Radio Free Boston (2 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

WBCN

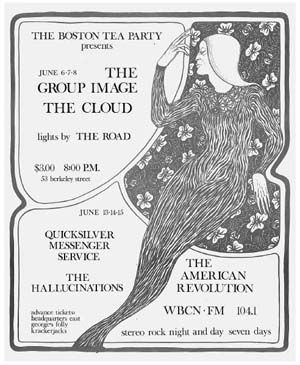

presents concerts at the Boston Tea Party, June 1968, original poster. Courtesy of the David Bieber Archives. Photo by Matt Dolloff.

Don Law, who would eventually replace Steve Nelson as general manager

of the Tea Party and go on to become Boston's most successful rock impresario, met Ray Riepen at Boston University (

BU

) where he was a student, as well as an instructor who conducted an educational workshop entitled “Evolution of the Blues.” Law's early music education came from his quite famous father, Don Sr., who worked as a talent scout and producer for Brunswick and then Columbia Records, plying the American South for talent, which included the iconic Robert Johnson, Memphis Minnie, and even Gene Autry. Through his father, Don Jr. had developed some hefty connections on his own. He brought in blues artists to play and speak at his

BU

workshops, including the already-legendary Muddy Waters and his outstanding piano player Otis Spann. “[The workshop] got a lot of attention; the

New York Times

covered it,” Law mentioned, “and that's how I met Riepen. At the time, he was struggling with the Tea Party; it was sort of hit or miss.” The pair shared their backgrounds, and Law filled Riepen in on his recent successes as a young player in the music business. “I considered myself somewhat of an authority because I had worked as a college [booking] agent and had gotten Barry and the Remains their recording contract with Epic.” Not only that, Law had also helped the Boston band land a spot on the road as an opening act for the Beatles. Riepen was impressed, quickly inducting Don Law into the Tea Party's inner circle. “It's been written that I was a lot smarter than I think I was,” Law revealed, “or more Machiavellian. But the truth is that we were just kids who wanted to be in the music business. There wasn't any money in live entertainment anyway; it was all sort of a small business; we were doing it because we thought it was fun. Here it was: 1967 and '68, we really didn't have that much pressure; we were [just] having a blast. [But] then, the Earth moved!”

In the Tea Party's daily business conundrum, accounts receivable often didn't cover accounts payable, but the inner circle let it ride, counting on the next night's gate receipts to save the day. However, even as 1968 arrived with more consistent bookings, the profits were never outstanding. Plus, as Don Law remembered, his boss could be a financial problem himself: “Every time I'd get myself in a good position and start making money, [because] you had to have some around to make guarantees [with bands and their agents] and pay out bills, [Riepen] would just come in and take it all out to fund whatever else he was doing. I was always going, âOh no! I'm down to zero again!' I was always playing this game trying to keep the place afloat, [acting] as if I had resources . . . and I didn't!” Riepen's personal

life also bordered on the dramatic, as Law recalled with a smile: “He was a really sweet guy, but he was just so difficult. I'd get a call at three in the morning . . . it was him: âI'm over here in Belmont and I'm in jail and I don't have a license. Can you get me out of here?' He didn't have a license, and he would always drive without one. He had a Porsche one time and he was visiting some girlfriend on the Hill, then someone stole his Porsche. He said, âAw, fuck it,' went down the Hill and just bought himself a Volkswagen!”

Ray Riepen asserted that he didn't make any money off the Tea Party, but that's only true depending on how you do the math. To his credit, he kept the ticket prices low, insanely cheap by today's standards, and the hippies who were around then will always tell fond memories about how they saw Led Zeppelin or The Who for less than five bucks. Even so, Riepen did make money off the club, but he just spent it as quickly as he made it. Some of those expenditures, like financing his impending venture at

WBCN

and eventual stake in the

Cambridge Phoenix

newspaper, were clever and considered business endeavors. Others were more impulsive, as Don Law explained: “By 1969, 1970, there was this âFree the Music' thing [in which] people thought there shouldn't be any charges for music. There was a lot of this, so we always tried to be sensitive about it and keep the prices down. Riepen took it upon himself to buy a Mercedes 600 limo! It was as ugly and corporate as you could get: a long black box that the only other people in the world used was the Secretary-General of the U.S. or the Pope. He'd pull up in this massive limousine at the Tea Party; I'd be out there trying to run things, and people are shouting, âFree the music! Free the music!' He'd get out in his three-piece suit and stand there on the curb. I'd just go: âDamnit!' And you know, if you looked in that limo, you'd notice that it was stacked with books. He would spend half his life in this thing in the back seat; it was really his apartment of sorts.”

As a well-read intellectual, Ray Riepen noticed some recent developments in radio on the West Coast. In San Francisco, “underground radio” had made its debut on the

FM

band with a reasonable level of success. The idea began percolating in his head that the same could be accomplished in a place like Boston, with its profusion of freethinkers at the area's multitude of colleges and universities. “There were 84,000 students here and they were all starting to smoke dope,” Riepen asserted. “They were obviously hipper than the assholes running broadcasting in America.” He knew that a significant audience was hearing the music they desired every night at the

Tea Party, but they were not hearing that music on the radio. Up to that point, Boston was ruled by the format that had been dominant in America for over a decade: Top 40, with its tight playlist and hyperactive teams of shouting

DJS

to introduce the songs. The recipe of this winning formula was based on repetition. Since listeners remained locked on a radio station for discrete periods in the day based on their own personal schedules and preferences, it was important that while tuned in, those listeners heard the songs they absolutely loved. Relentlessly rotated on the air, that list of “40” selections ensured that the most popular songs would be heard by the highest-sized audience possible. A station programmed successfully in this manner could generate huge numbers of listeners throughout semiannual ratings periods and, as a result, demonstrate to potential clients that it was the one to purchase advertising on, then command top dollar for every commercial sold.

The Boston Tea Party schedule, May/June 1969. Courtesy of the David Bieber Archives. Photo of schedule by Matt Dolloff.

Top 40 radio stations in the sixties weren't just marked by their choice of music; there was also a style or aesthetic behind the sounds of those frequencies. Program directors encouraged their

DJS

to shout with abandon into the microphone, modulate their voices up and down in exaggerated or phony exuberance, and deliver high-powered raps with machine-gun

velocity. Most of what an announcer needed to say in a break between two songs could be accomplished by talking over the fading music of the first and the instrumental introduction to the second, before the singer's voice kicked in. Radio station engineers wired up echo devices so that

DJS

could project their voices with the booming, amplified voice of God (or at least Charlton Heston as Moses). Inane collections of sound effects, bursts of fast-paced phrases, and clips of words snipped from comedy records were produced into short station

IDS

(call letters plus city of origin) to link up songs and constantly remind listeners what radio station they were listening to.

DJS

had their own theme music, jingles, and personalized breakers to instantly convey their identity to the audience. “Cousin Brucie” (Bruce Morrow) at

WABC

in New York City assembled a brief, instantly recognizable montage of voices yelling out his name, while closer to home at Boston's

WMEX-AM

, celebrated announcer Arnie “Woo-Woo” Ginsburg earned his nickname by punctuating on-air raps with blasts from a train whistle.

As Lulu's “To Sir With Love,” “The Letter” by the Boxtops, “Windy” from the Association, Bobby Gentry's spooky “Ode to Billie Joe,” and “Groovin'” from the Rascals became the biggest

AM

radio hits of 1967, immense changes were afoot in the youth culture and, eventually, in the media that served it. Just as the Beatles had quickly outgrown playing neat two-and-a-half-minute pop masterpieces by absorbing fresh influences and exploring new adventures, fans began searching for more as well. Young, unsullied minds lay open to innovative approaches in art, music, spirituality, lifestyle, health, sex, and politics. The sixties became the stage upon which these great changes occurred, revolutions approaching and flying by like road signs on a highway. The specter of the Vietnam War haunted the country, uniting America's teenagers and propelling them forward with urgency. Why would an eighteen-year-old seeker wait to experience an

LSD

trip or pass up a weekend retreat with some Indian guru, when he knew that the following week he might be plucked by his draft board and sent off to dodge shrapnel in Da Nang. This great injustice, visited upon the youth by political leaders seemingly ensconced on Mount Olympus, was an accelerant poured on the fire of the times.

Encyclopedia Britannica

summarized this turbulent time in American history: “The 1960s were marked by the greatest changes in morals and manners since the 1920s. Young people, college students in particular, rebelled against what they viewed as the repressed, conformist society of their

parents. A âcounterculture' sprang up that legitimized radical standards of taste and behavior in the arts as well as in life.” A potent antiwar movement poured out of the American campuses and took to the streets. Swiftly rising opposition to the U.S. Air Force bombing of North Vietnam brought a hundred thousand demonstrators into New York City in April 1967, and an October march on the Pentagon drew almost the same number. The black population, still largely unable to claim the rights won during the Civil War a hundred years earlier and guaranteed under the Constitution, had waited long enough. Simmering anger boiled over into violent action, as evidenced by race riots in dozens of American cities, particularly Watts in L.A. and other revolts in Newark and Detroit. In the latter, rampant looting and one thousand fires destroyed almost seven hundred buildings in less than a week. The nonviolent civil rights movement, led by Martin Luther King Jr., encountered stiff resistance at every turn but steadily grew, its ranks swelled by sympathetic supporters in the antiwar movement. Many young protestors also rejected the capitalist stance of their parents, instead taking it one day at a time to explore alternative lifestyles. The recreational use of marijuana and

LSD

soared while drug-culture gurus like Timothy Leary urged his followers to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.”

It's no mystery, then, that music and the radio stations that played it were due for a rocket ride of their own. History points a big finger at the Beatles' June 1967 release of

Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

as the flash point. There were others, and some came before, but the Beatles had the attention of the world as pop music's number 1 spokesmen, so the group's latest work was greeted with far more attention than any other. Paul Evans, writing in the

Rolling Stone Album Guide

, lauded

Sgt. Pepper's

as no less than “the most astonishing single record of popular music ever released.” Never before had a band with this magnitude made such a bold artistic statement, shrugging off its monochrome past and embracing a fresh Technicolor one. The group realized this, evidenced by the cover photo featuring the waxen Fab Four replicas in charcoal-grey suits standing solemnly at their own funeral, in front of the “new” John, Paul, George, and Ringo in colorful marching-band outfits. The Beatles didn't necessarily need the promotion of a hit song, so the band chose not to release any singles from

Sgt. Pepper's

, instead presenting the twelve-inch vinyl record as a whole piece not unlike a complete classical work of old. Top 40

DJS

who didn't want to be left out of the newest Beatles project blew

the dust off their turntable speed levers and moved them (maybe for the first time) from 45 rpm down to 33, and then started playing songs of the album.

Sgt. Pepper's

became the largest-selling album in America from July into October 1967, ushering in an era of sophistication in popular music that hadn't existed much before. Now, many listeners began grooving to complete albums rather than stacking up a pile of three-minute singles on their record player.