Rampage

Authors: Lee Mellor

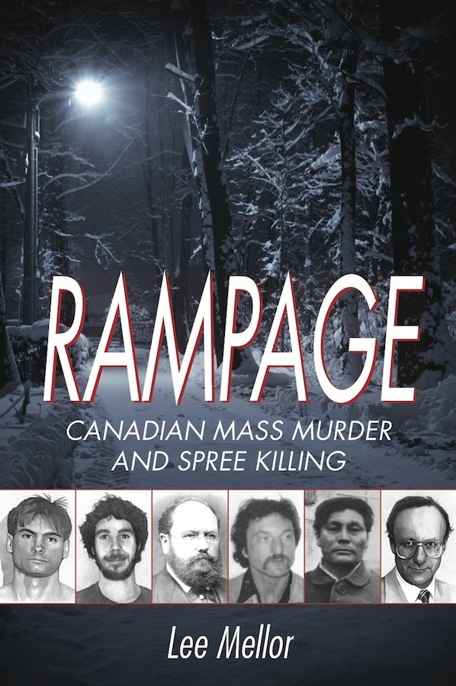

RAMPAGE

Canadian Mass Murder

and Spree Killing

Lee Mellor

This one is for the Brambergers:

Deborah, Peter, Raymond, and Liesa, who have always been there for me

Contents

- Foreword by Robert J. Hoshowsky

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part A: Defining Mass Murder and Spree Killing

- 1. Two Kinds of Rampage Murderers

Marc Lépine

... The Polytechnique Gunman

Peter John Peters

... Tattoo Man - 2. The Problem with Boxes

Swift Runner

... The Cree Cannibal

Rosaire Bilodeau

Robert Poulin

... St. Pius X School Shooter

David Shearing

... The Wells Gray Gunman - 3. The First Rampage Killers in Canadian History

Thomas Easby

Henry Sovereign

Patrick Slavin

Alexander Keith Jr.

... The Dynamite Fiend - Part B: Personality Disorders

- 4. Narcissists, Anti-Social Personalities, and Psychopaths

Valery Fabrikant

Robert Raymond Cook

James Roszko - Part C: Spree Killers

- 5. The Utilitarian

Gregory McMaster

Jesse Imeson - 6. The Exterminator

Marcello Palma

... The Victoria Day Shooter

Stephen Marshall - 7. The Signature Killer

Dale Merle Nelson

Jonathan Yeo

... Mr. Dirt - Part D: Mass Murderers

- 8. The Family Annihilator

Leonard Hogue - 9. The Disciple and the Ideological Killer

Joel Egger

... Order of the Solar Temple

Joseph Di Mambro and Luc Jouret

... Order of the Solar Temple - 10. The Disgruntled Employee

Pierre Lebrun

... The OC Transpo Shooter - 11. The Disgruntled Citizen

Denis Lortie - 12. The Set and Run Killer

Albert Guay

Louis Chiasson - 13. The Psychotic

Victor Hoffman

... The Shell Lake Murderer - Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

Foreword

Robert J. Hoshowsky

Memory is a peculiar thing. While most of us cannot remember specific details about uneventful activities like our Monday-to-Friday drive to work or school or what we ate for lunch from one day to another, the opposite holds true in times of tragedy. Unable to recall the trivialities of everyday life, we know precisely where we were the moment our nightmares became reality. When a loved one dies, we readily remember the time of day, sights and smells, and who we were with when we received the news. Like new earth created in time when leaves fall and plants decay, these memories mercifully remain buried, until something happens to reanimate them in monstrous detail.

When I heard from fellow true crime author Lee Mellor about his latest project — a book about spree killers and mass murderers — I immediately thought of an old friend who had suffered loss on such a scale as to be unimaginable: a murder-suicide that saw five members of his family dead in just minutes. In the initial confusion and shock, the awful details did not make themselves known right away, but unfolded over several horrifying hours.

Back in late March of 1985, I was at the Glendon Campus of York University in Toronto. Unlike the formidable Keele Street campus, the Glendon Campus in the city’s north end has an almost village-like feel to it, a mixture of noncommittal sixties-style beige structures alongside gorgeous historic buildings crafted from brick and stone, surrounded by old trees and footpaths. At the gym sign-in desk, I met someone I hadn’t seen since grade school. We spoke for a few minutes, while in the background breaking news came over the radio about a shooting in the city’s west end. I didn’t pay a great deal more attention until after my workout, when I passed the desk and heard another news announcement, this time stating that more than one person had been shot and killed on Quebec Avenue.

I know someone who lives on Quebec Avenue

, I thought.

Could it be Marko?

The thought bothered me as I walked back to my parents’ home, where my mother immediately said, “Did you hear about the murders in the west end? Doesn’t your friend Marko live on Quebec Avenue?” I started to feel something was terribly, irreparably wrong.

She was referring to Marko Bojcun, the editor of an English-language Ukrainian newspaper called

New Perspectives

. Just twenty at the time, I had been contributing to the paper for several years, writing articles and taking photos mainly of community and political events. Marko was not only a mentor to me when I started submitting pen-and-ink drawings to the publication while in my teens, but a gentle, highly intelligent, kind-hearted, and patient man who tolerated my youthful enthusiasm and utter lack of experience with sound advice and a ready smile. I immediately called the west-end apartment he shared with his wife. A gruff-sounding man answered the phone during the first ring. I asked to speak with Marko. The man on the other end identified himself as a Toronto Police detective, and asked who I was. “A friend,” I responded, feeling as though hands were around my throat, choking me. In the background, I heard male voices muttering, “Oh, Jesus,” and, “Goddamn it!” After a moment, I croaked, “Can I speak to Marko?” My request was followed by a very long pause, after which the detective softly replied, “No … not now,” and hung up. It was at that moment I knew something tragic had happened, and ran to the living room to turn on the television.

We watched as station after station put together details from neighbours and police about what happened: a man who had come to Canada from the United States had shot and killed four relatives before turning the weapon on himself. That man was Marko’s brother-in-law, and the family members were the killer’s parents, an uncle, and his sister — Marko’s wife, Marta.

Minute by minute, other facts emerged. Marko’s brother-in-law was Wolodymyr Danylewycz, a thirty-three-year-old from Cincinnati, Ohio. A disturbed soul, he came to Toronto for a visit with other family members, bringing along with him a hidden handgun. On that sunny Sunday, March 24, the family was gathered in the triplex apartment, when Danylewycz asked Marko to get ice cream from the local store. Soon after he left, a loud discussion erupted, and shots were fired around 3:00 p.m. Neighbours called police. Returning to the apartment, Marko found the door unlocked but chained, and he was able to see the carnage inside. Police cars arrived and closed off intersections. Members of the Toronto Emergency Task Force lobbed tear gas into the apartment. Faces covered by gas masks, they stormed inside to discover five bodies in different rooms, all dead. The final gunshot had come from the bathroom, when Danylewycz put the barrel of his gun in his mouth and pulled the trigger.

Investigations by Toronto Police and American authorities soon revealed that Danylewycz was mentally ill and had received psychiatric treatment in Cincinnati. Described as clean-cut and a loner, Danylewycz had unexpectedly quit his job — working as an Easter Seals driver for handicapped persons — just days before coming to Toronto. Police soon found another handgun and notes in which the killer described how he would carry out the murders.

Several days after the murders, I attended the visitation at a funeral home in the city’s west end. All five oak caskets were closed, name cards atop each, and arranged in a semi-circle. When I shook Marko’s hand, I felt grief for another human being I had never felt before or have since. In time, Marko moved on, becoming a highly respected scholar and author.

There are few things more frightening than the thought of being in a comfortable, seemingly safe place — our living room or backyard, or a restaurant, movie theatre, church, or school — and having that serenity destroyed in moments by a madman armed with guns, knives, bombs, or other weapons. Tragically, mass murders and spree killings are becoming more common worldwide, and although police are able to piece together why someone chose to kill masses of innocent people, we are — despite the work of investigators, psychiatrists, and other experts — no closer to

preventing

these massacres from occurring. History is full of accounts of mass murderers, targeting groups based on race, gender, familial relationship, or any other reasons they justify in their delusional minds. As one fades from memory, he is replaced by another. Yesterday’s Charles Whitman — who stole fourteen lives while shooting from the tower at the University of Texas at Austin in August of 1966 — will be replaced by Norwegian mass murderer Anders Behring Breivik, who massacred seventy-seven in July of 2011, and James Holmes, who murdered twelve and wounded fifty-eight others during a premiere of the Batman movie

The Dark Knight Rises

in Colorado a year later.

Along with Whitman, Breivik, and Holmes, there have been many others who, feeling marginalized and fuelled by loathing, chose to kill. In December of 1989, twenty-five-year-old Marc Lépine slaughtered fourteen young women at Montreal’s École Polytechnique. Rather than address his own inadequacies as a man, Lépine blamed “feminists” for taking over non-traditional jobs. In a disturbing twist, a friend of mine, a female student at the École Polytechnique, had mercifully left twenty minutes before Lépine’s rampage.

As someone who has devoted a considerable amount of his life to writing about crime, I find nothing more terrifying than mass murderers and spree killers. Serial killers tend to target victims based on any number of factors, including gender, appearance, and race. Ted Bundy preferred brunette females, and John Wayne Gacy targeted young men. Mass murderers and spree killers think nothing of killing friends, family, and anyone else unfortunate enough to get in the way.

In

Rampage: Canadian Mass Murder and Spree Killing

, Lee Mellor has done an admirable job of bringing dozens of cases to light. Some, like the École Polytechnique massacre, are well known, while others have remained hidden — until now. Detailing not only the crimes committed, Mellor explores the twisted mindsets and motives behind these killings, and has created a work that will undoubtedly lead to a greater understanding of why these massacres occur, and what can be done to prevent tragedies in the future.

Preface

In my first work,

Cold North Killers

, I documented and analyzed the history of serial murder in Canada.

Rampage: Canadian Mass Murder and Spree Killing

continues in the footsteps of its predecessor, shifting focus to multiple murderers who are slightly more hot-blooded in nature. Unlike serial slayers, mass murderers and spree killers do not experience the cooling-off period that would allow them to retreat back into anonymity. Rather, like bombs, they explode upon society, either in a single act of abrupt devastation or a rapid chain of smaller eruptions. This is not to say that their crimes are spontaneous; in many cases, they have spent months or years planning and working themselves up psychologically to the big event. As we will see in the cases of

Thomas Easby

(Chapter 3) and

Albert Guay

(Chapter 12), when a mass murderer successfully eludes capture, he typically does not go on to kill again. However, the case of

Alexander Keith Jr.

(Chapter 3) indicates that there are exceptions to this rule (see also the serial killers Dennis Rader, Anatoly Onoprienko, and Nathaniel Code).

Contrary to the methods of serial killers, most rampage murderers do not take precautions to ensure their own freedom and survival. In fact, to borrow from T.S. Eliot’s “The Hollow Men,” many have opted to end their miserable lives with a bang rather than a whimper. Like

Denis Lortie

(Chapter 11) or

Marc Lépine

(Chapter 1), they may feel they are making a profound final “statement” directed at a world that has denied them their rightful place. They conclude that society has driven them to suicide, and rather than meekly ending their own lives, decide to take as many others with them as possible. After all, in their paradigm we are responsible for the misery of their existence. This is truer in some cases than others. The unfortunate tragedy of

Pierre Lebrun

(Chapter 10) reveals that bullying and cliquism may contribute significantly to a mass murderer’s psychological destabilization. Severe mental illness, in which the subject experiences a break from reality, is also more common in rampage killers than in serial offenders, as the cases of

Victor Hoffman

(Chapter 13) and

Swift Runner

(Chapter 2) illustrate.