaurs had arrived. By the Late Triassic, several dinosaurs roamed the forests, including some very small bird-sized species like

Saltoposuchus

and

Procompsognathus

, and a few larger ones like

Plateosaurus

.

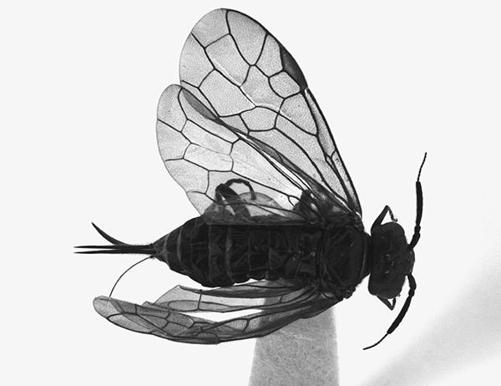

FIGURE 7. 1. A xyelid sawfly,

Pleroneura californica

, a sure sign of spring in Wyoming, is a relict of an ancient insect family that arose during the Triassic period.

You’ve no doubt heard lots about the dinosaurs’ impressive dynasty. They certainly became the dominant macroherbivores and macropredators of the Mesozoic era, fiercely overshadowing the mammals for a hundred million years or more.

3

But I’ll put a twist on the story: dinosaurs were impressive characters in a big Mesozoic world already largely filled with insects. We don’t usually hear much about the both

of them together, but dinosaurs must have influenced the insects, and I’m sure the insects affected the dinosaurs.