Queen of the Oddballs (3 page)

Read Queen of the Oddballs Online

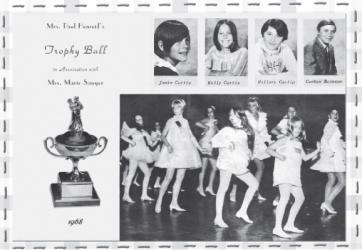

Authors: Hillary Carlip

The displeasure was not restricted to our table, and I could feel the tension in the room grow as thick as Mrs. Marie Sawyer’s hairspray. I felt like we were in

West Side Story

—the Curtis/Leigh, Heston, Price, and Landon kids were the Sharks, and the rest of the just-plain folks, the Jets. And I didn’t even figure into this dance-off. I was the tomboy, Anybodys. Or, more aptly,

Nobodys

. By the time the cha-cha competition ended and Jack Benny’s grandson won first place—Mrs. Atkins blurting, “But he can’t even dance!”—I was sure I was going to see an uprising. And judging by my father’s lip, which was by now so curled it completely obscured his mouth and made him look like a sideshow freak, I knew who would be leading the rebellion. I just didn’t know

how

. I couldn’t decide whether to excuse myself and hide out in the ladies room or stay and try to calm my father down.

Then Mrs. Marie Sawyer leaned into the microphone. “We have one last competition not listed in your souvenir program. In honor of tonight’s theme, we have a surprise category called the Father/Daughter Freestyle! Fathers, daughters, hit the floor, it’s time to dance!”

“Come on,” my dad snapped, grabbing my gloved hand. “We’ll show them all.”

Oh. No.

He dragged me to the dance floor and started to let loose. And I mean

loose

. Dad was not dancing the way the stars or even the Beverly Hills socialites danced. My dad was

feeling

the music. Eyes closed, he began to gyrate and spin, offering up interpretive dance moves as if he were listening to the Rolling Stones instead of Tony Bennett. Dancing with abandon, fingers snapping, arms flailing to the beat, he was groovy, man.

I looked up and saw everyone staring at us. The Hestons. The Landons. Even Janet Leigh. A few people pointed. Some laughed.

Then suddenly, the dancers on the floor stepped aside—just the way they did on

American Bandstand

when a featured dancer began doing some killer moves. My father twirled me into the middle like I was one of the

Jackie Gleason Show

’s June Taylor Dancers. I did my best to keep up with him, but there was no hope. Despite my total ineptitude, my father’s carefree attitude seemed to be infectious. People began to clap along. I was so utterly mortified, I was ready to fling myself off a balcony into the deep end of the Beverly Hilton swimming pool. I swore then and there that I would never speak to my father again.

Never.

The song finally ended. My dad’s lip had unfurled, and he was smiling, in his glory, as the crowd went wild with applause.

“Well, wasn’t that something?” Mrs. Sawyer called out over the microphone. The judges whispered in her ear, and she announced, “I guess there’s no question who wins first-prize trophy for the Father Daughter Freestyle dance. Hillary Carlip and her father, Bob Carlip, congratulations!”

I floated out of my body. Instead of standing in the spotlight of attention, I imagined myself sitting next to my first choice for a partner, Kelly Curtis, casually sipping Shirley Temples, laughing and discussing how embarrassing parents can be.

Flashbulbs popped, bringing me back. And there I was, holding a trophy.

Me.

My father gripped my other hand and held it high in the air. And I let him. I smiled at Dad, sharing our victory.

As Mrs. Henreid and Mrs. Sawyer bid everyone “Adieu, till next year,” classmates came up to me saying things like, “Wow!” and “That was something!” My fat, sweaty partner put out his hand to shake mine. “Thanks, you really showed them all.” And then Darby Hinton came up to me, too. “That was really cool.”

Not only had my dad saved the day for the everyman and every-woman in the room that night, he had also upped my credibility. Maybe, I thought, I’d never again be the one picked last. Maybe now I would dance with a handsome TA or a dreamy child star. Maybe I could even have a say in things and insist, “Girls and girls or boys and boys can dance together.”

But wait a minute…if I wanted all that, I’d have to come back to cotillion next year. Well, I thought, as we drove home into the suddenly sweet night, if someone has to kick the Goulets’ and Montalbans’ asses, it might as well be me.

1971

- Though Happy Face buttons hit their peak of popularity with more than fifty million sold, the button I wear says: “Impeach Tricky Dick.”

- I hang out with my good friend Brina Gehry at her cookie-cutter, suburban home in Westwood while her father, Frank, is off working—though I don’t even know what he does for a living.

- Most kids in my school wear Frye boots, gauchos, ponchos, and puka shells. I wear peasant blouses, army jackets, Earth Shoes, and a halter top I make out of an American flag, which provokes many strangers on the street to scream at me, calling me unpatriotic.

- My working mother discovers the newly introduced Hamburger Helper and couldn’t be more thrilled.

- At a Grateful Dead concert in San Francisco, more than thirty fans go to the hospital after unknowingly drinking apple juice laced with LSD. Meanwhile, I smoke a joint with a friend that we find out later was laced with PCP, and I end up passed out in an alley, hallucinating the head of my dead grandfather, whom I never met, flying around on wings.

- After he’s my classmate for a short stint at Emerson Junior High, Michael Jackson has his first solo hit single, “Got to Be There.”

M

usic helped drown out the dissonance of my adolescence. I’d climb out to the roof from my second-story bedroom window and blast Cat Stevens’s “Wild World” so I wouldn’t have to hear my brother constantly arguing with my parents. I’d listen to Laura Nyro’s “Lonely Women” so I would stop thinking about the boys who didn’t like me, and to Joni Mitchell’s “I Don’t Know Where I Stand” to forget the twenty-two pounds I lost and had rapidly gained back, plus ten.

After a while, the records weren’t enough. That’s when I began frequenting the Troubadour, the hottest nightclub in seventies L.A.

The “Troub,” as we regulars called it, was an intimate joint where the great singer-songwriters performed two shows a night, six nights a week. I saw Joni Mitchell, Bonnie Raitt, James Taylor, Laura Nyro, and even Elton John, whose sweat dripped onto my arm as I watched from a table right under the stage. It didn’t matter that I was only fourteen years old—no one at the Troub ever checked IDs.

One warm April night, the scent of honeysuckle drenching the air, my friend Molly and I hitchhiked to the Troub to hear Cat Stevens. First in line, I caught my reflection in the window of the martial arts studio next door to the club. Dressed in my favorite thrift store outfit—embroidered peasant blouse, patched bell-bottom jeans, and a long fifties-style blue wool coat that I rarely took off—I actually felt uncharacteristically attractive. Well, until I spotted Molly’s reflection next to me—blonder, a foot taller, and much shapelier in a halter top than I.

Once inside the club Molly and I grabbed one of the front tables, ordered bubbly ginger ales, and sipped them through pink cocktail straws. Nobody, including us, had ever heard of the opening act—a lanky, tall woman who sauntered onto the stage with a guitar, followed by her backup band, three guys with a lot of hair.

An announcer spoke over the PA. “Ladies and gentlemen, please give a warm welcome to new Elektra recording artist, Miss Carly Simon.”

The singer’s voice was rich, deep, and intoxicating, her smile so broad it lit up like an angelic jack-o’-lantern. I knew immediately that this woman was different from all the other girl singers. Her lyrics were defiant: “

You say we’ll soar like two birds through the clouds, but soon you’ll cage me on your shelf. I’ll never learn to be just me first, by myself.”

I had goose bumps. Carly captivated me. I knew I had to return for the next five nights. I knew I would meet Carly Simon. No, I wouldn’t just meet her.

I would befriend Carly Simon.

When the show was over and we were filing out of the club, the only teenagers in a sea of adults, I grabbed Molly’s arm. “Come on,” I whispered, dragging her up a set of narrow, carpeted stairs. Without question Molly followed, playing Ethel to my Lucy.

At the top of the stairs, I found what I was looking for: Taped to one of two paint-splattered doors was a yellow scrap of paper with Carly’s name scrawled on it in ballpoint pen.

I knocked tentatively.

The door swung open, and there she stood, towering over me, tall and graceful, wearing a long paisley dress and brown lace-up boots. “Yes?” she asked in that lush, resonant voice.

I nearly fell over backwards. “Uh, hi. We just wanted to tell you how amazingly talented you are.” Shit. That sounded stupid—like something a

fan

would say.

I quickly added, “And you’re a true artist.”

Much better. Weightier.

Carly beamed. “Well, thank you. You girls want to come in?”

“Sure,” I stuttered, surprised by the invitation—especially after my lame opening.

We stepped into clouds of cigarette smoke that nearly obscured our view of the three band members crammed into the tiny space. The pianist, a skinny man with a ponytail that spilled down his back, moved over to make room for us on a ratty, plaid couch. We squeezed in between him and the drummer, who was dabbing his damp head full of curls with a paper towel. “So, you guys like the show?” he asked.

“Are you kidding? It was fantastic,” I yipped, then toned it down. “You’re all very talented.”

“Yeah,” Molly added.

Carly looked right at me. “I want to know what you

really

think. Good or bad. Be honest.”

Oh my God. Someone wanted to know what I

really

thought. I had better come up with something good. “Well…” I began hesitantly, “your songs are moving, your voice gorgeous, and the band’s fantastic. My only criticism is that it’s hard to hear your voice on some of the more upbeat songs. Maybe they need to turn up your vocal mic?”

Carly smiled, those full lips spreading across her face. “Excellent point. So, do you girls go to a lot of concerts? What kinds of music do you like?”

I was blown away. Most adults asked the same idiotic questions: How old are you? What’s your favorite subject in school? What do you want to be when you grow up? But not my new friend Carly.

“I like female singer-songwriters. Joni Mitchell, Laura Nyro.”

“Janis Joplin,” Molly added.

“You guys have great taste,” Carly said, smiling that smile again.

We hung out for more than a half hour, chatting with Carly and the band. When the guitarist with the muttonchop sideburns began to organize his gear for the second set, we stood up to leave. “We gonna see you again this week?” he asked.

“Sure, definitely.” I said.

“Definitely,” Molly echoed.

“Good,” Carly said.

It was a solid good. Like she meant it. Then, at the door, Carly Simon

hugged

me.

We floated out of the club and onto Santa Monica Boulevard, nonchalantly walking past the martial arts studio, then across Doheny. It wasn’t until we reached a small, secluded park where we were certain no one could see or hear us that we both finally let loose our screams.

“Oh. My. God. That was surreal!” I slalomed through a line of trees, then flopped onto the grass and rolled around in circles.

“I can’t believe you just knocked on her door,” Molly shouted, “and that she invited us in!”

“Watch,” I said, “she’s gonna be a huge star. I just know it.”

I didn’t want to go home yet, back to my solitary bedroom, my ordinary existence where no one asked questions that mattered.

The next day, trapped in my beige stucco junior high school, I couldn’t concentrate. I kept replaying the night before, anticipating what would happen

this

night. How excited Carly would be to see me. How we’d sit on the couch together, talking about music, art, literature, philosophy.

Yeah, right. Who was I kidding? Why would Carly Simon want to be my friend? I would have to win her over.

The minute I got home from school, I baked banana bread as an offering for Carly and the band. That evening we arrived early at the Troub and snagged our front row table. All through the first set I held the still-warm loaf in my lap, as protectively as if it were a newborn.

At intermission, Molly and I hurried upstairs. When Carly opened the door, she grinned, and the guitarist called out, “Hey, it’s the girls!”

The girls. We were

the girls

.

I handed Carly the banana bread. She thanked me and placed it on the coffee table, next to an overflowing ashtray, and the guys immediately dug in.

“Did you notice we cranked up the vocals on the up-tempo songs?” Carly asked. “Great suggestion last night, Hillary.”

I suppressed the squeal rising in my throat. “You sounded incredible.”

I had recently added the words “incredible” and “amazing” to my vocabulary because my friend Amy’s older sister said them, and she was cool—she had a black boyfriend who played the flute.

While Cat Stevens performed downstairs, we sat on the couch joining in the conversation as Carly and the band dissected their show. When we heard the applause at the end of Cat’s first set, I stood.

“Sorry we can’t stay, but we’ll see you tomorrow night.”

The band waved, thanking us for the bread. And this time at the door, Carly Simon

kissed

me good-bye.

All that week, bringing gifts of pumpkin, date-nut, cinnamon-raisin, and honey-walnut breads, recipes courtesy of

The Tassajara Bread Book

, Molly and I hung out in Carly’s dressing room. On the third night, she added us to the guest list—a great relief, since with the $4.00 ticket price and the cost of baking ingredients, my weekly allowance was hardly enough to keep up.

On closing night, when Cat Stevens ended his set, we knew the time to say good-bye had come. My eyes welled up with tears, but I bit my lip and held them back. Be strong.

Be strong.

“Well,” I said as I headed to the door, “it was great hanging out with you guys.”

“Yeah,” Molly added. “Thanks for getting us in and all.”

Carly stood. As she leaned over to give us the good-bye hug and kiss we’d grown accustomed to, she said, “Next time I’m back, you promise to come see me?”

Was she kidding? Of course we’d come see her. What were friends for?

The next seven months dragged, the only high point being news of Carly’s success. “That’s the Way I’ve Always Heard It Should Be,” a song from her first album, rose on the charts, and just as she released her second album,

Anticipation

, we learned she was returning to the Troub. This time as the headliner.

On a rainy November opening night, armed with a loaf of three-layer corn bread, Molly and I opted for a table in the back so we could unobtrusively leave our seats during the opening act and visit Carly upstairs. A singer-songwriter named Don McLean was onstage, performing a new song called “American Pie,” when Molly and I crept to the dressing room. My heart was beating faster and harder than it had the first time I knocked on that door. After all, Carly was a star now. What if she wasn’t as welcoming as before? Worse, what if she’d forgotten us?

I took a deep breath and knocked.

The door opened a crack and a man in a dark suit gruffly said, “Yes?”

“Uh, we’re here to say hi to Carly and give her this,” I said, holding out the loaf.

“She can’t see anyone now,” he snapped, obviously thinking we were just some

fans

. He started to close the door on us, but I stuck my foot inside and shouted, “Tell her it’s Hillary and Molly!”

In an instant, Carly appeared at the door.

“It’s the girls!” she cried, and she hugged and kissed us as if those seven months had only been a moment.

She was, truly, our friend.

So again Molly and I spent a week hanging out with Carly and the band. One night, between songs, Carly looked out at the audience and said, “This one is for Hillary and Molly,” then launched into “Anticipation.” The next night she dedicated “One More Time,” and every night after that, Carly dedicated a song to us.

I had never before felt so happy. So important.

Months passed. It was on an overly smoggy summer day, at a newsstand in Westwood Village, that I spotted an interview with Carly in

Where It’s At

, a popular music magazine. I began to read, when suddenly my heart nearly stopped.

“‘At the Troubadour, it’s been great,’” Carly was quoted. “‘There are these two girls who have really just made my evenings there.’”

Fuckin’ A!

Carly was talking about me and Molly. In a magazine!

I threw money down on the counter, grabbed the magazine, and raced five blocks to Molly’s house. I arrived sweating and gasping heavily. “There’s an interview in…Carly…mentions us.”

Molly snatched the magazine and began to read aloud.

“‘At the Troubadour, it’s been great. There are these two girls who have really just made my evenings there.’”

“Can you believe it?” I yelled, loud enough for the neighbors to hear. The poodle next door began to yip.

“‘They’ve been sitting in the front row every night. They come to all the shows and they bake me bread, and they sing along.’”

“Amazing,” I screeched, then grabbed the magazine from Molly. I continued reading. “‘They know all the songs and, as many times as they’ve heard them, when I start them, they say, “Oh, great!” It’s really exciting to have such great…’”

I stopped midsentence.

“Such great what?” Molly barked.

I was devastated. Stunned into silence.

Molly grabbed the magazine from me and read. “‘It’s really exciting to have such great fans.’” She closed the magazine and looked at me. “What’s wrong?”

After a moment, I finally said, “

Fans

. She called us

fans

.”

“Oh.” Molly paused. “Well, she called us

great

fans. And she also said a lot of other cool things about us.”

“I thought we were friends.”

I left Molly’s house and trudged home. There I locked myself in my room, where I ate an entire still-frozen Sara Lee pound cake and listened to records—anyone but Carly. The words “such great fans” echoed through my head, replacing previous insults classmates had heaped upon me. “Fat ass.” “Lezzie.”

After four days I knew what I had to do. If Carly were truly my friend, she would understand why I had to write. I composed ten drafts of a letter before settling on the final version, which I then reread twenty times.

Dear Carly:

We saw your interview in

Where It’s At

and have to say, were very disappointed. We were surprised to be thrown into the category of “fans” with so many others who, I’m sure, you appreciate, but, well—we just thought we were more. We thought we were friends. I guess we were wrong. If we’re wrong about being wrong, please write back. We still think you’re a very talented woman.Hillary and Molly

I jumped on my bike, rode to the corner mailbox, and dropped in the letter before I could change my mind.