Pompeii (22 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

We know the names of thousands of people of Pompeii, from the grand families of the Satrii or the Holconii Rufi to the single names or nicknames of those who scrawled, or were scrawled about, on the walls (who were not necessarily, of course, any less grand – graffiti writing not being a habit restricted to the underclass): ‘Hello my Prima wherever you are. From Secundus. Please love me darling’, ‘Ladicula’s a thief’, ‘Atimetus got me pregnant’. We can even occasionally put faces to names, even if some of the formal statues of local notables that still survive do tend to flatter their subjects beyond credibility. Standing on his plinth in the plaza outside the Stabian Baths on the Via dell’Abbondanza, Marcus Holconius Rufus, city bigwig of the Augustan period, was dressed up to look more like a conquering Roman emperor than a small-town official (Ill. 71). More realistic perhaps – or at least funnier – is the caricature of one ‘Rufus’, complete with his Roman nose (Ill. 41).

What has proved particularly tricky is matching houses to names or families, and this becomes an even trickier process if we try to think in terms of the ‘housefuls’ of people and dependants that might have lived together in a single establishment. As we saw earlier, very many of the identifications are not much more than guesswork, based on groupings of election posters which are taken to indicate either that the candidate concerned, or the canvasser, lived close by – or on signet rings and seal stones. It is not too much of an exaggeration to say that wherever the poor refugees from the city had the misfortune to drop their signet rings on their dash out of town, that is the place where they have been deemed by archaeologists to have lived.

41. ‘This is Rufus’ – ‘

Rufus est

’ as the original Latin reads. The subject (or victim) of this caricature is shown with a laurel wreath, pointy chin and magnificent ‘Roman’ nose.

Occasionally the guesses prove right, or at least half right. It was suggested decades ago that the proprietor of a small bar, standing one block south of the Via dell’Abbondanza, was a man called Amarantus – on the basis of an election notice outside in which one ‘Amarantus Pompeianus’ (that is ‘Amarantus the Pompeian’) urges his fellow townspeople to elect his own particular candidate. At the same time, on the basis of a signet ring, it was decided that the small house next door was owned by Quintus Mestrius Maximus.

These properties have recently been re-excavated. This new work has shown that in the last years of the city the two houses were joined and that they were in a very run-down state. The bar counter was ruined, the garden overgrown (pollen analysis produced some tell-tale bracken spores), and the combined property was being used as a warehouse for wine jars (

amphorae

). The skeleton of the mule which had been used to transport these was found there, along with a (guard) dog by its feet. On two of the wine jars was the name ‘Sextus Pompeius Amarantus’, or just ‘Sextus Pompeius’. The business, such as it was, must indeed have been in the hands of this Amarantus, whose name also crops up in a couple of graffiti found elsewhere in the neighbourhood. Indeed, it may not be too fanciful to imagine that the big-nosed chap (or alternatively the man with the beard) pictured next to a scrawled ‘Hello Amarantus, hello’ is a picture of the man himself (Ill. 42). And Quintus Mestrius Maximus? He might have been his partner, or simply the owner of a lost ring.

42. ‘Hello Amarantus hello’ (or, in the hard to decipher Latin, ‘

Amarantho sal(utem) sal(utem)

’). Presumably one of these men is meant to be the Amarantus who owned the bar where the graffito was found.

The truth is that we can very occasionally be certain about the identity of the occupants of a house. One example would be the house of Lucius Caecilius Jucundus, whose banking records were found fallen from the attic. A little more often we can be reasonably confident about who they were. Despite the odd nagging doubt, the balance of probability must be that the House of the Vettii was the property of one, or both, of the brothers Aulus Vettius Conviva and Aulus Vettius Restitutus (though one sceptical archaeologist has recently come up with the idea that they were a couple of dependants, charged with stamping goods in and out of the house). The House of Julius Polybius takes its modern name from a man who appears as both candidate and canvasser on election notices on its façade and inside the house itself. But it is also strongly connected with a Caius Julius Philippus, probably a relation, whose signet ring was found inside one of the house’s cupboards – and not therefore casually dropped – and who is also mentioned in writing inside the house.

But when we know the identity of the occupants, what extra does that tell us? With Amarantus, it gives us nothing more than the satisfaction of being able to put a name to a house. But in other cases, further information we have about the people concerned, or even just the name itself, can point in interesting directions. The fact that one of the Vettii brothers was a member of the local

Augustales

(part social club, part priesthood, part political office, see pp. 212–13) is a powerful hint that they were themselves ex-slaves, since the

Augustales

were almost entirely made up of that rank of Roman society. In the case of Julius Philippus and Julius Polybius, whatever the precise relationship between them, their name alone suggests that – however lofty their status in the political elite of Pompeii by the middle of the first century CE – they too may trace their descent to freed slaves; for the name Julius often indicates a slave freed by one of the early emperors whose family name was Julius. These are all nice indications of the permeable boundary between slave and free in Roman society.

79 CE: all change

It is almost inevitable that we know most about the houses in Pompeii and about their occupants as they were in the last years before the eruption. But we can still see something of the redesigns, extensions and change of function that marked their history. Like any town, Pompeii was always on the move. House owners grabbed more space by buying parts of the neighbouring property and knocking a door through. The boundaries of the House of the Menander expanded and contracted, as its owners either bought up or sold off again parts of the next-door houses. The House of the Vettii was formed by joining together, and adapting, two smaller properties. Shops opened up and closed down. What had been residential units were converted to all kinds of other uses: bars, fulleries and workshops. Or vice versa.

There is an obvious temptation to blame any apparent shift downmarket on the effects of the earthquake of 62 CE. In fact, where there is no other evidence, it has always been convenient to date industrial conversions to ‘post-62’. But beware. It is clear that these kinds of change had a much longer history in the town than that. One careful study of three fulleries which are usually assumed to have ‘taken over’ private houses after the earthquake has shown that all three of them co-existed with the residential function of the houses (despite the dreadful smell). At least one of the conversions was definitely to be dated before 62.

Yet, there

was

an enormous amount of construction work and decorating going on at the time the eruption came, more than seems easily compatible with the usual processes of change and renovation. And there is some evidence, beyond that, for decommissioning and downgrading. To take examples only from houses we have met so far: in the House of the Prince of Naples, what had been a grand entertainment room appears to have been in use for storage; so too in the House of Julius Polybius (where some of the rooms were also empty, and jars of lime were found, suggesting ongoing restoration); in the House of Venus in a Bikini, redecoration had been started and shelved; it was still going on, it seems in the House of Fabius Rufus and the House of the Vestals; in the House of the Menander, the private bath suite was largely out of commission, having collapsed or been dismantled; in the little House of Amarantus building materials were also found, but there was no sign of active work (plans may have been abandoned).

It seems implausible that all this activity had been caused either by the general need for running repairs, or by the earthquake as long ago as 62 (in fact some of the work was clearly repatching the repairs already carried out ‘post-62’). Almost certainly, much of what we see is the response to the damage caused by pre-eruption tremors, over the weeks or months before the final eruption itself. It was not business as usual for householders in Pompeii in the summer of 79 CE. For the optimists among them, it must have been a series of annoying cracks in the paintwork which needed fixing. For the pessimists (and those with the leisure to worry about their future), it must have been a time to reflect on quite what was going to happen next.

It is to the reaction of one family of optimists, living in the House of the Painters at Work, that we turn next.

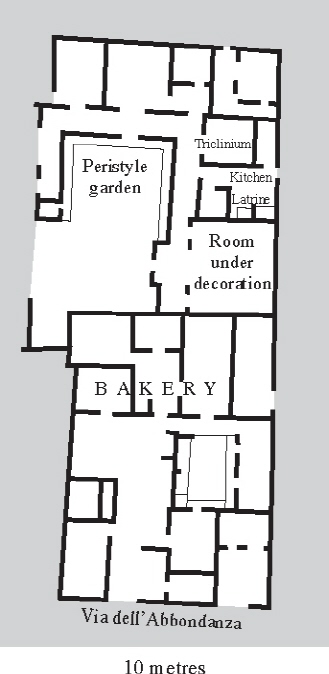

Beware: painters at work

On the morning of 24 August 79 CE a team of painters, perhaps three or four altogether, had turned up at a large house almost next door to the House of Julius Polybius to continue a job they had started a couple of weeks earlier. Exactly how large, or grand, this house was we do not yet know, for it has not been completely uncovered. What we have so far is only the rear portion of the property: a peristyle garden (described on p.87), the rooms around it, and a small entrance onto a side alley (Fig. 10). Between the back wall of the garden and the Via dell’Abbondanza there stood – in one of those characteristic Pompeian juxtapositions between upmarket residence and the economic infrastructure – a shop and a commercial bakery (which we shall visit in the next chapter). The main front door of this house, now known for obvious reasons as the House of the Painters at Work, must have opened onto a street to the north.

Major redecoration works were obviously going on. Piles of lime were found in the colonnades of the peristyle, as well as sand and mosaic

tesserae

and other flooring material in a dump near the kitchen. The painters were in the middle of their work in the most impressive room of this part of the house, some 50 square metres, opening onto the garden. They must have taken to their heels sometime around midday, leaving their equipment and paints behind almost in mid-brushstroke. Compasses, traces of scaffolding, jars of plaster, mixing bowls have all been found there, as well as more than fifty little pots of paint (including some – mostly empty ones – stacked in a wicker basket in one of the rooms to the north of the peristyle, which was obviously being used as a store during the building works).

Figure 10

. The House of the Painters at Work. This house has still not been fully excavated. Its rear portions abut onto the Bakery of the Chaste Lovers. The front entrance must be somewhere to the north (above).

Thanks to the sudden interruption we get a rare glimpse of their handiwork before it was quite complete, and from that we can begin to reconstruct how they worked, in what order, how quickly and how many of them there were. One basic principle is – and it is not much more than common sense – that they started at the top and worked down. Although the uppermost levels of the room are now almost completely destroyed, it is clear that the very top sections of the wall had been finished and painted. So too, to judge from fragments found fallen to the floor, had the coffered ceiling. The very bottom level of the wall, below the ‘dado’, had not been given its final coat of plaster.