Qatar: Small State, Big Politics (24 page)

Read Qatar: Small State, Big Politics Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

But does power, or, more specifically in this context, state capacity, also mean complete state autonomy? It is this question that is the topic of the next chapter.

5

S

TATE

C

APACITY AND

H

IGH

M

ODERNISM

A critical factor in the Qatari state’s ability to pursue its international and regional agendas is its considerable capacity in relation to society. In fact, the state has pursued domestic social engineering—an ambitious project of “high modernism”—with the same enthusiasm and determination characterizing its foreign policy behavior. In the process, the state has managed to expand and deepen its ties with important social actors and to bring them into its orbit through forging lucrative financial ties, maintain and enhance its own autonomy and its domestic and international maneuverability, and to continuously expand its capacities to pursue ambitious developmental agendas.

State capacity and autonomy are two key ingredients of developmental states. Whereas capacity is the general ability to articulate and implement developmental agendas, autonomy rests in the state’s ability to “formulate and pursue goals that are not simply reflective of the demands or interests of social groups, classes, or interests.”

1

I argue that in the past decade the Qatari state has been able to maximize both its capacity and its autonomy, having in the process become a successful developmental state. Moreover, through reliance on publicly owned real estate companies, the state has, on the one hand, pursued a project of high modernism while, on the other hand, deepened the dependence of social actors and private capital on itself. Augmentation of state capacity and political consolidation have gone hand in hand, with the state both penetrative of and densely linked with society. What domestic constraints there are on the state are of a relatively minor nature and are not sufficient to necessitate course alterations or even meaningful concessions to social actors.

Building on the arguments of the previous chapter on the consolidation of Al Thani rule, the chapter begins with an examination of the financial resources at the disposal of the Qatari state and the resulting, ambitious infrastructural projects that have dramatically changed Qatar’s physical landscape over the past few years. Doing so has required considerable capacity on the part of the state, broadly defined as its ability to meaningfully penetrate the various levels of society and to carry out its transformative, developmental agendas with great success. The primary vehicles for the country’s phenomenal growth have been publicly owned corporations, almost all highly profitable, and all used as important vehicles for the incorporation of technocrats and other skilled members of the middle and upper classes into the orbit of the state. An important resulting consequence has been a deepening embeddedness of the state in society and the expansion of its linkages with social actors. The domestic stability of the Qatari state rests not just in the consolidation of Al Thani rule. Just as significantly, it derives from expansive and deepening commercial and institutional linkages with society. A mutually reinforcing and empowering relationship develops between state and society in which the state relies on its societal allies to carry out its manifold developmental agendas, while social actors rely on the state for a continuation of their economic status and enrichment.

The chapter then examines the capacity of the Qatari state in relation to Qatari society. It looks in particular at the state’s efforts to bring about what James C. Scott has termed “high modernism.” It specifically explores the state’s efforts to create a parallel, alternate reality with its projects of modernism. That these projects have little resemblance to anything remotely Qatari, and that they often directly undermine and contradict the state’s own vibrant heritage industry efforts, matter little. The state is determined to modernize Qatari society—to rationalize and to upgrade its life through the creation of futuristic cities and public spaces—and it claims to be doing so while simultaneously preserving Qatari tradition.

Change is never easy and is often accompanied by a certain degree of unease and discomfort. Rapid and profound social change can have particularly destabilizing effects in dictatorships with few or no outlets for public debate and discussion. The state remains autocratic and allows for no dissent. But its intolerance appears to be more a product of dictatorships’ knee-jerk reaction to any signs of nonconformity rather than the existence of widespread dissent in Qatari society. In fact, political dissent in Qatar is relatively benign, a product of inordinate wealth, supported by carefully crafted state policies. The outcome, ultimately, is a state with tremendous capacity to foster development and an insatiable appetite for reaching for the stars.

State Capacity and Autonomy

The ability of the Qatari state to engage in its domestic and international endeavors with the same level of zeal and enthusiasm is sustained and reinforced through two mechanisms: the massive revenues accrued by the state through the sale of hydrocarbons, and the cohesion of the ruling elite. A member of OPEC, Qatar is an important producer and supplier of oil. Compared to other OPEC members, however, it is not a major player in the global oil markets. With its oil production at 1,569,000 barrels per day (bpd) at the end of 2010 (1.7 percent of total), it ranks far below Saud Arabia (10,007,000 bpd; 12 percent of total), Iran (4,245,000 bpd; 5.2 percent of total), the United Arab Emirates (UAE: 2,845,000 bpd; 3.3 percent of total), and Iraq and Kuwait (each with approximately 2,500,000 bpd; 3.1 percent of total).

2

But what Qatar lacks in terms of oil reserves and production, it more than makes up for in natural gas. In fact, starting in 2007 Qatar began earning more from gas exports than from oil exports. The country has the world’s third largest reserves of natural gas (13.5 percent of total), after Russia and Iran (with 23.9 and 15.8 percent of global total each), and is the world’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas. In 2010, Qatar produced some 116.7 billion cubic meters of LNG, almost all of which was exported and brought the country billions in earnings.

3

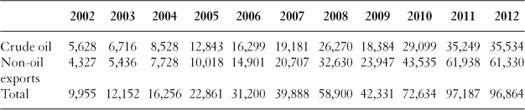

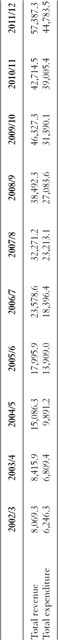

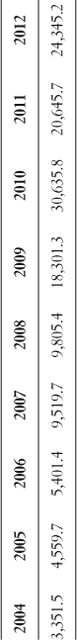

The financial windfalls resulting from Qatar’s oil and gas sales are considerable by any standard, but all the more so given the small scale of the society over which the state rules. As the data in

tables 5.1

–

5.4

indicates, from 2002 to 2012, Qatar’s oil and gas exports saw an increase of more than 631 percent, to a total of $98.8 billion. From 2002/3 to 2011/12, the state’s revenues increased by 711 percent, shooting up from $8.1 billion to approximately $57.3 billion. State expenditures in the same period grew by 717 percent, from $6.2 billion to $44.8 billion. From 2004 to 2012 the foreign assets of the country’s Central Bank saw an increase of over 726 percent to over $24 billion. Qatar’s nominal gross domestic product was reported at a $172 billion in 2011, equating to 2.5 percent of global GDP and 12.5 percent of the countries of Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).

4

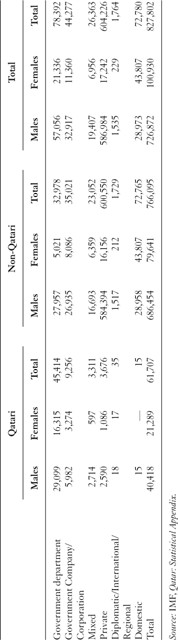

In the meanwhile, the state has had to support a workforce of no more than about 149,000 at most, about half of which worked for mixed venture companies with private sector partners.

On top of the reserves accrued from the sale of oil and gas, the Qatari government has access to additional revenue streams resulting from its multiple domestic and international investments. The actual size of Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund, similar to most others across the GCC, is a closely guarded secret and is therefore difficult to determine with great accuracy.

5

However, as of 2012 it was generally estimated at approximately $85 billion,

6

with stakes in companies, banks, and various development projects in Asia, North America, and Europe, including the London Stock Exchange, Volkswagen, Sainsbury supermarkets, and the Harrods Group. Established in 2005, the primary objective of the Qatar Investment Authority is to diversify the state’s revenue sources and to mitigate the risks associated with the country’s reliance on global energy markets.

7

As such, most of its domestic and international investments are outside of the energy sector. Although the rate of return on these global investments is difficult to determine, they do provide a significant source of funds for the state that further enrich its coffers and enables it to act as an important actor on the global stage.

TABLE 5.1.

Qatar’s select economic indicators: Hydrocarbon exports (millions of USD)

TABLE 5.2.

Qatar’s select economic indicators: Government revenues and expenditure, 2002/3-2011/12 (millions of US)

TABLE 5.3.

Qatar’s select economic indicators: Foreign assets of Qatar Central Bank (millions of USD)

TABLE 5.4.

Qatar’s select economic indicators: Economically active population by nationality, gender, and sector (October 2007)

All of this has amounted to the country’s phenomenal growth in recent years. According to the Institute for International Finance (IIF), Qatar’s economy grew at 18.8 and 18 percent in 2010 and 2011, respectively.

8

Accordingly, Qatar is witnessing an unprecedented building bonanza. Estimates of the government’s projected expenditure on infrastructure in the 2011–2016 period vary from $150 billion to $225 billion.

9

In the first half of 2011, Qatar was estimated to have a budget surplus of $13.7 billion.

10

The Qatar Stock Exchange also saw a 20 percent rise in its value during the same period.

11

By late 2011, international financial analysts were proclaiming Doha rather than Dubai as the region’s preeminent financial hub.

12

In 2012, for the second year in a row, a global survey found Qatar to have the most innovative economy in the GCC, placing it a respectable thirty-third out of a total of 141 countries surveyed.

13

Although the IIF estimates that the growth will decelerate to 6 percent in 2012 and then to 4 percent in 2013, the country’s massive growth and infrastructural development is expected to continue in the foreseeable future. In fact, as a confident sign of more good times yet to come, in 2011, the Ezdan Real Estate Company, one of the country’s oldest publicly owned companies with 2010 profits in excess of $33 million and assets of $8.7 billion, announced plans for building the world’s largest tower in Doha.

14