Pox (38 page)

Authors: Michael Willrich

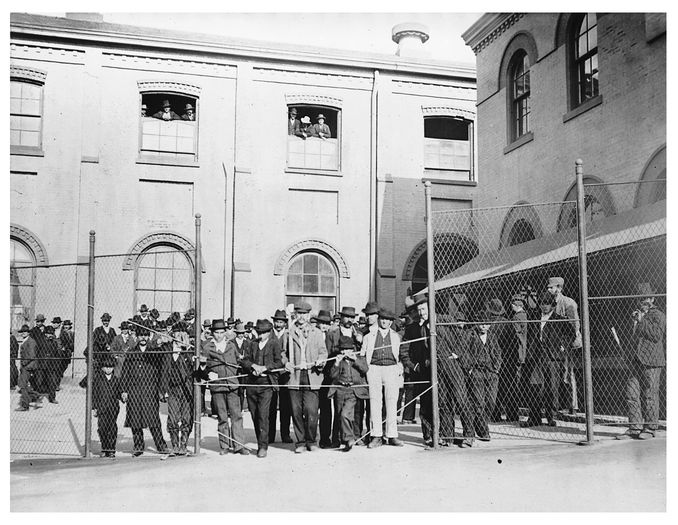

Immigrants from a smallpox-infected ship, detained in 1901 at the quarantine station on Hoffman Island, N.Y. Photo by Elizabeth Allen Austen.

COURTESY OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

COURTESY OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Â

Along the borders with Canada and Mexico, U.S. quarantine law called for aliens to enter only through designated points. Such rules proved difficult to enforce, particularly along the Rio Grande. Many Mexicans, accustomed to traveling freely across the border for work or to visit relatives, viewed the tightening system of inspection around the turn of the century as a violation of their rights. In a single week in February 1899, Acting Assistant Surgeon H. J. Hamilton and his staff at Laredo, Texas, inspected more than 2,500 migrants crossing the Rio Grande via the Laredo Foot Bridge, a truss bridge built in the 1880s, or by ferry or train. Most of the people he met at the footbridge insisted upon their “right to pass” without inspection. But that was a privilege the Service extended only to affluent travelers. While the Service routinely inspected all arriving passenger trains from Mexico, checking all second- and third-class passengers for “recent vaccine scars,” inspectors allowed travelers in the Pullman cars simply to swear to their immunity. In his time at the post, Hamilton concluded that the poorer class of Mexicans reckoned smallpox a fact of life and feared vaccination far more than the disease.

35

35

In the winter of 1899, Surgeon General Wyman received a flurry of dispatches from Laredo, a border city of 15,000 people, the majority of them of Mexican descent. Virulent smallpox had raged there for months, with 376 cases and 83 deaths reported in January and February. (The death rate indicates an epidemic of classic variola major.) Hamilton advised the local authorities “to issue some law compelling vaccination, by force if necessary.” In March, Texas health officer W. T. Blunt arrived from Austin. City officials set about fumigating homes, vaccinating, and removing infected residents by force to the pesthouse. The actions targeted the poorer barrios on the east side of town. Meeting strong resistance from the residents, Blunt called in the Texas Rangers. In the ensuing violence, one Mexican American leader was killed, thirteen people were wounded, and twenty-one were arrested. A contingent of the U.S. Tenth Cavalry arrived, and Hamilton took charge of the local vaccination corps. Even with so many soldiers in the area, fifteen residents “had to be reported, arrested, and then vaccinated.”

36

36

Even beyond the nation's borders, the mark of vaccination became a powerful signifier of American rule. In September 1905, more than 650 black contract laborers from Martinique traveled aboard the French steamship

Versailles

to Colón, a port city located near the Atlantic entrance to the U.S.-controlled Panama Canal Zone. As the crowded ship approached the port, laborers in canoes paddled up to the ship, warning the passengers that poor treatment and harsh conditions awaited them on shore. The messengers said that vaccination, required of all immigrant laborers by the American sanitary regulations of the Isthmian Canal Commission, would produce “an inextinguishable mark” that would make it impossible for them ever to leave the Isthmus. The migrants refused to leave the ship. The next morning, officials persuaded 500 of them to land. But 150 men remained on board and demanded to be returned to Martinique. A force of Panamanian and Canal Zone police forced the migrants from the ship. According to

The Washington Post

, “nearly everyone of them had been clubbed, and several were bleeding from nasty wounds.” Many had jumped overboard. Later that same afternoon, all of the laborers were vaccinated, loaded on a train, and shipped out to Corozal, where they were put to work building the canal.

37

Versailles

to Colón, a port city located near the Atlantic entrance to the U.S.-controlled Panama Canal Zone. As the crowded ship approached the port, laborers in canoes paddled up to the ship, warning the passengers that poor treatment and harsh conditions awaited them on shore. The messengers said that vaccination, required of all immigrant laborers by the American sanitary regulations of the Isthmian Canal Commission, would produce “an inextinguishable mark” that would make it impossible for them ever to leave the Isthmus. The migrants refused to leave the ship. The next morning, officials persuaded 500 of them to land. But 150 men remained on board and demanded to be returned to Martinique. A force of Panamanian and Canal Zone police forced the migrants from the ship. According to

The Washington Post

, “nearly everyone of them had been clubbed, and several were bleeding from nasty wounds.” Many had jumped overboard. Later that same afternoon, all of the laborers were vaccinated, loaded on a train, and shipped out to Corozal, where they were put to work building the canal.

37

In the hands of a subordinate people, a rumor can be a surprisingly potent political toolâa “weapon of the weak”âeven when the rumor is not true. But the canoe riders of Colón did not exaggerate. In the Canal Zone, only the immigrant workers were compelled to be vaccinated. The doctors uniformly scraped their right arms. Foremen and canal officials used the marksâmuch as the slave catchers of the remembered past had used brandsâto identify and apprehend runaway workers in the Panamanian jungle.

38

38

Â

Â

W

atching with dismay as smallpox spread across the American heartland in 1901, Dr. James Hyde of Chicago's Rush Medical School urged state and local governments to use their full police powers to eradicate this affront to modern civilization. Like many of his professional peers, Hyde found the metaphor of the vaccine scar as passport irresistible. He urged that American governments require this medical mark for entry into the country's civic spaces. “Vaccination should be the seal on the passport of entrance to the public schools, to the voters' booth, to the box of the juryman, and to every position of duty, privilege, profit or honor in the gift of either the State or the Nation,” he declared. In one respect, vaccination seemed superior to a printed identity document; this government-certified ticket of immunity was stamped indelibly upon the body. Seasoned health officials did not trust the paper vaccination certificates issued by private physicians; they always asked to see the scar. As one writer noted in

American Medicine

, “This certain, well-defined sign cannot be forged.”

39

atching with dismay as smallpox spread across the American heartland in 1901, Dr. James Hyde of Chicago's Rush Medical School urged state and local governments to use their full police powers to eradicate this affront to modern civilization. Like many of his professional peers, Hyde found the metaphor of the vaccine scar as passport irresistible. He urged that American governments require this medical mark for entry into the country's civic spaces. “Vaccination should be the seal on the passport of entrance to the public schools, to the voters' booth, to the box of the juryman, and to every position of duty, privilege, profit or honor in the gift of either the State or the Nation,” he declared. In one respect, vaccination seemed superior to a printed identity document; this government-certified ticket of immunity was stamped indelibly upon the body. Seasoned health officials did not trust the paper vaccination certificates issued by private physicians; they always asked to see the scar. As one writer noted in

American Medicine

, “This certain, well-defined sign cannot be forged.”

39

That writer was wrong. As health officials and police tightened enforcement of vaccination at public schools, industrial work sites, and railroad depots, Americans started forging scars. Some tried plaster fakes. Others followed recipes printed in unorthodox medical journals and passed along by word of mouth. “Get a little strong nitric acid,” advised the Columbus, Ohioâbased journal

Medical Talk for the Home

. “Take a match or a toothpick, dip it into the acid, so that a drop of the acid clings to the end of the match. Carefully transfer the drop to the spot on the arm where you wish the sore to appear. Let the drop stand a few minutes on the flesh. Watch it closely.” After a few minutes, the skin, stinging, turned red. That meant it was time to blot up the remaining acid. In a week, the nickel-sized spot turned dark. “This sore will gradually heal by producing a scar so nearly resembling vaccination that the average physician cannot tell the difference.” Health officials condemned the “vile crime” as the handiwork of a few antivaccination fanatics. But these intimate acts of civil disobedience were part of something larger, a groundswell of popular opposition to “state medicine.”

40

Medical Talk for the Home

. “Take a match or a toothpick, dip it into the acid, so that a drop of the acid clings to the end of the match. Carefully transfer the drop to the spot on the arm where you wish the sore to appear. Let the drop stand a few minutes on the flesh. Watch it closely.” After a few minutes, the skin, stinging, turned red. That meant it was time to blot up the remaining acid. In a week, the nickel-sized spot turned dark. “This sore will gradually heal by producing a scar so nearly resembling vaccination that the average physician cannot tell the difference.” Health officials condemned the “vile crime” as the handiwork of a few antivaccination fanatics. But these intimate acts of civil disobedience were part of something larger, a groundswell of popular opposition to “state medicine.”

40

“True compulsory vaccination,” as Health Officer Charles V. Chapin of Providence defined it, aimed to secure general immunity from smallpox by requiring every member of the community to be vaccinated and periodically revaccinated. The model was Germany, which boasted the world's most vaccinated population and the one most free from smallpox. German law required that every child be vaccinated in the first year of life, again during school, and yet again (for the men) upon entering military service. The U.S. Constitution, as interpreted at the time, foreclosed any serious talk of achieving such a universal system through federal law. That left the matter to the states. Hard political realitiesâthe diversity of state legal cultures, the uneven development of their public health systems, and the suspicion with which many Americans greeted any government interference with their personal libertiesâassured that a German-style system of vaccination, covering the entire U.S. population, never came to pass. Most vaccination laws on the books were the residue of bygone epidemics. As the emergencies that begot those laws faded from memory, enforcement waned.

41

41

For all of these reasons, the epidemics of 1898â1903 found many communities poorly protected by vaccination. New circumstances made health officials' jobs even harder. The advent of a milder type of smallpox and heightened concerns about vaccine safety hindered the efforts of public health officials, who often received little support from lawmakers, government executives, and the public.

Still, when confronted with a costly smallpox epidemic, the same governments that during times of relative health shied away from compulsory measures readily resorted to coercion. The emergency powers they exercised were extraordinaryâparticularly in thickly populated spaces. In his definitive 1904 treatise

The Police Power

, Professor Ernst Freund of the University of Chicago Law School covered every form of state regulatory action from liquor licensing to the suppression of labor strikes to trust-busting. But he singled out compulsory vaccination to illustrate the outer limits of legitimate state action. “Measures directly affecting the person in his bodily liberty or integrity,” he wrote, “represent the most incisive exercise of the police power.” During the turn-of-the-century epidemics, millions of ordinary Americans could not enter their work sites, send their children to public school, or travel freely without showing their vaccination scars. To them, the metaphor of the passport seemed real enough.

42

The Police Power

, Professor Ernst Freund of the University of Chicago Law School covered every form of state regulatory action from liquor licensing to the suppression of labor strikes to trust-busting. But he singled out compulsory vaccination to illustrate the outer limits of legitimate state action. “Measures directly affecting the person in his bodily liberty or integrity,” he wrote, “represent the most incisive exercise of the police power.” During the turn-of-the-century epidemics, millions of ordinary Americans could not enter their work sites, send their children to public school, or travel freely without showing their vaccination scars. To them, the metaphor of the passport seemed real enough.

42

Besides soldiers, prisoners, and immigrants fresh off the boat, the most vaccinated members of American society were public schoolchildren. School vaccination rules paved the way for a growing array of measures governing the bodies and behavior of children, as more and more states made school attendance mandatory into the teenage years. By 1902, nearly 16 million Americansâ72 percent of all children aged five to eighteenâattended public schools; another 1.2 million went to private schools. The great exception was the South, where most state legislatures had yet to compel school attendance or vaccination. In 1901, only five states had laws on the books requiring universal childhood vaccination in the first year or two of life. But most took measures to keep unvaccinated children from the public schools, especially when smallpox threatened. (Some states, including California and Massachusetts, mandated school vaccination by statute; others, such as New Jersey and Maine, authorized school boards to order vaccination; and in still other states, school boards simply issued orders at their discretion.) Almost everywhere, the requirements applied exclusively to public schools. Parents with the means to send their children to private schools could opt out.

43

43

In an era when American governments took ever greater responsibility for childrenâthrough child labor laws, school laws, and new child-welfare institutions such as the juvenile courtâthe vaccination rules served multiple purposes. As some health officers pointed out, it would have been unconscionable for states to require children to spend half their day in crowded classrooms without protecting them against socially transmitted diseases. The measures, coupled with increasingly routine medical inspections in the public schools, also extended state authority from the school into the home, bringing working-class and immigrant parents into line with new progressive norms of hygiene. When unvaccinated children were excluded from school, their parents could face prosecution under education laws. Some officials even imagined that the requirement made a positive impression on the studentsâ“familiarizing the juvenile mind with respect for authority,” as one put it, “whatever the merits of the medical expedient may be.”

44

44

Compulsory vaccination turned American public schools into theaters of conflict. Parents, pupils, teachers, and sometimes even principals challenged the rules with tactics ranging from civil suits to civil disobedience. Parents decried the measures as a violation of their domestic authority and a threat to their children's health. Officials in Chicago and New York uncovered what the

Times

called “an extensive traffic” in phony vaccination certificates. The school strikes that rocked Camden and Rochester after Camden's tetanus outbreak were not isolated incidents. In Gas City, Indiana, two hundred mothers, holding their unvaccinated children by the hand, marched upon the public schools building on a December morning in 1902. Facing down a contingent of policemen at the schoolhouse doors, they demanded that their “scarless” children be admitted.

45

Times

called “an extensive traffic” in phony vaccination certificates. The school strikes that rocked Camden and Rochester after Camden's tetanus outbreak were not isolated incidents. In Gas City, Indiana, two hundred mothers, holding their unvaccinated children by the hand, marched upon the public schools building on a December morning in 1902. Facing down a contingent of policemen at the schoolhouse doors, they demanded that their “scarless” children be admitted.

45

In nearby Bluffton, Indiana, the school board squared off against the health board, refusing to enforce the latter's vaccination order. In Delaware County, Pennsylvania, a group of female teachers refused to let physicians examine their arms for scars, protesting a policy that compelled them to undergo a risky medical procedure before entering their workplaces. Students caused trouble, too. Visiting Newburg, Ohio, Cleveland health officer Martin Friedrich came upon some children outside their school. The students called out to each other, “Are you vaccinated? Are you vaccinated?” Friedrich understood: the vaccinators were in the schoolhouse. He slowed his pace and listened. “Pretty soon I knew what they were up to,” he recalled. The corner grocery-man had told some of them that they should wash the vaccine from their arms to keep them from getting sore. “They communicated it to each other in a most lively manner, and all hurried as fast as they could to the grocery-store to wash their arms.”

46

46

Other books

Playing Hard to Master by Sparrow Beckett

Deathwing by Neil & Pringle Jones

Death as a Last Resort by Gwendolyn Southin

Bad Boy's Heart: A Firemen in Love Series Novella by Starling,Amy

Immortal Darkness (Phantom Diaries #3) by Gow, Kailin

Below Unforgiven by Stedronsky, Kimberly

The Dying Light by Henry Porter

Eat Your Heart Out by Katie Boland

East of Innocence by David Thorne

Ever Wrath by Alexia Purdy