Postcards (32 page)

Authors: Annie Proulx

In the moment of falling he wanted to chop her throat, split the humped black hair to the brain. He came up from the floor like a hammer. He thought he would have killed her except for Criddle and Ben Rainwater, finally, coming in, felt hat tilted over his eyes. The three men staggered around in a surging dance. Mrs. Criddle shoved Marta out through the kitchen and into the alley.

‘I don’t care if you don’t got your coat, you go on home if you got one.’

And through the rage Loyal tasted an evil satisfaction that adrenaline had stalled his fit. Although no secret was unfolded. And wrote that night at the top of the page in the Indian’s book,

Only one way,

then scored the words out until the pen tore the paper, shut those thoughts down. Who knew how many ways there were to love? Those who could not find any way knew the difficulties.

JEWELL WOKE UP with the feeling she had to make haste. There were things to be done, set aright. She drank her cup of tea standing up, looking out at the dark morning. Her hands rattled the cup. Unsteady on her pins, too, she thought, but felt restless. Must be a weather change coming in.

She washed the cup and saucer and ate a few slices of apple. No appetite these days. Stout since Dub was born, her flesh had fallen away in the past year. Her reflection startled her – old Grandma Sevins, beaky nose and wrinkles, peering at her. She was seventy-two and looked it, but felt like a young woman except for the shakes.

It was too bad, she thought. She’d missed the leaves turning color

again. It had been at its height in October when the new car’s brakes were being replaced, and then the whole idea had slipped her mind while Indian summer skidded past. She’d always intended to go up in the mountains over in New Hampshire at leaf time when she got done at the cannery. They said it was a treat, the colors and the views. She longed to drive up Mount Washington, up the toll road. And then, when she had time on her hands, she’d forgotten about it. She thought the Beetle would make it; they said the road was hard on cars and not a few had to turn back. The ones that boded over. But at the summit you could see to the end of the world, could buy a sticker for your car bumper that said

THIS CAR CLIMBED MT. WASHINGTON

. Silly thing to want, a bumper sticker, but she did want it. Mount Washington. Now there was something for an old girl to do!

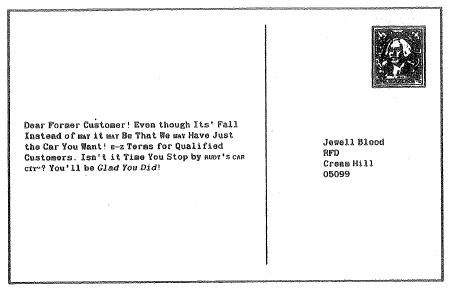

Ray had persuaded her to trade in Mink’s ancient pre-War heap for a 1966 VW Beetle. ‘It’s only got twenty-two thousand miles on it. It’ll last as long as the old Ford did, it’ll get good mileage and you can take it places most cars won’t go. Rudy’s got one in pretty good shape. The color’s kind of funny but he says you can have it at a good price.’

‘I don’t care about the color!’ she said. Then, ‘What color is it?’

‘It’s orange, Jewell. With lime-green upholstery. It was a custom order but the people couldn’t keep up the payments. It runs very good and it’s got a good heater. No body rot at all. Rudy says he’ll replace the brakes for free if you’re interested in the car. I think he’s having trouble selling it because of the color and that’s a fact.’

She liked the little car once she got past the way it looked. The vehicle’s humped shape and eagerness seemed familiar; it reminded her of Mernelle’s old dog.

She straightened up the trailer, ran the vacuum cleaner over the braided rug, spread a clean tablecloth and put fresh shelf paper in the kitchen cupboards. That was a little job. In the old days she would have stuffed the dirty paper in the stove and burned it. The electric stove was clean but it couldn’t dry socks, burn paper, raise bread or provide comfort. Cost money to run it. They called it progress.

By nine there was nothing to do but knit. She was restless. The

wool caught on her rough fingers. The trailer cramped in. She felt like a good drive, wanted to get out on the road and see something. The trailer was cozy enough, but it cramped her up. The truth was, she missed working at the cannery.

She studied the dull morning. The sky was like an old horse blanket. The gaunt weeks before the snow started. Well, she would just drive east even though it looked like rain. See how far she got. Let the Beetle do what it could.

She was in Littleton at noon, tired and thirsty. She spent fifteen minutes looking for a luncheonette. She had the beginning of a headache. It was a longer trip than it looked on the map. The heavy sky loured. A glass of ginger ale would do good. Maybe a chicken sandwich while she studied her map. It was still a treat to go into a place and order what she liked, then pay for it with her own money.

She parked in front of The Cowbell Diner. Inside she sat in a varnished booth, pulled out the menu stuck behind the napkin dispenser. Crumbs and ketchup smears on the table. One waitress leaned on the counter; the other sat on a stool in front of her, smoking and drinking coffee. There were a few other customers. A man in a ragged jacket seemed at home; he helped himself to coffee from the murky pot behind the counter.

‘Takin’ their sweet time,’ Jewell muttered to herself.

The girl came over and swiped a rag over the table.

‘Help you.’

‘I believe I’ll have a glass of ginger ale without any ice and a plain chicken sandwich, just chicken and lettuce and a little mayonnaise.’

‘White or whole?’

‘What?’

‘You want the chicken on white bread or whole wheat bread?’ She jiggled her thigh, looked back at the other waitress. Jewell recognized the type. There was a kind of salesclerk, waiter, waitress, cashier, barely civil to older people. They took their time, spoke contemptuously, slapped down the goods. Jewell bet this one would slop the ginger ale all over the place. Sure enough.

The bread curled up like a pagoda to disclose wilted lettuce and a wad of grey chicken. The ginger ale was mostly ice and slosh. She

mopped up the spilled liquid with paper napkins and bent over her road map. Dismayed to see the auto road was on the far side of the mountain. She would have to drive north and all the way around, another sixty miles, it looked like. When the waitress brought her check – $1.75 – she asked her if there was a faster way to get to the auto road.

‘Auto road? I don’t even know where it is. Melanie, you know where the auto road is?’

‘For Mount Washington,’ said Jewell. ‘The auto road that goes up Mount Washington.’

‘I been up it,’ said Melanie. ‘It was cloudy.’

‘What’s the best route?’

‘Just take one-sixteen, then get on two, then get on sixteen, that’s all I know. A couple hours from here, anyway.’

‘Aren’t there any shortcuts, any back roads?’

The first waitress answered. ‘Not that I ever heard of. So, where’d you go last night, Melanie?’

The man in the plaid jacket swiveled around on his stool. ‘You got a good car?’ Unshaven jowls, eyes like pickled onions. Old coot.

‘Yes, I do,’ said Jewell, thinking of the earnest Beetle. ‘I drive it anywhere.’

‘Well, you got a good car and don’t mind gettin’ off the main road, they’s a shortcut, save you eight or ten mild.’ He hitched across the door and hovered over the map. It’s a loggin’ road. Forget one-sixteen. See, you go down here, see, take one-fifteen, go down past Carrol, about three mild past Carrol, then you start watchin’ on the right. Row of equipment sheds, I dunno, six, eight sheds, and after the sheds there’s a right-hand turn. You don’t take that one, but about half a mild farther there’s another right-hand turn and that’s the one you want. It cuts along over here, comes out somewhere there.’ His finger skidded across the map. ‘Save you some mild, ’bout ten mild. If you don’t mind a dirt road.’

‘That’s mostly what I drive on,’ she said. ‘Appreciate the information.’

‘I wouldn’t take his advice if you paid me,’ said Melanie.

It was quarter of two when she came to the rickety pole sheds. She passed a right-hand turn, and watched the odometer to know when she reached half a mile. Nothing. At one and six-tenths miles a ragged gravel road cut southeast. She turned onto it. Not a breath of wind. The dark sky, the chewed spruce of the idiot strip and behind it rough hills choked with brambles and popple trash depressed her. She was tired. Cold seeped into the Beetle. Probably be close to four and starting to get dark when she reached the top of Mount Washington. What time did they close the shop where you got the bumper stickers? But she was so close it would be a shame not to try. An adventure, going up Mount Washington in the near dark. And coming down again. Don’t let it rain, she thought, glad she had the new brakes.

The road roughened, narrowed, pale gravel through the dark woods. A mile or two in, the road formed a Y. There were no signs, no way to tell which went where. The right branch seemed the best bet and she turned onto it. The nameless road crossed a bridge, then twisted uphill in loops and curls; innumerable side roads branched to the left, the right. Mile after mile the road bored into the forest. She passed log landings, an ancient green trailer with a caved-in roof and a pair of antlers dangling over the gaping doorway. The road went black and mucky in the low spots. Mud sprayed up onto the windshield. The gravel had played out. She fought up a grade of shelf rock and onto a corduroy trail of rotting logs through a swamp. There was no place to turn around. She was frightened now and wanted to turn back, but could only go forward. The first ticks of freezing rain. A moose splashed into a stand of spruce stubs. The little car wallowed through holes and the muffler tore loose on one of the logs before she was out of the swamp. The track – it was no longer a road – steepened, a gullied-out nightmare of stones. She could not turn around, could barely go forward.

The fine sleet built up on the windshield. The wipers rasped ineffectually at the mud and ice. Finally, a lurch to the side, a grinding. The Volkswagen was hung up. She switched off the ignition, got out and looked underneath, saw the rock pressing against the undercarriage. The sleet rattled on the little car, hissed in the spruce. It would take a helicopter to get the Beetle off that rock, she thought. There had

been a come-along in the old car’s trunk, but it had disappeared when she got the Volkswagen. But if she could find a stout pole or two and get them under the Beetle maybe there was a chance to lever it off. If she had the strength. She was bound to try. But wished for Mink. Saw how he used his rage to pull him through difficult work, through a difficult life. Her heart was pounding. She stumbled into the slash, looking for a good, sound stub. She wasn’t dressed good for this, she thought, the knit pants cuff catching on snags.

Branch slash, decaying trunks, green saplings – nothing that would do. It was the hardest kind of work getting through the tangle of deadwood. Panting, she came to a gully crisscrossed with dead trees, boding with brambles. There was a stub that looked sound and of a size she could manage. She tried for a good position to haul at it. She could lift the near end free, but the far end seemed to be moored by another trunk. She was shaking. Would have to get to the other side of the gully and pry it loose somehow. Knew she could not balance her way over on the fallen trunks like a tightrope walker, like Mink would have done. She struggled, clawed down into the gully, began to force her way through choked brambles and rot. The sleet pattered. It was dark and stinking down in the close stems. Branch stubs jabbed. She fought her way forward, seven, eight feet, her heart hammering, so intent on reaching the other side of the gully she felt only astonishment when the fatal aneurism halted her journey. Her hand clenched wild raspberry canes, relaxed.

DRUMMING NOVEMBER RAIN streamed over the windshield. Gusts rocked the car, slapped wet leaves into the street. Ray’s milky breath condensed on the side windows softening the glare of stoplights, the neon sign

CHIN GARDEN

(the

a

in China had never worked) into colored lozenges. The heater whirred its warmth onto his legs. He turned onto Henry Street, the headlights throwing off sparkles from wet trees, the flecked sidewalk. Water charged with leaves raced in the gutters, wet boots flashed like flints. The windows of his house shone in the darkness like squares of melting butter.