Poison

Authors: Jon Wells

Table of Contents

Also by Jon Wells

Heat: A Firefighter’s Story

(James Lorimer & Company)

Sniper

(John Wiley & Sons)

Heat: A Firefighter’s Story

(James Lorimer & Company)

Sniper

(John Wiley & Sons)

Copyright © 2008 by Jon Wells

Care has been taken to trace ownership of copyright material contained in this book. The publisher will gladly receive any information that will enable them to rectify any reference or credit line in subsequent editions.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data

Wells, Jon

Poison : from Steeltown to the Punjab, the true story of a serial killer / JonWells.

eISBN : 978-0-470-73891-7

1. Dhillon, Sukhwinder. 2. Dhillon, Parvesh. 3. Khela, Ranjit. 4. Murder—Ontario—Hamilton. 5. Murder—India—Punjab. 6. Serial murderers—Ontario—Hamilton. 7. Serial murderers—India—Punjab. I. Title.

HV6248.D49W.152’30971352 C2008-902161-4

John Wiley & Sons Canada, Ltd.

6045 Freemont Blvd.

Mississauga, Ontario

L5R 4J3

6045 Freemont Blvd.

Mississauga, Ontario

L5R 4J3

QW

This one is for Scott Petepiece. Even on my best writing

day, I could never string words together that would

adequately express the infinite value of your friendship

over the years, in all of life’s arenas.

day, I could never string words together that would

adequately express the infinite value of your friendship

over the years, in all of life’s arenas.

PREFACE

In the fall of 2001 I was asked to write a series on the crimes of a serial poisoner for

The Hamilton Spectator

. To that point, I had enjoyed the variety of writing at the newspaper. Highlights included covering the U.S. presidential race in Washington, L.A., New York and Miami, Pierre Trudeau’s funeral in Montreal, the crash of United Airlines Flight 93 in rural Pennsylvania on 9/11, and following Tiger Woods over four days at the Canadian Open. When approached with this new task, I wasn’t sure I even wanted to focus on a single story over the long haul. Soon enough I understood the expectations. Editor-in-Chief Dana Robbins told me to craft a series that, long down the road in my career, I’d look back on as “the best thing I ever wrote.” Seven years later, the

Poison

story might just qualify; without question I could never have imagined a more exhilarating creative experience.

The Hamilton Spectator

. To that point, I had enjoyed the variety of writing at the newspaper. Highlights included covering the U.S. presidential race in Washington, L.A., New York and Miami, Pierre Trudeau’s funeral in Montreal, the crash of United Airlines Flight 93 in rural Pennsylvania on 9/11, and following Tiger Woods over four days at the Canadian Open. When approached with this new task, I wasn’t sure I even wanted to focus on a single story over the long haul. Soon enough I understood the expectations. Editor-in-Chief Dana Robbins told me to craft a series that, long down the road in my career, I’d look back on as “the best thing I ever wrote.” Seven years later, the

Poison

story might just qualify; without question I could never have imagined a more exhilarating creative experience.

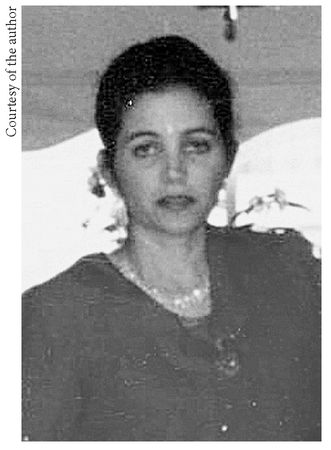

I worked on the piece almost exclusively for over a year. For inspiration, early on I posted a color photo of Parvesh Dhillon, the killer’s first victim, at my desk. Her beautiful face and haunting green-blue eyes looked at me every day. I quickly discovered the story had everything: a greedy and lecherous killer; dashing detectives driven to hunt him down across the globe; dynamic prosecutors and defenders battling through a protracted trial full of twists and turns. The question was, how to do it all justice given the confines of daily newspaper journalism?

I had dreamed of writing a book since I was a teenager, had even penned a couple of spy “novels” in my English journal at A. B. Lucas high school in London, Ontario. With Dana establishing the sky as the limit, from the start I wanted to write it long, taking as my inspiration both mystery fiction and the novelistic journalism of my hero, Tom Wolfe. I told few colleagues of my ambition, and half expected that at some point an editor would see a draft then tell me to scrap it and write a conventional five-part report. Instead, they let me write my book.

All of the detail in

Poison

is true, based entirely on reportage. Research took me through piles of court transcripts and police

investigative documents. I conducted more than 70 interviews —including detectives, lawyers, and the presiding judge—and hired a Punjabi interpreter so I could talk with the families of victims in Canada and India. I also spent two blazing hot weeks in the Punjab with photographer Scott Gardner, where we retraced the steps of the killer and those of Canadian and Indian investigators who chased his shadow there, from chaotic cities to dusty villages. Documenting what we saw, heard, smelled, and felt was a writer’s nirvana.

Poison

is true, based entirely on reportage. Research took me through piles of court transcripts and police

investigative documents. I conducted more than 70 interviews —including detectives, lawyers, and the presiding judge—and hired a Punjabi interpreter so I could talk with the families of victims in Canada and India. I also spent two blazing hot weeks in the Punjab with photographer Scott Gardner, where we retraced the steps of the killer and those of Canadian and Indian investigators who chased his shadow there, from chaotic cities to dusty villages. Documenting what we saw, heard, smelled, and felt was a writer’s nirvana.

In the end the story came out as I had hoped.

Poison

broke new ground in print journalism, running in the

Spec

every day over five weeks. It won a National Newspaper Award (Canada’s Pulitzer’s) and I have now edited, polished, and updated it for this book—the book I set out to write from the start.

Poison

broke new ground in print journalism, running in the

Spec

every day over five weeks. It won a National Newspaper Award (Canada’s Pulitzer’s) and I have now edited, polished, and updated it for this book—the book I set out to write from the start.

As it happened,

Poison

was a beginning for me, not an end. I have written six more book-length narratives, but the original experience remains a part of me that never fades—and neither does the face of Parvesh, who still looks at me across my desk each time my fingers touch the keyboard.

Poison

was a beginning for me, not an end. I have written six more book-length narratives, but the original experience remains a part of me that never fades—and neither does the face of Parvesh, who still looks at me across my desk each time my fingers touch the keyboard.

Jon Wells Hamilton, Ontario

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I want to express gratitude to Don Loney, Executive Editor at John Wiley & Sons, for making this book possible, and to An-drew Borkowski for his assistance editing the manuscript. I thank Dana Robbins for giving me the opportunity to tackle the original

Poison

story for

The Hamilton Spectator

, and both Dana and Roger Gillespie for their encouragement and guidance. Also for their contributions to the original story in the

Spectator

, thanks to Dan Kislenko, Douglas Haggo, and Bob Hutton; Dan for his support and editing of the project, Doug for his impeccable copy editing, and Bob for his design.

Poison

story for

The Hamilton Spectator

, and both Dana and Roger Gillespie for their encouragement and guidance. Also for their contributions to the original story in the

Spectator

, thanks to Dan Kislenko, Douglas Haggo, and Bob Hutton; Dan for his support and editing of the project, Doug for his impeccable copy editing, and Bob for his design.

The research journey to India was the trip of a lifetime, and I was fortunate to experience it with the brilliant photographer Scott Gardner, who is also quite simply a great road trip partner. Kevin Dhinsa, Crown prosecutors Brent Bentham and Tony Leitch, defense lawyer Russell Silverstein, and Justice Stephen Glithero were invaluable sources. I thank Punjabi interpreter Neeta Johar, and, in India, the indispensable Inspector Subhash Kundu, who, among other things, helped us find villages that do not exist on maps. As always I thank Pete Reintjes for his assistance. And I reserve special thanks for Warren Korol, the lead detective on the case with Hamilton Police, for investing his trust in me when his initial instincts surely urged otherwise.

CHAPTER 1

DEATH GRIN

“Kuchila.”

The Punjabi shopkeeper cocked his head, feigning puzzlement. The customer repeated the word, more phonetically this time—“koo-chi-la.” The wide, dark eyes seemed to convey both anger and confusion. In India, those meeting him for the first time noticed a peculiar light in them—the literal English translation of the word describing it would be “too sharp,” but what they meant was the dark side of clever. Wicked.

An aromatic cocktail filled the hot air in claustrophobic Sarafa Bazaar, in a city called Ludhiana, in the northern Indian province of Punjab—samosas frying in oil, warm bananas, roasting corn, incense, the sweet pungency of burning garbage, and the shaving cream lathered on perspiring faces of Hindu men on the sidewalk, ready to be scraped by rust-stained blades. Sikhs in colorful turbans rode scooters through teeming crowds, weaving around rumbling rickshaws that spewed diesel exhaust into the soupy haze, announcing their passage with the dominant sound of India’s cities—the horn. The turban, worn atop bundled hair, is a sacred cloth for Sikh men, a symbol of their violent history of survival. At nearly 10 meters when unwound, it is long enough to cover a Sikh man’s body if he dies in righteous battle.

The customer was a Sikh. But he did not wear the turban. Thick in the chest and shoulders, full stomach straining against the shirt, his size loomed like an insult among the smaller Indian men. Ink-black hair styled longer in the back, beard trimmed, he looked like a foreigner next to orthodox Sikh men who let their hair and beards grow as a sign of humbleness before God.

Raw

kuchila

was available in the market to those who were persistent. The seeds are brown, rough textured and round, the size of a walnut but flat. The trees that bear them grow along the Coromandel coast on India’s southeastern tip. The botanical name is

Strychnos nux-vomica

. In India’s homeopathic lore, a refined version of

kuchila

(the English word is strychnine) taken in precise, highly diluted quantities is said to stimulate the senses, invigorate muscles, even enhance sexual satisfaction. Consumed incorrectly, the result is something entirely different.

kuchila

was available in the market to those who were persistent. The seeds are brown, rough textured and round, the size of a walnut but flat. The trees that bear them grow along the Coromandel coast on India’s southeastern tip. The botanical name is

Strychnos nux-vomica

. In India’s homeopathic lore, a refined version of

kuchila

(the English word is strychnine) taken in precise, highly diluted quantities is said to stimulate the senses, invigorate muscles, even enhance sexual satisfaction. Consumed incorrectly, the result is something entirely different.

On the trip back to Canada, he cleared customs at Pearson International Airport in Toronto. He spoke quickly in a nasal voice pitched higher than his burly physique suggested. He was an excellent liar, the unblinking eyes conveying a guileless innocence. He returned to his home in Hamilton, the steel town on the western tip of Lake Ontario, southwest of Toronto.

Grind the seeds in the mortar and pestle into a white paste. Squeeze the tiny headache medicine capsule, pull apart the fragile casing. Dump some of the existing powder, dip a knife in the paste. Gingerly now, on the knife, into the capsule. It only takes a fraction of what you could fit on your fingernail. Slide the two halves of the capsule back together. Death is God’s will.

Hamilton, Ontario

January 30, 1995

January 30, 1995

Sikh tradition dictated that Parvesh must not cut her hair, ever, and so she tied it back, trapping it. But after a shower, her hair, black as a moonless night, hung free, long and wet. Both girls in school, husband away, for the moment. She basked in the quiet, her migraines and back pain magically absent.

Parvesh Dhillon

Other books

Little House On The Prairie by Wilder, Laura Ingalls

Rest Assured by J.M. Gregson

The Smaller Evil by Stephanie Kuehn

Weekend with Death by Patricia Wentworth

The suns of Scorpio by Alan Burt Akers

JakesPrisoner by Caroline McCall

ALPHA SPEED DATING (BBW) (Rocky Mountain Shifters) by Arden, Susan

Remember by Karthikeyan, Girish

Royal Love by John Simpson

The Book of Daniel by Mat Ridley