Purple Cow (12 page)

Case Study: How Dutch Boy Stirred Up the Paint Business

It’s so simple it’s scary. They changed the can.

Paint cans are heavy, hard to carry, hard to close, hard to open, hard to pour from, and no fun. Yet they’ve been around for a long time, and most people assumed there had to be a reason.

Dutch Boy realized that there was no reason. They also realized that the can was an integral part of the product—people don’t buy paint; they buy painted walls, and the can makes the painting process much easier.

Dutch Boy used this insight and introduced an easier-to-carry, easier-to-pour-from, easier-to-close paint jug. Sales went way up—no surprise when you think about it. Not only did the new packaging increase sales, but it also got Dutch Boy paint more distribution (at a higher retail price!).

A few obvious changes in the can meant a huge surge in sales for Dutch Boy. The obvious question: Why did it take so long?

This is marketing done right. Marketing where the marketer changes the product, not the ads.

Where does your product end and marketing hype begin? The Dutch Boy can is clearly product, not hype. Can you redefine what you sell in a similar way?

Case Study: Krispy Kreme

There are two kinds of people—those who have heard the legend of Krispy Kreme donuts and assume that everyone knows it, and those who live somewhere where the donut dynasty hasn’t yet shown up.

Krispy Kreme makes a good donut. No doubt about it. But is it a donut worth driving an hour for? Apparently, donut maniacs believe it is. And this very remarkable fact is at the core of Krispy Kreme’s success.

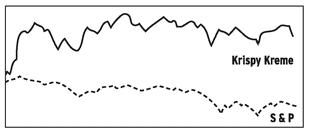

Since the day of their IPO, Krispy Kreme has totally demolished all expectations, drastically outperforming just about every other stock. Why? Krispy Kreme understands how to manage the Cow.

When Krispy Kreme opens in a new town, they begin by giving away thousands of donuts. Of course, the people most likely to show up for a free hot donut are those who have heard the legend of Krispy Kreme and are delighted that they’re finally in town.

These sneezers are quick to tell their friends, sell their friends, even drag their friends to a store. And that’s where the second phase kicks in. Krispy Kreme is obsessed with dominating the donut conversation. Once they’ve opened their flagship stores in an area, they rush to do deals with gas stations, coffee shops, and delis. The goal? To make it easy for someone to stumble onto the product. They start with people who will drive twenty miles, and finish with people too lazy to cross the street.

If the product stays remarkable (and Krispy Kreme is betting millions that it will), then some of those lazy people will be converted to the donut

otaku.

They will start the next wave of Krispy Kreme mania, spreading it in a new town until the chain arrives.

otaku.

They will start the next wave of Krispy Kreme mania, spreading it in a new town until the chain arrives.

It’s worth noting that this probably wouldn’t work with bagels or brownies. There’s something very visceral about the obsession that donut fans feel about Krispy Kreme, and discovering and leveraging that feeling is at the heart of this phenomenon. In other words, find the market niche first, and then make the remarkable product—not the other way around.

The Process and the Plan

So is there a foolproof way to create a Purple Cow every time? Is there a secret formula, a ritual, an incantation that you can use to increase creativity at the same time you stay firmly grounded in reality?

Of course not.

There is no plan. The eventual slowdown of almost every Purple Cow company indicates that there’s no rule book listing things that always produce. That’s one reason that seeing the insight of the Cow is so difficult. Looking in our rear-view mirror, we can always say, “Of course that worked.” By definition, a genuine Purple Cow is something that was remarkable in just the right way. When we take our eyes off the rear-view mirror, though, creating a Purple Cow suddenly gets a lot more difficult.

If you were looking to this book for a plan, I’m sorry to tell you that I don’t have one. I do, however, have a process. A system that has no given tactics but is as good as any.

The system is pretty simple: Go for the edges. Challenge yourself and your team to describe what those edges are (not that you’d actually go there), and then test which edge is most likely to deliver the marketing and financial results you seek.

By reviewing every other

P

—your pricing, your packaging, and so forth—you sketch out where your edges are... and where your competition is. Without understanding this landscape, you can’t go to the next step and figure out which innovation you can support.

P

—your pricing, your packaging, and so forth—you sketch out where your edges are... and where your competition is. Without understanding this landscape, you can’t go to the next step and figure out which innovation you can support.

Would it be remarkable if your spa offered all its services for free? Sure, but without a financial model that supports that, it’s not clear that you’d last very long. JetBlue figured out how to get way over to the edge of both service and pricing—with a business that was also profitable. Archie McPhee did it in retail with their product selection. Starbucks determined how to redefine what a cup of coffee meant (in a way very different from the way JetBlue delivered their innovation).

It’s not the tactics or the plan that joins the Purple Cow products together. It’s the process organizations use to discover (intentionally or accidentally) the fringes that make their products remarkable.

The Power of a Slogan

Slogans used to be important because you could put them in TV commercials and get your message across in just a few seconds. Today, that same conciseness is important but for a different reason.

A slogan that accurately conveys the essence of your Purple Cow is a script. A script for the sneezer to use when she talks with her friends. The slogan reminds the user, “Here’s why it’s worth recommending us; here’s why your friends and colleagues will be glad you told them about us.” And best of all, the script guarantees that the word of mouth is passed on properly—that the prospect is coming to you for the right reason.

Tiffany’s blue box is a slogan without words. It stands for elegance and packaging and quality and “price is no object.” Every time someone gives a gift in the Tiffany’s box, she’s spreading the word. Just like the Hooters name and logo or the funky hipness of Apple’s industrial design, each company has managed to position itself in a coherent way and make it easy to spread the word to others.

The Leaning Tower of Pisa sees millions of visitors every year. It’s exactly as advertised. It’s a leaning tower. There’s nothing to complicate the message. There’s no “also,” “and,” or “plus.” It’s just the leaning tower in the middle of a lawn. Put a picture on a T-shirt, and the message is easily sent and received. The purity of the message makes it even more remarkable. It’s easy to tell someone about the Leaning Tower. Much harder to tell them about the Pantheon in Rome. So, even though the Pantheon is beautiful, breathtaking, and important, it sees 1 percent of the crowds that the harder-to-get-to Tower in Pisa gets.

Every one of these examples highlights the fact that this is not marketing done to a product. The marketing is the product, and vice versa. No smart marketer transformed Hooters or the Leaning Tower of Pisa. The marketing is built right in.

Do you have a slogan or positioning statement or remarkable boast that’s actually true?

Is

it consistent? Is it worth passing on?

Case Study: The Häagen-Dazs in Bronxville

The nearest Häagen-Dazs is just like all the other ice cream shops you’ve been to. They’ve got cones, bars, and frozen yogurt. Only two things are different about a Häagen-Dazs shop: it’s cleaner and a lot better run. How come?

Well, sitting on the counter is a stack of large business cards. The card lists the name and office phone number of the owner of the store. And then the card says, “If you have any comments at all about the store, please call me at home.” And it lists the owner’s home phone number.

People who visit, notice. People who work there realize that the customers are noticing. It’s all very remarkable. Stand in the store for twenty minutes, and you’re sure to hear one customer mention the cards to another. If every store owner did this, it probably wouldn’t work. But because it’s so unusual, the customers take notice and the staff is on alert.

If you’re in an intangibles business, your business card is a big part of what you sell. What if everyone in your company had to carry a second business card? Something that actually sold them (and you). Something remarkable. Imagine if Milton Glaser or Chip Kidd designed something worth passing on. So go do it!

Other books

Psi Another Day (Psi Fighter Academy) by D.R. Rosensteel

Treasures, Demons, and Other Black Magic by Meghan Ciana Doidge

Fire Kin by M.J. Scott

Handle with Care by Porterfield, Emily

Electra by Kerry Greenwood

Bad Behavior #1: Tales of an American Gigolo by Childers Lewis

Sweet Harmonies by Melanie Shawn

Plush Book 2: A Billionaire Romance by Winters, KB

The Nameless Hero by Lee Bacon

Reunion by Jennifer Fallon