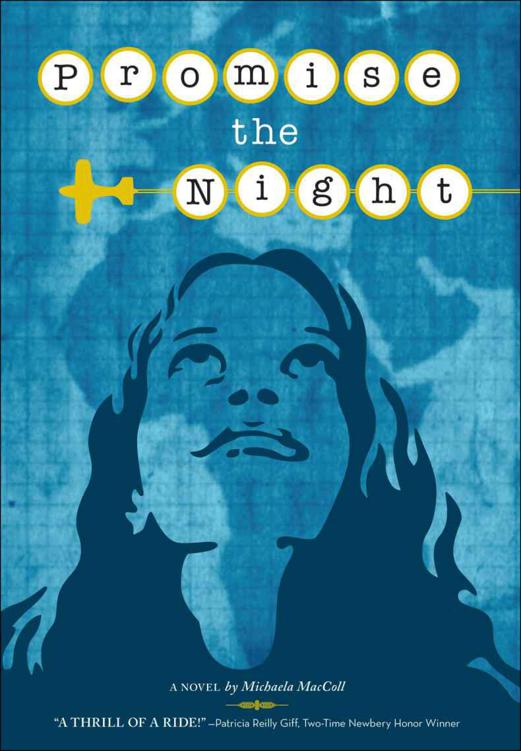

Promise the Night

Authors: Michaela MacColl

To Mom, a fearless pilot and terrific lady. You inspired this book.

The Daily Express

19 August, 1936

London, England

I am going to set out to fly the Atlantic to New York. Not as a society girl. Not as a woman even. But as a pilot with two thousand flying hours, mostly in uncharted Africa, to my credit. The only thing that really counts is whether one can fly. I have a license. I can take an engine apart and put it back. I can navigate. I am fit and given ordinary luck I am sure I can fly to New York.

This is to be no stunt flight. No woman’s superiority-over-man affair. I don’t want to be superior to men. If I can be a good pilot, I’ll be the happiest creature alive.

1912, Green Hills Farm, Njoro, British East Africa (present-day Kenya)

BERYL SAT BOLT UPRIGHT, HER HEART BEATING FASTER. ALONE in her mud hut at night, she expected to hear certain noises: the rustling of insects burrowing in the thatch roof, the snorting of the horses, and sometimes even the roar of a lion in the valley. But these ordinary noises had suddenly stopped.

“Buller, did you hear something?” she whispered. The only answer in the darkness was her dog’s snore from the polished mud floor of her hut. “Some watchdog you are!”

Holding her breath, she listened carefully. Beryl ran her hand under her monkey-skin bedspread, searching for her trusty “bushman’s friend.” Taken secretly from her father’s hut, the vicious blade was sharp enough to deal with anything.

Brushing the mosquito netting aside, she swung her legs off the bed and crept to the door. The only thing between her and the night was a thick burlap sack secured to the door frame with leather ties. She tugged the ties open, drew back the rough cloth, and

slipped outside. With a heavy sigh, Buller lumbered to his feet and joined her.

The cold clear air drove away her drowsiness. Dressed only in one of her father’s old nightshirts, she shivered as the chill sliced through the fine linen. The moon was just rising, illuminating the vast valley dropping away at her feet.

Beryl turned toward the pitch-black forest behind her. She stared long enough for the trees to take individual shape. Her father had forbidden her to go into the forest alone. Any danger would come from there.

Buller lifted his head and sniffed. He whined deep in his throat.

“What do you smell, boy?” Beryl asked. She tried sniffing, too, but inhaling the cold air burned her nostrils. She glanced over at her father’s rondavel twenty yards away. Like her hut, it was covered with a thick straw roof. Until the big house was finished, her father’s house was as tiny as hers. Most settlers slept in their own huts; the mud buildings were quick to build and lasted for years.

A thin line of light illuminated the sacking of her father’s window. He would be doing the accounts. By day, he drove himself and his men to exhaustion. At night, he tried to make the Green Hills farm profitable by writing numbers in different columns. He would be furious if she interrupted his work to report an unusual silence.

Beryl took one last hard look around. She didn’t see anything, but her father always said that what you don’t notice in Africa can get you killed. Glancing into the clear sky, she saw Orion, the hunter, outlined in the stars. He was an old friend. Her view was blocked by an owl, wings extended, who glided above her head with a soft hoot before disappearing into the valley. What must it be like to

soar over the trees and meadows—to see Africa from up high? To be afraid of nothing? To be able to see danger in the dark, not just have vague worries about strange silences?

She slipped back into the safety of her hut, ducking under the burlap door. Buller lay down in his usual spot at the end of the bed. The day after her mother had abandoned Beryl and her father, Beryl had persuaded Buller to sleep with her in the tiny hut. He was as unlike Mama as it was possible to be. She was aristocratic and beautiful. Buller was an ugly mutt, a mix of bull terrier and sheep-dog. But while Mama had left Africa without a backward glance, Buller was still her loyal friend who never left Beryl’s side.

Daddy said Mama left because the size of Africa frightened her. And she wanted indoor plumbing. Beryl could no longer remember her mother’s face, but the sting of her mother not asking Beryl to go with her still smarted. Nevertheless, she managed just fine: alone with her father, Buller, the horses, and Africa, with the nearest neighbor miles away.

Beryl threw herself into bed, tucking the mosquito netting around her body. Holding her knife tightly, she stared into the darkness, listening hard and pinching herself to keep awake.

Later, when it was all over, she wondered what would have happened if she had remembered to tie down the burlap door. If she had not been so careless, would the danger have passed her by?

Her only warning was a patch of lighter night by the door. The leopard must have slunk in, crawling soundlessly on his stomach the way cats do. Ears flat to his head. Spotted fur standing up on his back. Eyes fixed on his prey. Waiting. Waiting…

Buller’s anguished yelp filled the hut. When she heard the deep yowl, she knew it was a cat, probably a leopard. Beryl huddled

beneath the safety of the mosquito netting, afraid the cat would finish off Buller and then go after her.

“Buller! Be careful, boy!” Beryl screamed at the top of her voice. She waved the knife in the dark. She couldn’t see what was happening, but she could hear Buller’s low growl. She imagined that the leopard was poised to spring onto her bed.

“Daddy!” she cried. She ripped off the blanket and snapped it toward the battling animals. Even if she had the courage, Beryl knew she shouldn’t join the fight on the floor; she was just as likely to hurt Buller as help him.

Beryl could make out the leopard’s shadow, spotted even in the dimness. It sprang onto Buller’s back and sank its sharp teeth in the loose skin at the back of his neck.

“DADDY!”

Beryl heard what sounded like Buller’s back cracking as he tried to shake off the cat. Before she could scream again, the leopard had dragged her friend out of her rondavel. Buller’s cries ended as suddenly as they began.

She leapt out of bed and ran into the bulk of her father; he was in the doorway, carrying a hurricane lamp.

“Beryl! Are you hurt?” He ran his hands lightly over her head and body, as if checking the soundness of one of his thoroughbreds. “What happened?”

“A leopard got into the hut.”

“What? Where?”

“It’s gone—he took Buller!” A sob escaped her. “Daddy, Buller’s hurt. We have to go get him.”

“Be quiet, Beryl. Crying won’t help him now.” He stood up and cast the lantern’s light around the room. “Let me look.”

He knelt to the floor and touched a spot. He brought his finger to his nose. “Blood. Whether Buller’s or the cat’s, I don’t know.” He glanced around. “How did he get in? Didn’t you close the door?”

She closed her eyes and sobbed. “It’s all my fault, Daddy!”

“Beryl…stop caterwauling. Answer me. What happened?” The lamp cast a ghostly light on the sharp planes of his face. His gray eyes were unyielding.

“I got up in the night, Daddy,” she admitted. “I forgot to tie the door down.”

“How many times have I told you?” He shrugged. “Careless.”

“I’m sorry, Daddy.”

“It’s a hard way to learn your lesson.” He shook his head, and the lines of his face softened just a bit.

“Daddy, we have to find Buller and save him.” Tears streamed from her eyes. “Please help me, Daddy.”

Her father stared at the pool of blood on the floor of her hut. He didn’t answer.

“Please, Daddy. Please.” Clutching her knife in one hand, she grabbed her father’s hand and squeezed hard with the other.

“Where did you get that knife?” he asked.

“I don’t remember,” she said, not meeting his eyes. “Come on, Daddy. We have to save Buller.”

He shook his head.”Beryl, it’s too late. Either the dog will survive or it won’t.”

Beryl didn’t say a word, but her whole body trembled with pleading.

“Don’t look like that,” he said with irritation. “A farmer’s daughter can’t afford to be sentimental about animals.”

“Please…” Her words came out in a croak. “Buller was Mama’s dog.”

“Oh, for pity’s sake,” he burst out. He pulled his hand away and wiped his brow. “Get your boots on and we’ll take a look around. But it’s probably a wasted effort.”

Biting her lip to keep from crying, Beryl pulled on her boots. She followed her father into the compound as he tracked the spots of blood into the forest by the light of his lantern. There was so much of it—on the leaves of bushes, in pools on the ground. Wherever they followed the blood trace, the forest was silent, as though all the animals and night insects were holding their breath. The nest of ancient trees and vines was even more ominous at night.

After a few hundred yards, they lost the trail.

“Beryl, there’s nothing we can do.”

“I’m sure he’s around here somewhere,” Beryl insisted. “I think I hear him.”

Holding the lantern above their heads, her father placed a hand on her shoulder. “Even if Buller fought back, he’s badly wounded. False hope is worse than no hope at all, Beryl. Especially in Africa.”

“But…”

“No buts. If I have time tomorrow, we’ll look again, but Buller’s almost certainly dead. I’ll get you a new dog.”

“But…”

“Not another word, young lady. And you’ll sleep in my hut the rest of the night. I don’t trust you to be sensible.” He turned and began the trek back to their small compound of huts. Dashing the tears from her cheeks, Beryl cast a last look into the undergrowth.

“Don’t die, Buller. I’ll come for you,” she promised into the darkness.

| LONDON, ENGLAND | 3 SEPTEMBER, 1936 |

We hope Mrs. Beryl Markham will never take off. The time for these “pioneer” solo flights in overloaded radio-less machines has passed…If she came down in the ocean she would cause prolonged suspense to all her friends and considerable inconvenience and expense to all the ships who would have to search for her. We hope that Mrs. Markham will think better of it.

EYES SQUEEZED SHUT, BERYL LISTENED TO THE NOISES OF HER father getting ready for the morning. She lay perfectly still until she heard his voice outside, berating the workers in his British-accented Swahili. As she swung her legs off the extra cot in his hut, a furry, bony hand grabbed her ankle. She stifled a scream.