Power Up Your Brain (11 page)

Read Power Up Your Brain Online

Authors: David Perlmutter M. D.,Alberto Villoldo Ph.d.

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #General, #ebook, #book

Because these emotions are associated with the Four F’s—fear, feeding, fighting, and fornicating—they are primitive and instinctual, originating from a prehistoric neurocomputer that we share in common with all mammals. If you experienced physical or verbal abuse in your childhood, you are at risk of associating intimacy with danger in the family you create with your spouse. One terrifying experience during a walk in a big city after nightfall can cause you to link large urban communities with peril. In this way, you rekindle the embers of old memories and bring them into the moment, where they burn with great intensity.

Instinctual emotions linger. If you are angry and it passes after a few minutes, this is a cognitive emotion. If you are angry for 20 days or 20 years, this is an instinctual emotion. Instinctual emotions become like toxic programs that take over our entire neurocomputer. These neural networks cause us to waste precious years in an angry marriage or fettered to an unfulfilling and frustrating job. Eventually, when we think we have finally had enough, we might quit the job or storm out of the marriage, not realizing that what we need to change is our neural networks through which we engage in our current environment and situations.

REINFORCING TOXIC NEURAL PATHWAYS

AND SUBCONSCIOUS BELIEFS

Neural networks are a plastic, dynamic architecture, a constellation of neurons that light up momentarily to perform a specific task. This is why, as you mull over a particular thought (good or bad) or practice a particular activity (beneficial or detrimental), you reinforce the neural networks that correlate with those thoughts and skills. Each time a situation reminds you of an actual fearful or dangerous experience from your past and instinctual emotions are brought up, that specific neural network is reinforced. We strengthen the toxic emotions and neural networks in our limbic brain and begin to create subconscious beliefs about life. These beliefs drive our actions and reactions in all experiences.

PTSD, Emotional Stress, and Suffering

When we are exposed to severe trauma, we can develop a condition known as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Studies show that most people are likely to experience at least one life-threatening or violent event in their lifetime.

1

The studies indicate that even if a person recovers from PTSD, he or she may continue to show mild symptoms.

2

With PTSD many of life’s typical events are inappropriately routed through the limbic brain, where we relive, at least from an emotional perspective, the heart-wrenching trauma of events that may have occurred decades ago. PTSD is compounded because the limbic brain, primal as it is, can’t tell time and therefore can’t distinguish the difference between a painful event that occurred 20 years ago and the memory of that event triggered by a similar situation today.

3

As an example, it was common for soldiers who returned from the Gulf War and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to become anxious or distressed when they heard fireworks or other sudden loud noises because their limbic brain did not understand it was no longer in the theater of war. Similarly, couples who go through a bitter divorce may recoil in shock when they hear each other’s voice many years after the marriage has ended.

But you do not have to be diagnosed with PTSD to have even seemingly benign events trigger intense emotional reactions.

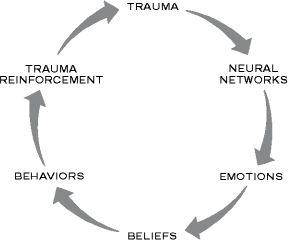

This reinforcement can be done without our knowledge or when we are milking an emotional

trauma

for sympathy, whether from others or from ourselves. We might say, for example, “I don’t have to act maturely; after all, I had a terrible childhood.” By creating and repeating such a statement, we reinforce

neural networks

and emotional habits that are as distinct as the postural habits from an old whiplash injury that has affected the vertebra and muscles of the spine. These networks give rise to

emotions,

then

beliefs

that keep us favoring past pain, as well as

behaviors

that continually

reinforce the trauma

as well as the pity we have learned to so successfully milk.

Diagrammed, the pattern looks like this:

While such a repetitive, circular pattern once served to ensure our survival, it has become toxic and has given rise to erroneous beliefs about the world and acquaintances, friends, and even family. Because beliefs can be unconscious, they may present themselves in ways that surprise us. We may start an intimate relationship that falls apart when we discover the person is not really who we thought he or she was, but the situation might actually be the product of our own unconscious belief that we will never find a partner. Likewise, we may have a terrific career opportunity that collapses because deep down we believe that we are not worthy.

Oddly enough, you can actually reinforce the toxic networks established by traumas by reacting with fear to a

perceived

threat. Unfortunately, whenever a situation is even faintly similar to some painful event from your past, a red flag goes up in your mammalian brain and you perceive it as a possible threat. This is because trauma is not what actually happened but how you stored it as a story in your mind. That is to say, you are impacted by what you

believe

occurred. And this story is kept alive below the threshold of consciousness, without your thinking or being aware.

Alberto:

Soul Retrieval

One of my patients was haunted by a recurring image of herself as a six-year-old child when she was hit by an automobile while riding her bicycle. Although “Carol” was unhurt, she remembers lying underneath the stopped vehicle, seeing the underside of the engine, and smelling the overpowering odor of oil and grease. When she recalled this incident, she remembered calling for her mother and father, neither of whom responded. The only one to help her was the stranger who had been driving the automobile.

Years later, Carol continued to be haunted by this feeling of abandonment. She felt that her mother and father had never really been there for her when she needed them and that she could only rely on strangers, who were the very same people who would hurt her. Working with that perception, the neural networks in her limbic brain created erroneous beliefs about friendships and support systems that led her to inappropriate relationships and behaviors.

Carol completely trusted people she met in airplanes and at parties, yet she distrusted her family and friends who genuinely tried to advise and help her. She felt tremendous anger toward her parents but would forgive strangers for the most heinous acts.

Carol only began to heal when I helped her revisit that event during a guided meditation. We coaxed that part of her personality that had “split off” or disassociated during the accident to come back. In doing so, we had to reassure Little Carol that Big Carol would look after her and protect her and welcome her with gifts and beauty. Shamans refer to this process as

soul retrieval,

and, in effect, I did help Carol recover lost qualities of her soul: trust, curiosity, security, confidence, and spontaneity. As she embraced these qualities, she opened the way for new neural pathways that would allow her to experience the world more creatively. She began to perceive people and situations in a new way, seeing opportunities where before she had only seen adversity.

ENDING THE PROPENSITY FOR SUFFERING

For many years, psychology embraced the idea that destructive emotions could be repaired with therapy, a view that is questioned today by some practitioners, who are even debating the legitimacy of psychology itself. The psychoanalyst James Hillman, for example, writes, “The failure of psychotherapy to make clear its legitimacy has resulted in psychologies which are bastard sciences and degenerate philosophies. Psychotherapy has attempted to support its pedigree by appropriating logics unsuited for investigating its area. As these borrowed methods fail one by one, psychotherapy seems more and more dubious—neither good physics, good philosophy, nor good religion.”

4

In our respective professions, we (the authors) have come to know many dedicated psychotherapists who are working in schools, prisons, and neighborhood health centers. These practitioners are fiercely committed to helping their patients alleviate their suffering and fit better into society. Yet, we agree that popular psychological platitudes and pop spirituality have served little purpose beyond miring us further in our painful stories.

While the media have popularized issues regarding inadequate parents, abandonment, and low self-esteem, commentators and critics have fallen far short of providing satisfying explanations that will console our complex personalities. At best, media attention and open dialogue have helped many of us understand how the painful events and trauma we experienced in childhood have shaped our relationships. Yet, this understanding has done little to rewire the neural networks in our brain that keep us trapped in these stories, which is the only thing that could really help us feel better about ourselves or free us to lead more fulfilling lives.

Instead, we go around explaining to ourselves and others why we’re incapable of loving or trusting, or why we are reluctant to believe in our self-worth. We claim it is because our mothers didn’t nurture us or our fathers mistreated us. In other words, we continue to subscribe to debilitating narratives—many of them of our own creation—about who we are and what we are capable of accomplishing. And we keep buying self-help titles that perennially top the best-seller lists!

So, why don’t we get better? Because we are looking for answers in all the wrong places.