Psychology and Other Stories (14 page)

Read Psychology and Other Stories Online

Authors: C. P. Boyko

for they tend to produce tension and annoyance inwardly. For example, when you are with a group of people at luncheon, do not comment that the âCommunists will soon take over the country.' In the first place, Communists are not going to take over the country, and by so asserting

you create a depressing reaction in the minds of others. It undoubtedly affects digestion adversely.

It would only have been necessary to replace “Communists” with “rampant militarization” or “the attenuation of civil rights” or “the exploding gulf between rich and poor” to update this advice to the era and milieu in which Jim Bird read these words. There were times, surely, when a little dyspepsia was justified?

Then there was the emphasis put on “help.” A cure always implied a disease. The incredible proliferation of self-help manuals over the past fifty years sent at least one clear message:

You need help.

“Ask yourself whether you are happy, and you cease to be so”; with so many books and magazines and television shows shrilly asking you, again and again, “Are

you

happy? Are you happy

enough

?” was it any wonder that people began to doubt that they

were

happy, or happy enough? With so many medicines being offered, how could one feel healthy? The solutions being offered were themselves the problem. No one ever acquired happiness by grasping at it.

Bird catalogued his criticisms methodically, as though it were his job. For indeed, the idea for a new project had begun to take form. He would write a book, scholarly and caustic, condemning the self-help industry. He needed a new project. It was five years since his first book had been published. An analysis of Nietzsche's conception of the will, the book was more successful than it should have been, for it had appeared at a propitious time. Nietzsche had been prophetic in many areas, but his belief that volition was an illusion, merely the subjective experience of a system of semi-independent urges blindly colliding like chemicals in a beakerâthis view of the mind seemed tailor-made for the so-called “Decade of the Brain,” when neuroscientists and psychologists alike strove to map all the parts of the personality onto sections of grey matter, hoping thereby to prove that we

are nothing but our brains and therefore as much in thrall to the rigid laws of cause and effect as any other physical system. One of the lions of this movement, a famous philosopher who wrote popular books on materialistic determinism (as it was called), even provided Bird's book with a lengthy introduction, in which he generously (if somewhat anachronistically) indicated the ways in which Nietzsche's views echoed his, the philosopher's, own: “The will, as Nietzsche would be the first to admit, is, like consciousness itself, an illusion. What we call âwill' is just the shorthand employed by a complex machine to signify what I have elsewhere called âself-referential subroutines' ⦔ etc., etc. Bird's own name was not mentioned in this introduction, nor indeed were the ideas he presented in the text; Bird was not sure the famous philosopher had even read his book. Nevertheless, for this service, the philosopher's name appeared on the cover in a font that Bird (with a ruler) determined to be only two point sizes smaller than his own. But the book sold well, and Bird's academic future was assured.

The Decade of the Brain, however, had come and gone, and whether or not it had achieved its objectives, Bird knew that he wanted nothing more to do with anything that might appeal to neuroscientists, psychologists, or famous philosophers. He wanted to do something different. Here, at last, in self-help, he had found something different.

But he was afraid that to write this attack on self-help as a philosopher, to write this book as a piece of scholarly and caustic social criticism, would be to write over the heads of the very masses who consumed the stuff. An academic treatise would be “academic” in the worst sense of the word: detached, theoretical, dryâ“merely academic.” You could not denounce the populace from an ivory tower; you had to descend to the streets, like Zarathustra. Bird wanted, more than anything, to address his attack to self-help's adherents. He wanted to write something that his wife might read.

The only way to do that was to speak in their idiom, to adopt the language of the self-help books themselves.

He would write a self-help book to end all self-help booksâan anti-self-help book. He would write a satire.

The writing came easily. Almost too easilyâfor, as Nietzsche said, “The sum of the inner movements which a man

finds easy

, and as a consequence performs gracefully and with pleasure, one calls his soul.” Till now, Bird had taken it as axiomatic that writing was like giving birth: there had to be labor pains. In the past he had never been able to produce more than four or five hundred words a day, for he could not commit a single sentence to paper without becoming paralyzed by the thought that this one idea could be written a million different ways. Nietzsche said that the great writer could be recognized by how skillfully he avoided the words that every mediocre writer would have hit upon to express the same thing. Bird, who wanted only to be understood, would struggle desperately to hit upon those mediocre words; but everything he produced looked awkward, unnatural, flamboyantly recherché. Now, for the first time, the words suggested themselves. He turned out a thousand, fifteen hundred, two thousand words a day. He felt himself almost physically taken over by the projectâmuch the same way (or so he imagined) that Nietzsche had been taken over by the writing of

Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

It was as if this was what, and how, he had been meant to write all his life; and this thought, so damaging to his scholar's ego, was the only dark spot on the otherwise ecstatic joy of composition.

He found that he could mimic the self-help books' conventions almost effortlessly, and indeed with pleasure, for in this medium that he had no respect for he could let himself go completely. Like a patient playing a villain in a psychodrama, he was free to say and do

things he would never have said or done in his own person. It was downright cathartic.

He easily mastered the loose (i.e., ungrammatical), chatty (i.e., slangy), chummy (i.e., badgering) prose style, and had a knack for turning out phrases that could have been self-help boilerplate: “If you don't give in to your true self, your true self will give in to you.” “Smiling is not a panaceaâbut it is a good cure for a frown.” He managed to sustain the requisite tone of manic enthusiasm for over 300 pages through an unending barrage of italics, underscoring, boldface, capital letters, funny fonts, and other typographical tricks for signaling emphasis. He disguised his extended sermon as an interactive dialogue by putting a lot of obtuse questions into his reader's mouth (“I know, I know, you're thinking: But does this really apply to me?”) and then answering them (“You bet it does, buster! It applies to

everyone

”). He borrowed the authority of great thinkers of the past, quoting everyone from Milton to Emerson (especially Emerson). He capitalized dubious concepts and gave them Unnecessary But Impressive Abbreviations (e.g., UBIAs). He manufactured supportive anecdotes and testimonials as needed. He employed a sort of pietistic scientism, citing “recent scientific studies” to demonstrate anything he wanted to demonstrate. He adopted at times a plodding conscientiousness, making clear what was already clear, defining terms in no need of defining, providing several synonyms for commonplace words, as if combating not just the reader's skepticism but their unfamiliarity with the English language. He was shamelessly repetitive, writing the same sentence several times in a single chapter, often verbatim. He summarized chapters in forewords and again in afterwords. He filled entire pages with synoptic tables and lists. (Self-help authors loved lists, especially lists with seven or ten items.) He created an outrageously transparent self-quiz which claimed to help the reader measure their “striving index,” that is, the degree to which they overexerted themselves. (Question number 47:

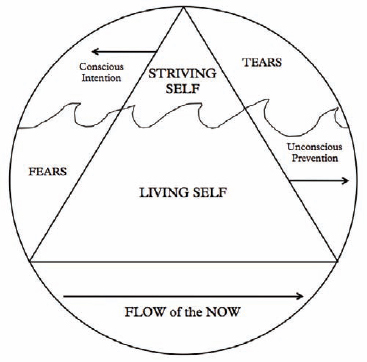

“Do you exert yourself excessively? Never. Rarely. Sometimes. Often. Always. (Circle one.)” Question number 89: “Are you the kind of person who âoverdoes' it? Never. Rarely. Sometimes. Often. Always. (Circle one.)”) He drew beautifully absurd diagrams of abstract ideas or psychological entities that were simply not susceptible to pictorial representation, and chuckled happily over them:

So (some of my readers may be forgiven for wondering), if

Letting Go

was written as a parody, a jokeâthen Jim Bird is a fraud? All his bestselling books, and the lucrative seminars spun off from them, are just a big hoax?

Not so fast, buster.

It is true that, soon after Bird sent the manuscript off to his agent, the joyous inspiration of composition faded and he ceased to think very highly of the project. It had been a distraction when

he had needed one. It had siphoned off some of the anger he felt towards his wife. It had been, he supposed, a kind of primal-scream therapy. But now, in the deafening silence with which his agent received the manuscript, Bird felt acutely embarrassed by his cathartic howls. A person's respect for their own accomplishments is usually proportionate to their efforts; because Bird had not experienced any labor pains, he could not feel as though he had given birth. The manuscript was not his child, but something he had sloughed off. He had produced it as he grew hair, and once one's hair becomes detached from one's head, one tends to view it with disgust.

His agent, a broker of scholarly monographs to university presses, understandably did not know what to make of the manuscript. Whether or not it was intended as a joke, she did not think it was likely to help her client's academic career. So she sat on it, and did nothing. When, a year later, Bird wrote to ask if he could shop it around to publishers himself, she readily consented. (Later still, when the book appeared and soon shot to the #1 spot on the

New York Times

“advice” bestseller list, where it would stay for seventeen weeks, she casually consulted her lawyer to find out if she might still be contractually entitled to some of the royalties. She was told that it would depend on whether or not Bird had kept a copy of her consenting letter. The agent decided not to pursue the matter; instead, to savor the delicious sense of having been wronged, she annulled her contract with Bird herself.)

For a year, Bird was content to leave the book alone. But when he finally picked it up and read through it again, he was surprised. Because he had had time to forget much of it, and because it was not written in his usual labored style, he found that he could almost read it as the work of someone elseâwhich is, of course, the best possible way to read one's own work.

It was undeniably silly, and dumb, and sloppily writtenâbut then, he thought, so were all self-help books. And this

was

undeniably a self-help book.

But this one was different. This one said something he agreed with. This author, he felt, had gotten something right.

You are (this author wrote) a piece of fate. Your body and your mind are governed by physical laws and necessities. That means you yourself are a law and a necessity. To improve yourselfâto

change

yourselfâit would be necessary to change the laws and necessities of the physical universe!

Because you think you should be able to improve yourself, you feel pain and anguish when you fail to do so. You beat yourself up for not being better, for not being different. But NO ONE is to blame for who they are or who they are not!

Hating yourself for not being someone else is like hating a rock for being a rock. It's not

being you

that makes you unhappy, it's

wanting to be someone else.

You are who you are. You can't be anyone else. Why would you want to be?

This, to Jim Bird, sounded familiar, and true. He had, it seemed, almost despite himself, written something of value. It was not a spoof, but an antidote.

When he sent the manuscript to several of the most prominent publishers of self-help books, he did so with some lingering shame (which was not much alleviated by signing his cover letters “Jim Bird” instead of “James R. Bird, Ph.D.”). He still feared, at this point, that someone would see through him, would see that he was only joking. This fear finally began to diminish when the book was enthusiastically accepted by a large and powerful publishing house. It diminished further when the book was launched, and still further when it began to

sell in astounding numbers. No one called him a fraud. No one said, “But you're just a philosophy professor at a cut-rate university. What do

you

know?” On the contrary, letters began to pour in from across the country assuring him that he had said something true, something of value. He began, naturally enough, to believe it. He resigned his tenure at the university. He began to receive, and then to accept invitations to speak in public, to sign books, to be interviewed on television. He started to plan a second book, one that would rectify the flaws of the first, clear up some of his readers' misconceptions, and forestall further misreadings. By the time his ex-wife accosted him after one of his sold-out lectures, the feeling that he would be exposed as a sham had been almost completely extinguished.