Quirkology (5 page)

Authors: Richard Wiseman

In 1962, the French caver and geologist Michel Siffre decided to track the movement of a glacier through an underground ice cave; to do so, he would have to live below ground for two months.

24

Rather than simply sit there taking measurements and twiddling his thumbs, Siffre made the most of his subterranean isolation by carrying out a unique experiment on the psychology of time. He decided not to take a clock with him into the cave, and so forced himself to rely entirely on his own body clock to decide when to fall asleep and when to be awake. His only link to the outside world was a telephone that provided a direct line to a team of researchers above ground. Siffre called the team whenever he went to sleep and woke up, and from time to time during his waking hours. Each time, the experimenters above ground did not give him any indication of the real time. Deprived of daylight for more than sixty days in his small nylon tent 375 feet below ground, Siffre’s ability to judge time became radically distorted. Toward the end of the experiment, he would telephone the surface, convinced that only an hour had gone by since his previous call—whereas in reality several hours had elapsed. When he emerged from the cave after two months, Siffre was convinced that the experiment had been terminated early, and that it was only in its thirty-fourth day. The experiment provided a striking illustration of how daylight helps our internal clocks to keep accurate time.

24

Rather than simply sit there taking measurements and twiddling his thumbs, Siffre made the most of his subterranean isolation by carrying out a unique experiment on the psychology of time. He decided not to take a clock with him into the cave, and so forced himself to rely entirely on his own body clock to decide when to fall asleep and when to be awake. His only link to the outside world was a telephone that provided a direct line to a team of researchers above ground. Siffre called the team whenever he went to sleep and woke up, and from time to time during his waking hours. Each time, the experimenters above ground did not give him any indication of the real time. Deprived of daylight for more than sixty days in his small nylon tent 375 feet below ground, Siffre’s ability to judge time became radically distorted. Toward the end of the experiment, he would telephone the surface, convinced that only an hour had gone by since his previous call—whereas in reality several hours had elapsed. When he emerged from the cave after two months, Siffre was convinced that the experiment had been terminated early, and that it was only in its thirty-fourth day. The experiment provided a striking illustration of how daylight helps our internal clocks to keep accurate time.

Other chronopsychological research has examined ways of minimizing the effects of perhaps the most common and annoying form of disruption faced by the modern-day body clock: jet lag. One of the more unusual and controversial studies in this area was carried out in the late 1990s by Scott Campbell and Patricia Murphy of Cornell University, and it involved shining lights on the back of people’s knees.

25

Previous work had shown that shining light into a person’s eyes fools the brain into speeding up or slowing down the subject’s biological clock, and so can help overcome the effects of jet lag. Campbell and Murphy wondered whether people might detect similar signals from other parts of their bodies. Since the back of the knee contains a large number of blood vessels very close to the surface of the skin, they decided to test their hypothesis by applying light to the region using specially designed halogen lamps. In a small-scale study, they found evidence that light applied to the back of the knee matched the biological clock-altering ability of light shone directly into the eyes.

25

Previous work had shown that shining light into a person’s eyes fools the brain into speeding up or slowing down the subject’s biological clock, and so can help overcome the effects of jet lag. Campbell and Murphy wondered whether people might detect similar signals from other parts of their bodies. Since the back of the knee contains a large number of blood vessels very close to the surface of the skin, they decided to test their hypothesis by applying light to the region using specially designed halogen lamps. In a small-scale study, they found evidence that light applied to the back of the knee matched the biological clock-altering ability of light shone directly into the eyes.

So what is the link between the ideas underpinning astrology and this fascinating scientific area of study? Not all chronopsychology is about spending months in caves and shining light on the backs of people’s knees. In another branch of this obscure discipline, scientists have examined the subtle influences that people’s birthdays may exert over the way in which they think and behave.

The concept behind this unusual branch of behavioral science is beautifully illustrated by the work of the Dutch psychologist Ad Dudink.

26

After analyzing the birthdays of approximately 3,000 English professional football players, Dudink found that twice as many were born between September and November as were born between June and August. It seemed that date of birth predicted people’s sporting success. Some may have viewed the result as compelling evidence for astrology, arguing that the planetary positions associated with Virgo, Libra, Scorpio, and Sagittarius play a key role in creating successful athletes. There is, however, a more interesting and down-to-earth explanation for Dudink’s curious finding.

26

After analyzing the birthdays of approximately 3,000 English professional football players, Dudink found that twice as many were born between September and November as were born between June and August. It seemed that date of birth predicted people’s sporting success. Some may have viewed the result as compelling evidence for astrology, arguing that the planetary positions associated with Virgo, Libra, Scorpio, and Sagittarius play a key role in creating successful athletes. There is, however, a more interesting and down-to-earth explanation for Dudink’s curious finding.

At the time of his analysis in the early 1990s, budding English footballers were eligible to play professionally only if they were at least seventeen years old when the season started, which was in August. Potential players born between September and November would therefore have been about ten months older, and more physically mature, than those born between June and August. These extra few months proved to be a real bonus when it came to the strength, endurance, and speed needed to play football, with the result that those born between September and November were more likely to be picked to play at a professional level.

Years of research have revealed an overwhelming amount of evidence for the effect in many sporting arenas. Regardless of when a sporting season starts, there is an excess of athletes whose month of birth falls in the first few months of that season. From American Major League baseball to British county cricket, Canadian ice hockey to Brazilian soccer, the month of birth of athletes is related to their sporting success.

27

27

Such chronopsychological effects are not limited to the lives of professional athletes; they also influence a factor that plays a key role in everyone’s life: luck.

Are you lucky or unlucky? Why do some people always seem to be in the right place at the right time, but others attract little but bad fortune? Can people change their luck? About ten years ago, I decided to answer these types of intriguing questions by conducting research into the psychology of luck. As a result, I have worked with about 1,000 exceptionally lucky and unlucky people drawn from all walks of life.

28

28

The differences between the lives of lucky and unlucky people are as consistent as they are remarkable. Lucky people seem to attract nothing but good fortune, fall on their feet, and appear to have an uncanny ability to live charmed lives. Unlucky people are the opposite. Their lives tend to be a catalog of failure and despair, and they are convinced that their misfortunes are not of their own making.

One of the unluckiest people in my study is Susan, a thirty-four-year-old nurse. Susan is exceptionally unlucky in love. She once arranged to meet a man on a blind date, but her potential beau broke both his legs in a motorcycle accident on the way to their meeting. Her next date walked into a glass door and broke his nose. A few years later, when she had found someone to marry, the church in which they intended to hold the wedding was burned down by arsonists just before the big day. Susan has also experienced an amazing catalog of accidents. In one especially bad run of luck, she reported having eight car accidents during one fifty-mile journey.

I wondered whether good and bad fortune really was chance, or whether psychology accounted for these dramatically different lives, and so I designed a series of studies to investigate. In one especially memorable study, I gave volunteers copies of a newspaper and asked them to tell me how many photographs were inside. What I didn’t tell them was that halfway through the newspaper I had placed an unexpected opportunity. This “opportunity” took up half the page and announced, in huge type, “Win £100 by Telling the Experimenter You Have Seen This.” The unlucky people tended to be so focused on the counting of the photographs that they failed to notice the opportunity. In contrast, the lucky people were more relaxed, saw the bigger picture, and so spotted a chance to win £100. It was a simple demonstration of how lucky people can create their good fortune by making the most of an unexpected opportunity.

The results revealed that the volunteers were making much of their good and bad luck by the way they were thinking and behaving. The lucky people were optimistic, energetic, and open to new opportunities and experiences. In contrast, the unlucky people were more withdrawn, clumsy, anxious about life, and unwilling to make the most of the opportunities that came their way.

Some of my most recent work in the area has taken a chronopsychological turn and explores whether there is any truth to the old adage that some people are born lucky.

29

The project had its roots in a curious e-mail that I received in 2004 from Jayanti Chotai, a researcher at the University Hospital in Umeå, Sweden.

29

The project had its roots in a curious e-mail that I received in 2004 from Jayanti Chotai, a researcher at the University Hospital in Umeå, Sweden.

Much of Jayanti’s work examines the relationship between date of birth and various aspects of psychological and physical well-being. In one of his studies, Jayanti had asked a group of about 2,000 people to complete a questionnaire measuring the degree to which they described themselves as sensation seekers, and then looked to see whether there was a relationship between their questionnaire scores and their birth months.

30

Novelty and sensation seeking are fundamental aspects of our personalities. Very high sensation seekers can’t stand watching movies that they have seen before, enjoy being around unpredictable people, and are attracted to dangerous sports such as mountain climbing or bungee-rope jumping. In contrast, very low sensation seekers like to see the same movies again and again, enjoy the comfortable familiarity of old friends, and don’t like visiting places that they haven’t been to before. Jayanti’s results suggested that sensation seekers tended to be born in the summer, but those more comfortable with the familiar were likely to be born in the winter. Jayanti’s e-mail explained that he had read about my work on the link between personality and luck and he wondered whether some people really were born lucky. It was an intriguing idea, and the two of us decided to team up and discover whether there was any truth to the expression.

30

Novelty and sensation seeking are fundamental aspects of our personalities. Very high sensation seekers can’t stand watching movies that they have seen before, enjoy being around unpredictable people, and are attracted to dangerous sports such as mountain climbing or bungee-rope jumping. In contrast, very low sensation seekers like to see the same movies again and again, enjoy the comfortable familiarity of old friends, and don’t like visiting places that they haven’t been to before. Jayanti’s results suggested that sensation seekers tended to be born in the summer, but those more comfortable with the familiar were likely to be born in the winter. Jayanti’s e-mail explained that he had read about my work on the link between personality and luck and he wondered whether some people really were born lucky. It was an intriguing idea, and the two of us decided to team up and discover whether there was any truth to the expression.

Jayanti’s previous work had suggested that the relationship between birth month and personality was real, but small. To detect very small effects, we knew we needed to design an experiment involving thousands of people. We also knew that proposition wasn’t going to be easy. Getting even a few hundred students to participate in research is often problematic, and we needed thousands of people from all walks of life to take part if we were to have any chance of finding what we were looking for. Luckily, help was at hand.

The Edinburgh International Science Festival in Scotland is one of the oldest science festivals in the world, and the largest in Europe. By making the experiment part of the festival, we would stand a good chance of attracting the large numbers of people we needed. The festival organizers gave us the green light, and we set up a simple Web site where people could enter their birth dates and then answer a standard questionnaire that I had devised to assess their levels of luck.

Carrying out large-scale public experiments is always an unpredictable affair. Unlike laboratory research, you have only one opportunity to get it right, and you never know whether people will give up their time to participate. However, our study attracted the public’s imagination and quickly spread around the globe. Within hours of going live, we had hundreds of people using the site. By the end of the festival, we had collected data from more than 40,000 people.

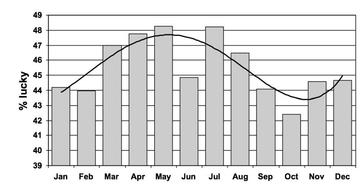

The results were remarkable. Jayanti had found that those with summer births were the risk takers. Our results revealed that those born in the summer (March to August) also rated themselves as luckier than those born in the winter (September to February). The resulting levels of luckiness across the twelve months showed an undulating pattern that peaked in May and was at its lowest in October (see graph 1). Only June failed to fit the pattern—something that we put down to a statistical blip.

Graph 1 Born Lucky Results: The Percentage of Lucky

People Born in Each Month of the Year.

People Born in Each Month of the Year.

There are lots of possible explanations for an effect such as this. Many revolve around the notion that the ambient temperature is lower in winter than in summer. Perhaps because babies born in winter enter a harsher environment than those born in the summer, they remain closer to their caregivers and so are less adventurous and lucky in life. Or perhaps women who give birth in late winter have had access to different foods than those who give birth in the summer, and this affects the personality of their offspring. Whatever the explanation, the effect is theoretically fascinating, and it suggests that the temperature around the time of birth has a long-term effect on the development of personality.

But before accepting any of the temperature-related explanations, it is important to rule out other possible mechanisms. Maybe the effect has nothing to do with temperature, but instead concerns some other factor that varies during the year. Proponents of astrology might argue that heavenly activity affects personality and that the alignment of the planets and stars during the summer months somehow gives rise to a luckier life.

The only way of assessing the competing explanations would be to repeat the study in a place where there is a different relationship between temperature and the months of the year. If the temperature-related explanations were correct, then the warmer months should still be associated with lucky births. If the astrological explanations were right, then May, June, July, and so forth should emerge as the lucky months.

Other books

Lace & Lassos by Cheyenne McCray

Gengis Kan, el soberano del cielo by Pamela Sargent

34 Pieces of You by Carmen Rodrigues

Memory Scents by Gayle Eileen Curtis

Bare Bones by Kathy Reichs

Kickass Anthology by Keira Andrews, Jade Crystal, Nancy Hartmann, Tali Spencer, Jackie Keswick, JP Kenwood, A.L. Boyd, Mia Kerick, Brandon Witt, Sophie Bonaste

Jane Feather - [V Series] by Virtue

A Vulnerable Broken Mind by Gaetano Brown

Chevon's Mate by April Zyon

Alone in the Ashes by William W. Johnstone