Quarterly Essay 58 Blood Year: Terror and the Islamic State (21 page)

Read Quarterly Essay 58 Blood Year: Terror and the Islamic State Online

Authors: David Kilcullen

If the home-based palliative care, nursing and GP services Ian Maddocks describes were available in all regions, and if everyone had ready access to a few thousand dollars a week, then many more would be able to die at home. The choice would

truly

exist. And it would be a good thing.

We know what the goal of a hospital admission is: to get people well, if possible, and out of the hospital. What is the goal of a nursing home? To care for someone until they die. But what does “to care for someone” actually mean? Inga Clendinnen ignores my caveats and takes me to task on some of my comments about nursing homes. These comments are neither anecdote nor opinion. They are points of fact: there is a vast shortage of adequately trained staff, half of Australian aged-care residents are on psychotropic medications, direct sunshine on the face is rare. The average-sized nursing home has between 100 and 200 residents. Some house up to 400 people. Peaceful nursing-home deaths are possible, but only if staff are skilled and supported. In this way they are as much dependent on “determined nurses” – and an institution’s culture – as the hospital death of which I wrote. It is exactly as Clendinnen states: “The essence of the place comes down to a few nurses.” Not every place has such nurses.

If all nursing homes were like Clendinnen’s, no family would feel guilty and fewer people would be reluctant to enter them. Not everyone has a long list to choose from, nor the funds, wherewithal or discernment to choose; some must go to places to which (in the words of a social worker I know) “you wouldn’t send a stray dog.”

Clendinnen asks why my mother did not “raise Cain” about my great-aunt’s unclipped nails and soiled dressing-gown. One might just as well ask why the abused do not leave their abusers. Power, in the first instance. People fear retribution. But she did in fact complain. Repeatedly. What often happens when a complaint is lodged with an institution? It spurs a great chain of instant action: it is converted to words on a computer, emailed and reviewed; boxes are ticked; files are made; it is responded to “administrivially” – and nothing is changed. State authorities don’t have time to investigate the lack of podiatry services and intervene. They are dealing with suicide, assault, gross neglect and starvation. Read the literature, call the coroners, bless the oasis in which you live.

In highlighting the severe lack of community supports for those who wish to stay in their own home, I am not advocating that we “force women into cruel servitude” to care for their elderly relatives. What I seek is greater support for the many who do wish to remain at home; greater support for those who do wish to care for their parents; appreciation that this care is not merely a “cruel servitude” but can be a mutually valuable and meaningful act of love. We leave the world as we enter it – needing assistance. In some societies in the past, children were not named until they were five years old. They did not enter personhood until then, as the odds of living were stacked against them. Who are the anonymous now?

Clendinnen disagrees that we can at times ask for the opposite of what we wish for, and states that she wants to be obeyed when she decides she wants to die. And yet she tells us of exactly such a situation, and how the neurologist immediately agreed – no doubt indoctrinated to “respect patient choices.” This neurologist had no understanding that – as Komesaroff points out – “A statement supposedly rejecting a specific treatment might in reality be an expression of vulnerability, uncertainty and fear.” How lucky she was to have had another doctor, one who cared enough to do more than simply “respect her human rights” and obey her statement as if they were two computers communicating in an indisputable and unambiguous binary. He talked with her, listened to her, asked her to give him three weeks – which has enabled her to give us all so very much.

Susan Ryan attempts to reduce my essay to a kind of vanity project with me as hero. In contradistinction to this, she states: “What I am advocating – rather than just hoping for the rescue doctor to appear at the end – is dealing with ageism in all its forms, including in hospitals.” I can only conclude that she must not have read

Dear Life

. Her solution is to embed a human-rights approach in all services and institutions. Unfortunately, her description of a human-rights approach looks like more of the same: protocols and forms, directives and the instrumentalisation of human interaction. Dignity, respect and choice: a handful of catchphrases now empty of meaning and coopted into a rationalistic, bureaucratic, managerial approach to rationed “service provision” that always ends with how and when and by whose hand we will die. Our “human rights” appear to have shrunk to a signed sheet of paper that protects us from non-death. This is inaction disguised as action in the face of an entrenched and pervasive ageism.

I was lying in bed a few nights ago; it was late, I was semi-conscious, and an ambulance shot past, sirens blaring, pushing urgently through the night. And I started to think about ambulances and all they tell us about our community’s attitude towards life, towards health. An ambulance approaches and cars stop, people turn, the neighbourhood awakens, parents momentarily feel a slim wedge of terror. Someone wakes sick in the night and with a single phone call a state emergency vehicle is mobilised to bring them to a hospital all lit up and ready to receive them. Doctors will listen to their story, examine them, fix them or reassure them or alleviate their suffering. The hospital will receive them, no matter who they are. This – we believe – is a “human right.” And yet when Clendinnen called an ambulance for her husband, the paramedics “flatly refused to take him to hospital. I was incredulous; they were firm. So were the team I called the next day. Then it was the weekend, both sons were away, the ‘Doctor on Call’ had no power to do anything.” What a pity, Ryan might counter, that her husband had not acted on his “human right to have an advanced care directive.” It would have saved them the trip.

Karen Hitchcock

Inga Clendinnen

’s Quarterly Essay,

The History Question: Who Owns the Past?

, appeared in 2006. Her ABC Boyer Lectures,

True Stories

, were published in 2000, as was her award-winning memoir,

Tiger’s Eye

. In 2003

Dancing with Strangers

attracted wide critical acclaim. Her most recent book is

The Cost of Courage in Aztec Society

.

Stephen Duckett

is Director of the Health Program at Grattan Institute. He is the co-author, with Hal Swerissen, on a recent report on end-of-life care,

Dying Well

.

Karen Hitchcock

is the author of the award-winning story collection

Little White Slips

and a regular contributor to

The Monthly

. She is also a staff physician in acute and general medicine at a large city public hospital.

Leah Kaminsky

, a physician and writer, is poetry and fiction editor at the

Medical Journal of Australia

. She edited

Writer MD

, a collection of prominent physician-writers, and is the author of

Cracking the Code with the Damiani Family

. Forthcoming are her debut novel,

The Waiting Room

, and a non-fiction book about death denial.

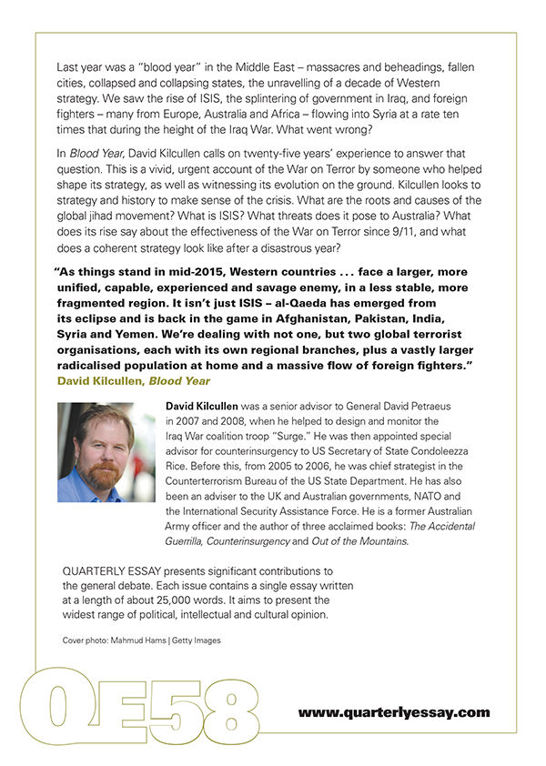

David Kilcullen

was a senior advisor to General David Petraeus in 2007 and 2008, when he helped to design and monitor the Iraq War coalition troop “Surge.” He was then appointed special advisor for counterinsurgency to US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. Before this, from 2005 to 2006, he was chief strategist in the Counterterrorism Bureau of the US State Department. He has also been an adviser to the UK and Australian governments, NATO and the International Security Assistance Force. He is a former Australian Army officer and the author of three acclaimed books:

The Accidental Guerrilla

,

Counterinsurgency

and

Out of the Mountains

.

Paul Komesaroff

is a physician and philosopher at Monash University and Director of the Centre for Ethics in Medicine and Society. He is the author of

Experiments in Love and Death

and

Riding a Crocodile: A Physician’s Tale

.

Jack Kirszenblat

is a psychiatrist to the cancer services at the Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, and also works in private practice.

Ian Maddocks

taught medicine in Papua for fourteen years, and at Flinders University from 1975 to 1999, becoming Professor of Palliative Care there in 1988. He was Senior Australian of the Year in 2013.

Peter Martin

is the

Age

’s economics editor. A former ABC economics correspondent and Commonwealth Treasury official, he has been writing about economics since 1985.

Leanne Rowe

is a general practitioner, and past chair of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners.

Susan Ryan

is the Age and Disability Discrimination Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission. She was Senator for the ACT from 1975 to 1988 and served as Minister for Education and Youth Affairs, Minister Assisting the Prime Minister on the Status of Women and Special Minister of State.

Rodney Syme

was an urologist at the Austin and Repatriation Hospitals from 1969 to 2002. He is a longstanding advocate for physician-assisted dying and the author of

A Good Death

.

Table of Contents