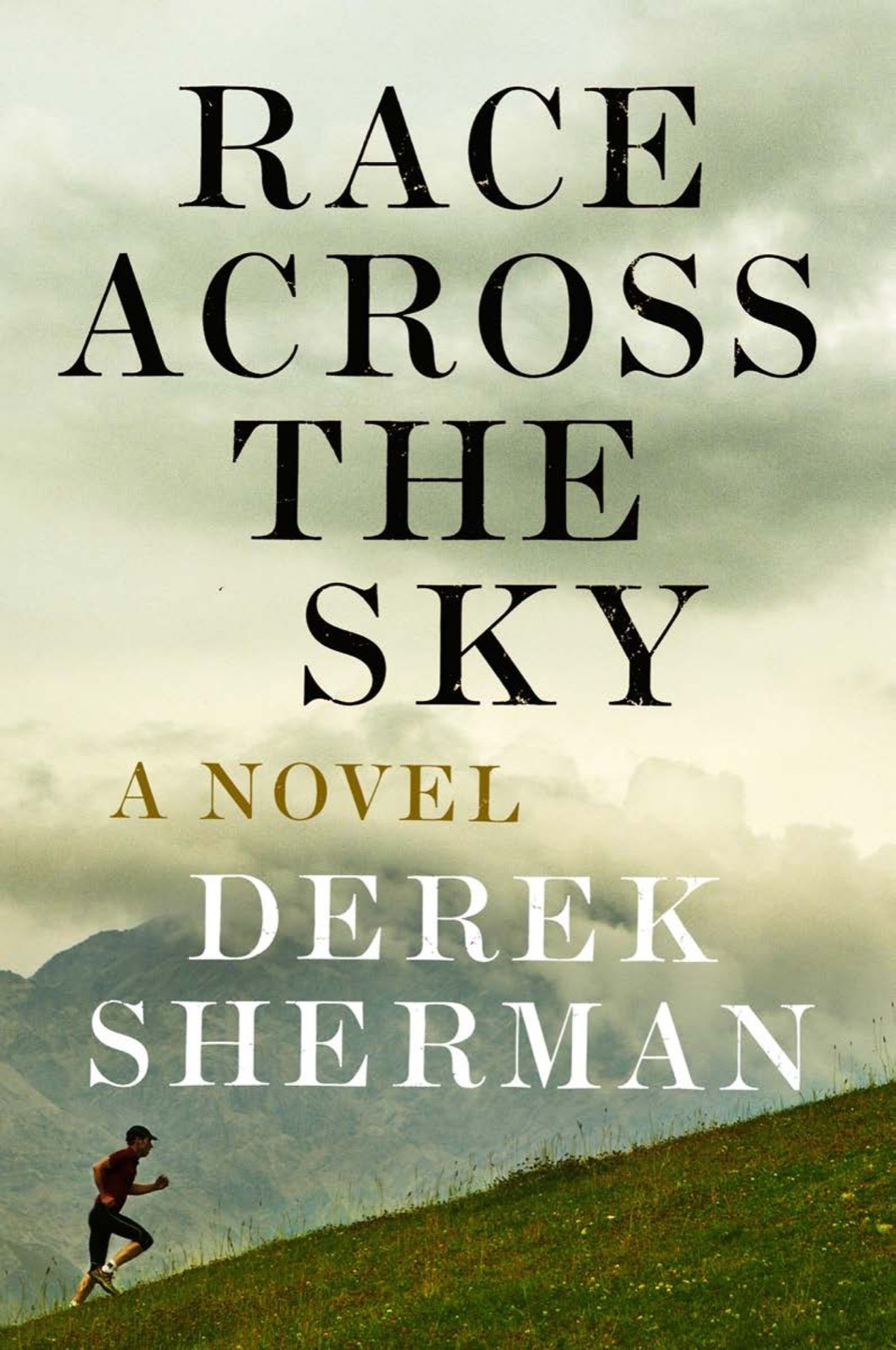

Race Across the Sky

Read Race Across the Sky Online

Authors: Derek Sherman

RACE ACROSS THE SKY

KERRI SHERMAN

DEREK SHERMAN

works in advertising as a writer and Creative Director. His work has received every major industry award, and been named among the best of the last twenty-five years by

Archive Magazine

. He is a cofounder of the Chicago Awesome Foundation, a charity dedicated to awarding micro-grants. He lives in Chicago with his wife and children. This is his first novel.

A

NOVEL

Derek Sherman

A PLUME BOOK

A PLUME BOOK

PLUME

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com

First published by Plume, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 2013

REGISTERED TRADEMARKâMARCA REGISTRADA

REGISTERED TRADEMARKâMARCA REGISTRADA

Copyright © Derek Sherman, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this product may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author's rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Sherman, Derek.

Race across the sky : a novel / Derek Sherman.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-101-59860-3

1. BrothersâFiction. 2. Marathon runningâFiction. 3. BiotechnologyâExperimentsâFiction. I. Title.

PS3619.H4647R33 2013

813'.6âdc23 2012045790

PUBLISHER'S NOTE

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

For Noah and Sage. You are the inspiration for this book. Each of you appeared and brought a part of this story with you.

Thank you both very much

.

If we don't play God, who will?

âJames Watson, after discovering DNA

Hymns for the Earth

â¢Â â¢Â â¢Â â¢Â â¢Â â¢Â â¢Â â¢Â â¢Â â¢Â â¢Â â¢Â

T

hey ran together across the trails toward Twin Lakes, so close on the narrow path that their slick shoulders touched.

June stayed just beside him, thin, tiny, her straw-colored hair tied back, her blue shirtsleeves rolled up, her arms damp. The feel of her skin kept him awake, alert, possibly even alive. Fourteen hours ago, Caleb Oberest had started running these trails outside Leadville, Colorado, at four in the morning. He still had not stopped.

The Leadville 100 ultramarathon course had taken him fifty miles along alternating patches of sage and gold forest, over open chestnut earth, and up twelve thousand feet of narrow, tawny trails skitting between the bluestem and switchgrass. He had run over Hope Pass into the small mountain town of Winfield, and now he was making his way back.

Two hundred other runners were scattered along the course behind him. Just a few hours earlier, there had been three times as many; Caleb knew they would thin down to half that before long. He was sixty-seven miles into the race, the point where bodies began to break apart, when runners collapsed along the trails, when the goal shifted from distance and time, to survival.

Caleb's tall forty-three-year-old body and narrow face had long since been depleted of all fat. His thinning brown hair dangled just below his ears. When he ran, a straight line could be traced from the top of his head to the balls of his feet. His arms pumped as pistons. His long, reedy legs leapt over roots and rocks. Only his eyes moved freely, drifting upward, sweeping the ground in front of him for stones and tree roots. They focused on nothing. Circles. Blurs.

Mack had instructed him to finish in the top ten. To accomplish this, Caleb would need to reach the finish banner in the old mining town of Leadville in under nineteen hours. Last year he had finished in twenty, placing thirteenth. The year before that, he had collapsed in agony on the eighty-first mile, two of his abdominal muscles torn and a small bone in his heel broken. But none of that mattered now. The outcome, Caleb knew, had nothing to do with the past, or the banking crisis, or the value of the dollar. It was dependent only on his own focus and desire. They called it the Race Across the Sky, but Caleb understood it was just the opposite, a race into himself.

The course markers led diagonally down the mountain along a trail filled with different sized stones. Caleb's left leg was a good eight inches above his right. It would be simple to tear a knee, or fracture a hip. In the distance the sky seemed to signal the end of day.

Beside him he felt June, heard her breathing, and her soft encouragements. Of course she didn't need to speak. Having her there was enough.

June was nowhere near as strong a runner. She was solid for seventy miles give or take, but after that her body broke down quickly. She had volunteered to pace him these last thirty miles. Caleb had not approved; it raised too bright a flag. Mack did not allow romantic relationships of any kind in the Happy Trails Running Club. They were, he taught, defocusing. During Caleb's ten years in the Happy Trails house, he had seen Mack expel many members who breached this protocol. And he had agreed completely.

Caleb had come to Happy Trails seeking pure isolation, focus on himself, and forward motion, and for eleven years he had lived in this exact state. He had never been afraid of mudslides, bears on the trails, having to make it nine more miles with a fractured ankle, or suffering weeks of pneumonia without antibiotics, even though all of these things had happened to him. But now he felt a desperate fear of losing something he could not bear to.

During these two months since June had moved in, Caleb had found himself watching for her in the house, in town, on the trails during their daily eight-hour run; it seemed to be out of his control. For a month now, he had been meeting her secretly in the fields around the mountains, and there they would consume each other with a veracity which overwhelmed him. If Mack had understood just how deep they had already gone, he would have enacted drastic measures. He would expel June from the house. And Caleb was no longer sure that he could continue without her. The thought of breathing this same air without her weakened him more than any seventy-degree ascent. The burn of his feelings had to be pushed deep inside, where they would be invisible to anyone else. And so to move now with June through these darkening trails was a bliss that overwhelmed the agonies ripping through his bones and lungs.

The two of them ran down into Twin Lakes. A few townspeople stood there watching, some clapping for them, and then the paved street led back into the wilderness. A copse of branches extended over the path ahead like witches' fingers, trying to pull them into the woods. Caleb raised his free hand over his eyes and broke through into an open field, which spread to the granite peaks of La Plata and Elbert ahead. He pulled away from June and ran free under the vast sky, lost in the raw energy of the world.

The physics of running one hundred miles was simple: for the first thirty miles, his body burned protein and glycogen. The protein he could restore with food at the aid stations that appeared every seven miles. Glycogen was another matter. When the body exhausts the liver's store, it assumes that whatever it is running from has either gone away or is about to kill it, and stops production. If pushed forward beyond this point, the body begins digesting itself. This had begun happening to Caleb seven hours ago.

His feet had swollen a half size; they pushed against the thin fabric of his running shoes. A tight knot of compressed heat had begun burning in the ball of his left foot. Ahead the sun dipped behind a distant peak, like a lamp being shut off, and the bruise-colored sky lowered behind the mountains. Caleb tensed. Nights were his weakness. He suffered hallucinations. Strange deliriums would descend; anything might happen.

The course turned toward a creek. By its bank he rec- ognized Lynette Clemons, a music teacher who had been last year's women's champion.

“Nice job,” she smiled. “Awesome day.”

But Caleb did not speak during runs. For him, talking ruined the inner exploration that he had thought everyone did this for: the digging to the bottom, the scraping of the deepest nerves. Instead, he plunged into the creek. The cold pierced his body to his waist, took away his breath. He felt June's fingers brush his, slip away, and finally grasp his hand, a nearly symphonic energy flow between them, his depleted body recharging.

“Slow down,” she told him. So he did.

They were nearing the next aid station. Inside these tents were coolers of food and drink, and a cluster of spouses, friends, and children of competitors, waiting nervously for their loved ones to limp inside like refugees. Caleb had no relatives here, but he had something demonstrably better: the Happy Trails Running Club.

Sixteen people who were his housemates, his partners, his team. Half of them were scattered somewhere behind him, running through the Rockies. Mack had installed the other six as pacers, waiting to run beside their housemates for twenty miles, and sacrifice their own opportunity to finish Leadville to urge them on.

On the far bank a blue tent fluttered silently. He glanced at June as he emerged from the creek, to be certain she was all right. As he did, his left foot scraped a jagged stone, and the hot ball inside it broke open. Caleb gasped. Everything spun madly. As he doubled over on the rocky ground, he felt June touch his back.

She slipped her thin arm under his shoulder and tried to pull him toward the aid station. It did not seem like a workable solution. His body began to feel shockingly tired.

“Look,” June pointed encouragingly.

Distantly he saw Rae and Kyle running out toward them from the tent. Rae was dark-skinned and stocky, her straight black hair pulled back in a tight and ever-present ponytail. She might have been of Pamlico or Sicilian descent, but Caleb had learned that her parents were prominent members of a western Long Island synagogue. She had been living in the Happy Trails house for two years when he had arrived.

June took a self-conscious step away and let Rae help him into the tent, where a twenty-eight-year-old former methamphetamine addict named Kyle stood with a kit bag. Caleb sat on the cold ground, shivering as he watched Kyle pull off his left shoe, roll his white sock down his ankle, and unwrap his Elastikon tape. Caleb chanced a look at his bare foot. His toes were permanently swollen into unrecognizable shapes, the nails black and violent. On the ball he saw a blister the size of an egg pulsing with his heartbeat.

Kyle held a razor blade between his fingers. With a grimace, he sliced the blister and pushed its sides together. Caleb cried out, his eyes rolled up to the dark sky. The stars there spun, he saw, like circus toys, pulling him into their glittering orbit, then dropping him with disregard back to the cold ground.

Kyle rubbed benzoin over the wound, wrapped his foot in fresh tape, and shook baby powder around the edges. He pushed new shoes, a half size larger, onto his feet and helped him stand.

Caleb pulled deep breaths as strands of wet brown hair fell across his eyes. Rae handed him a cup of chicken broth, and the salt absorbed into his starving cells; the small pieces of soft carrot were gone before his tongue could taste them.

“Twenty-five more,” Rae told him.

Twenty-five miles seemed impossible. An essential rhythm had been broken, was gone and could not be recaptured.

Rae turned to June. “I can pace him from here.”

“I'm with him,” June replied.

He hoped Rae had not caught the underlying meaning.

“Yeah? You feel good?”

“She's warm,” Kyle agreed. “We can wait for Juan and Leigh. They'll both need a pace.”

He leaned in and strapped a Petzl headlamp around Caleb's skull. Caleb felt its band snap tightly around his hair.

“You're awesome,” Kyle nodded.

Rae looked at June. “Keep him slow, okay?”

Hobbling out of the tent, Caleb took in the situation. The neon course markers pointed a path toward Halfmoon, a steep ascent he knew well from previous years. He attempted a very slow jog. It was not too bad; June was next to him, whispering affirmations as they moved upward. Just then the sky gave up, and he was propelled into absolute darkness.

The circle of bright yellow light from the Petzl was all he could see. Even with June there, Caleb felt an isolation so immense he could not grasp it. His other senses heightened, he heard the air echoing through his lungs, animals scurrying, a metallic taste ran over his tongue. He pushed into a light run, but the course seemed against him now. At some point the orange course markers lifted off the ground and floated in the air, leaving tracers behind them. His teeth chattered violently in the mountain wind. Once he had chipped a bottom tooth on a night like this.

“Slow it down,” June called from behind him.

But he couldn't. There was no way to get through the night but to try, ridiculously, to outrun it.

Some miles later the dirt trail under his feet became paved road. His bones took this poorly. The road had been closed to cars, but in the darkness the headlamps of the runners behind him appeared like headlights. He slowed to a fast walk, and June ran her hand along his thin shoulders.

“Smile with the sky,” she whispered.

Caleb forced a smile onto his face. This was one of Mack's infamous techniques. Other runners joked uneasily about the Happy Trails Smile, but it created oxyendorphins, which helped push pain aside. Amazing, Caleb thought, how kinetic energy works in the world.

They approached the Fish Hatchery aid station. Under the fluttering nylon they slammed Powerade and some thick orange puree. A surprisingly large crowd had gathered here in the pitch of night, cheering anyone who made it by. He heard runners who had dropped out exchanging stories of what had broken them. What was it about night, he wondered, that compelled people to talk so much? He had prepared for agony; he had prepared for blisters and night terrors; he just had not prepared for so much jabbering.

Outside, the paved road returned again to dirt, signaling the climb up Sugarloaf. As he began to ascend inside his circle of yellow light, he remembered what he had done.

He had sent the letter.

It had been hidden beneath his mattress for a week. At night, Caleb could feel the energy seeping up through the fibers of his futon. Just having written it, he understood, had altered him somewhat, rearranged the chemicals of his cells.

Before the start, during the distraction of the weigh-in, the crowd, and the darkness of three in the morning, Caleb had slipped briefly away, pulled the letter from his waistband, and dropped it casually into a Leadville mailbox.

Now he shivered. What events had he just set in motion? After eleven years of silence, how would Shane react? How much at risk had he just put himself of losing everything?

The idea of this blue envelope journeying to his brother carried him up the incline. He passed a runner who was clearly sleeping as he shuffled up the path. At Hagerman Pass, he felt strong and believed he could finish the final fifteen miles without walking. They passed the next aid station, but he kept running. Even though he knew June would stop to rest, he could not risk stopping. That was past him now.

In the dark the course corkscrewed downward; a vertiginous spiral appeared before him. He focused on his legs, one foot, then the other. He found the void. It seemed to be going well.

But at the turn of the trail, somewhere near ninety miles in, Caleb's legs suddenly convulsed, and before he understood what was happening he had stopped, pushing his hands into his swollen quads, willing the blood to reverse out of them, tears rolling from his eyes. He opened his mouth and began to vomit.

A tall runner caught up to him then, panting, slid around him, and continued down the course. How many more were ahead of him? Less than ten? Had he failed his promise to Mack? Time passed, he had no concept of how much. He stepped off the trail to urinate. What came out was brown and thick.