Praxis (34 page)

A letter was passed to Praxis. It came from a film company with which Phillip was involved. It asked her to sign enclosed release forms, so that footage of Praxis in earlier days could be used in a documentary ‘The Right To Choose’, which Phillip was making for the Women’s Movement. Praxis signed, as requested. Motivation no longer seemed of much consequence. Results were what mattered.

‘If the child’s mother says she asked you to do it,’ said the lawyer, ‘we’ll stand some kind of chance.’

‘She didn’t,’ said Praxis. ‘I don’t want her to say it.’

‘I don’t think she will,’ said the lawyer. ‘She’s very bitter.’

Praxis cried at that, and the lawyer looked relieved, as if at last—something he understood had happened.

The day before the trial opened the governor sent for Praxis and handed her a file of letters.

‘We thought you ought to see these,’ she said. She reminded Praxis of Hilda, but perhaps that was merely the capacity she had for writing adverse reports, and circulating them. ‘They might cheer you up. They’re letters of support, from women saying they wish they’d had the courage to do what you did. Mothers mostly, mind you: but grandmothers, relatives, friends as well, who have watched the disintegration of households, as the years pass.’

‘I don’t want to read them,’ said Praxis. ‘I want a rest from other peoples’ misery. Thank you very much, all the same.’

‘Ah well,’ said the governor, disappointed. ‘I suppose we can’t be saints all the time.’

As it was a murder charge, Praxis was handcuffed to a wardress on the way to the court. Through the side window she caught glimpses of groups of women with banners, and the sound of cheers, shouts, and boos. As she stepped from the car she was dazzled by flashlights.

‘People get hysterical,’ she remarked to the wardress, more in the spirit of apology than anything else.

‘Better than being cold-blooded,’ said the wardress, who had a backward brother, could see the convenience of his elimination, despised herself for it, and felt the more antagonism towards Praxis because of it.

‘I’m not,’ said Praxis. ‘I’m not.’ But by whose standards did she judge?

‘Yes,’ said Mary, loud and clear across the court. ‘I asked her to do it for me. She was my friend.’ But she did not meet Praxis’ eye. She would tell a lie on her account, but not forgive her.

‘No,’ said Praxis. ‘Of course I was not the proper person to do it. But who else was there?’

‘No,’ said Praxis, ‘I did not have the right, but the mother did. I was her agent.’

Thus far she would lie to get herself out of trouble.

‘No,’ said Praxis, ‘I see nothing worse in killing a four-day-old imperfect baby than in killing a four-month-old perfect foetus. Except that it’s more disagreeable to do.’

‘No,’ said Praxis. ‘I am not mad, am not receiving psychiatric treatment.’

‘Yes,’ said Praxis, ‘it is perfectly possible that my life to date is indicative of a damaged personality: but most of us are emotionally damaged in some degree or another. We do the best we can with what we have.’

The judge was not unsympathetic. The abortion laws, he said, had confused both the moral and the legal issues.

The father of Ancient Rome (he had a classical education) exercised the right of life and death over a new-born baby. If the living would suffer as a result of its birth—by reason of famine, war, or danger—it was not allowed to live. Nor was a defective child: nor a female, in a family already overcrowded with girls. The decision was taken by the father: the deed performed by a servant. That was in the great days of the Empire.

The jury was out for two days and brought back a verdict of guilty, the judge finally consenting to accept a majority verdict.

Praxis was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment.

Women crowded round the Black Maria as she left the court, tapping at the windows.

‘We’ll be waiting.’

‘Don’t give up.’

‘Don’t give in.’

If there were others—as there surely were—wishing to spit and abuse, or weep and reproach, they did not get near.

Mary went to Toronto, with the children.

Irma came to visit and brought Praxis news of the outside world. Serena had left Phillip. Claire married her business executive: it had been a big wedding and Diana had played the mother of the bride very well, in a blue hat with feathers, as surely she was entitled to do. Mary’s job was going well: she was to specialise in pediatrics. Irma herself was looking ill: she had cancer: she would not have treatment for it. Jason had given in, given up park-keeping and gone back to University. The winter weather drove him to it, he said, and not his father. Though now Serena had left, and Phillip was plainly wretched, he felt more kindly inclined towards him. Robert had decided to stay on in Africa.

‘To shoot Africans, I suppose,’ said Praxis, sadly.

‘You should never have left them,’ said Irma. ‘As you sow, Praxis, so you reap.’

Her own younger son lived with her country cousins. He rode horses and despised city life. Irma did not feel she had to keep alive on his account.

‘As you sow,’ repeated Praxis, ‘so you reap.’

It was, in the end, a comforting doctrine.

‘Do call me Pattie,’ she said. ‘I’ve given up Praxis. It’s a very pretentious name,’

‘Funny,’ said Irma, ‘your sister has started calling herself Hypatia.’

When Pattie Fletcher left prison there was no one to meet her. She had, she assumed, been forgotten by a fickle world. She had very little money and nowhere to live. Irma was in hospital, in a coma. Bess, Tracey and Raya had started a commune in Wales. Pattie could not, without effort, trace their address. She developed a cold, which turned into bronchitis. The Discharged Prisoners’ Aid Association found her a basement room in a familiar neighbourhood: the Social Security people paid her a small weekly sum.

She fell, getting from the bath, cracked her elbow on the floor, tried to go to hospital, had her toe stamped on by the kind of young woman she had helped create, and came home.

She wrote, she raged, grieved and laughed, she thought she nearly died; then, presently, she began to feel better.

T

ODAY I MANAGED TO GET

a slipper on to my foot and a coat on to my back. I left my basement, boarded the bus, was helped to my seat by the conductor and, when I reached my destination, out of it by a handsome young African with curly hair who did not seem in the least averse to taking my uninjured arm.

I arrived at the hospital at half past two and waited for attention in the Out Patients Department until three fifty-five. A handful of patients, who arrived after me but were dripping blood or gasping for air, were seen out of turn, but it was not, all the same, as long a wait as I had expected. Who wants to look at an old woman’s toes when the lives of the young and virile are at stake, and the red blood spurting free? But I was not actively discriminated against. And the tea, offered by kindly volunteers, was of good quality and served in unchipped mugs and with unlimited sugar. (The young despise sugar, these days, seeing it as the root of many evils, both physical and moral, which leaves plenty for the likes of me.)

When I was shown into the treatment cubicle by the nurse, the young woman doctor had her back to me and was studying my notes, as is their custom. I eased my foot from its slipper; my elbow from my coat. I was dizzy with mingled pain and relief. The doctor turned. She had a pretty, alert face. She wore no make-up. She reminded me of Mary: She seemed puzzled, as Mary seldom was. Mary’s fault, if she had one, was a surfeit of certainty.

‘Pattie Fletcher?’ she enquired, staring at my card, then at me. ‘But I know your face from somewhere.’

I wished she would concentrate on my injuries.

‘You’re Praxis Duveen,’ she said, ‘that’s who you are.’

I had the impression that she fell on her knees, but it can hardly have been so. At any rate there were tears in her eyes.

‘We didn’t know where you were,’ she said. ‘We thought you must be dead.’

‘Who’s we?’

‘Everyone,’ she said. ‘Oh, everyone. Anyone who saw the film.’

Phillip’s film; his apology: his justification.

‘But what have they done to you?’ she demanded, all ready to be angry.

‘Nothing,’ I said, ‘I did it all to myself.’

She said I was not fit to go home and had me wheeled along corridors and up lifts into a small room off a men’s ward, and the last I saw of her that day was pink-faced and gesticulating to the ward sister, who seemed aggrieved.

I do not want special treatment but I see that I shall get it. I am not suffering from senility, it seems, but malnutrition. They feed me with spoonfuls of scrambled egg, which I hate. My skin is already better, my eyes are brighter, my hair is almost thick. I am not nearly so old as I had assumed. I remember Lucy’s old trick of pretending extreme old age, as if madness were not enough, and she needed that protection too. My manuscript is carefully sorted and safely between plastic folders. There are flowers everywhere.

I do not want any of this: it is not what I meant. The pain in my soul, my heart, my mind, is not assuaged, as are my bodily aches and pains, by recognition and attention. I am surrounded, at too frequent intervals, by a babel of people, mostly women, either embarrassingly servile, or self-consciously unimpressed. Cameras click and whir. I have been elected heroine. In the meantime I worry in case they are neglecting my toe. If it is broken, why don’t they put it in plaster? All they have done is lay it, rather carelessly, in a bed of sticky tape, and. say that will do.

Dear God, do I have to go on living?

It occurs to me that when I address the deity in these terms, it is in the conviction that he exists: or if not a deity, some kind of force which turns the wheels of action and reaction, and gives meaning and purpose to our lives: if not in our own eyes, at least in those of other people.

And there, you see, I’ve done it. I have thrown away my life, and gained it. The wall which surrounded me is quite broken down. I can touch, feel, see my fellow human beings.

That is quite enough.

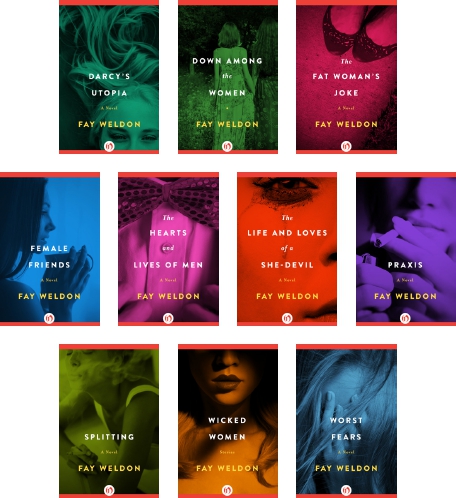

Novelist, playwright, and screenwriter Fay Weldon was born in England, brought up in New Zealand, and returned to the United Kingdom when she was fifteen. She studied economics and psychology at the University of St Andrews in Scotland. She worked briefly for the Foreign Office in London, then as a journalist, and then as an advertising copywriter. She later gave up her career in advertising, and began to write fulltime. Her first novel,

The Fat Woman’s Joke

, was published in 1967. She was chair of the judges for the Booker Prize for fiction in 1983, and received an honorary doctorate from the University of St Andrews in 1990. In 2001, she was named a Commander of the British Empire.

Weldon’s work includes more than twenty novels, five collections of short stories, several children’s books, nonfiction books, magazine articles, and a number of plays written for television, radio, and the stage, including the pilot episode for the television series

Upstairs Downstairs. She-Devil

, the film adaption of her 1983 novel

The Life and Loves of a She-Devil

, starred Meryl Streep in a Golden Globe–winning role.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 1978 by Fay Weldon

Cover design by Connie Gabbert

978-1-4804-1249-1

This edition published in 2013 by Open Road Integrated Media

345 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10014

FROM OPEN ROAD MEDIA