Rasputin (19 page)

Authors: Frances Welch

It is clear that Yussoupov had wanted for some time to be the man ridding the Court of this troublesome peasant. However, at some stage in the proceedings, he began coveting a more central, and more glamorous role: as assassin.

The French Ambassador, Paleologue, was

disparaging

about Yussoupov’s motives for disposing of

Rasputin

: ‘Felix has regarded the murder of Rasputin mainly as a scenario worthy of his favourite author Oscar Wilde.’ In her memoir, Maria Rasputin also invoked Wilde with reference to Yussoupov, insisting that the Prince had been corrupted by his three years as an

undergraduate

at University College, Oxford. In the land of Oscar Wilde and ‘Bosie’, she wrote, he had fallen for ‘the more inviting college of Sodom’.

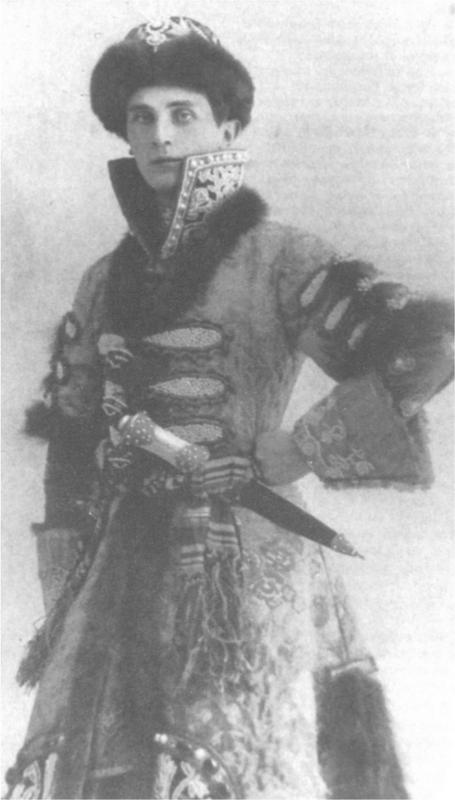

Prince Yussoupov had always relished being centre stage. As a toddler he would demand: ‘Isn’t Baby

pretty

?’ At 12 he dressed himself up as a girl, in a wig and his mother’s pearls, before singing at St Petersburg’s Aquarium club. He was rumbled only when one of his mother’s friends recognised the jewellery. His father was horrified, calling his son ‘a guttersnipe and a

scoundrel

’. The young Felix enjoyed knockabout japes, once

getting his dog drunk and allowing it to pee on guests. On another occasion he dressed it in wig, face paint and powder, before propelling it into the drawing room, where his mother was talking to a priest. Later, when travelling to England, he circumvented quarantine laws by dressing his bulldog as a baby.

Yussoupov never quite got over his prettiness. As an adult he was tall, clean shaven and still pretty; with neat features and a delicate mouth curled upwards at the corners in a cynical smirk.

He and Rasputin first met in 1909; the Prince had been unimpressed. The Man of God had, in turn,

dismissed

Yussoupov as a ‘frightened schoolboy’. As he said to his ever loyal Munia: ‘He needs help or the devil will gobble him up for dinner.’

But Munia was not to be influenced by either party against the other. She was a lifelong friend of the

Yussoupovs

, but she was also in the thrall of Rasputin for eight years. Her own relationship with Rasputin had been initiated through her passion for Yussoupov’s luckless older brother, Nikolai, who had been killed, aged just 26, in a duel. After his death, she had tried

desperately

to contact him through clairvoyants and had then resolved to lock herself away in a convent.

Rasputin

seemed to answer both these needs.

Seven years after their first meeting, Yussoupov was still critical of Rasputin. He thought Rasputin changed, his face more flabby and puffy. But his main

preoccupation

, throughout this second meeting, on November 20, was Rasputin’s disrespectful attitude towards Munia. They met at Munia’s house, and Yussoupov was

disgusted

when he saw Rasputin kissing his hostess on the lips. He wrote that he ached to crush Rasputin like an insect. When Munia invited him to sit down and take tea, he didn’t deign to answer, simply asking, as usual, whether he had received any phone calls.

Prince Youssoupov had always relished being centre stage. As a toddler he would demand: ‘Isn’t Baby pretty?’ At 12 he dressed himself up as a girl, in a wig and his mother’s pearls, before singing at St Petersburg’s Aquarium club.

At their first meeting, Yussoupov had kept his

distance

from Rasputin; now he had to make intimate overtures. He told Rasputin he wanted to be cured of his homosexuality, as it was affecting his marriage. Munia testified that he was also ‘complaining of chest pains’. Finally, the Prince said that his wife was in need of

treatment

for some mystery ailment and Rasputin pressed him for details. Throughout their discussion, the Man of God was full of good will, declaring: ‘There’s no trash with me.’

Munia cheerily insisted that Rasputin would love to hear Yussoupov play the guitar. Continuing in the vein of revelry, Rasputin asked Yussoupov to

accompany

him to the gypsies, as he would say: ‘With God in thought but with mankind in the flesh.’ But Yussoupov refused to commit himself, saying he had to prepare for his Military College exams. When Rasputin suggested Munia accompany him instead, her mother expressed her horror. Rasputin rounded on her: ‘What are you cackling about?’

He seemed preoccupied, as usual, by the phone. When it rang, he barked at Munia: ‘I expect that’s for me. Go and see.’ Having spoken on the phone, he

returned

, out of sorts. It emerged that he had been

discussing

the controversial Protopopov, probably with Anna Vyrubova. After several further calls, he appeared

to have won his case. As he told Munia later: ‘After I’d shouted a bit they calmed down…’

Yussoupov’s next meeting with Rasputin was at the flat in Gorokhovaya Street; he and Munia were dropped at a discreet distance away. Rasputin himself welcomed them at the door: ‘You’ve come at last. I’ve been waiting.’ Yussoupov disapproved of the flat décor, sniffily noting paintings badly executed and a general feel of ‘

bourgeois

wellbeing and prosperity’.

The two men were left alone after the Man of God snapped at Munia: ‘Go into the other room.’ By way of a conversational gambit, Rasputin sneered at the Duma, evidently forgetting his intention not to ‘uselessly offend’ members. He now dismissed them as ‘dogs collected to keep other dogs quiet’, adding over-optimistically that ‘their babblings won’t last much longer’. He boasted to Yussoupov: ‘Say the word and I’ll make you a minister,’ and unnerved him by taking his hand and saying: ‘Don’t be afraid of me.’

Both parties seemed to enjoy a certain

theatricality

. But how clear were they about their ever-changing roles? Rasputin, increasingly the fearful victim, was playing, once again, the mover and shaker at the heart of Government. Yussoupov, masquerading as the

tremulous

patient, was steeling himself to play murderer.

There was no doubt that Yussoupov, once the St Petersburg flâneur, had become an intriguer. He was confounding detractors with his new sense of purpose, not least the Tsar’s younger sister, Grand Duchess Olga, who in the past had spoken disparagingly of the: ‘utterly unpleasant impression he makes, idling at such times’.

After Yussoupov’s visit, Rasputin reverted to tragedy, writing plaintively to the Tsar: ‘I shall be killed. I am no longer among the living.’

The Tsarina was, as usual, immersed in her own scenario. On November 2 1916 she wrote: ‘Anxious about Baby’s arm so asked our Friend to think about it.’ On December 4, by which time Rasputin was in imminent danger, she told her husband to have ‘more patience and deepest faith in the prayers and help of our Friend’. And a few days later she urged him to ‘rely on

Rasputin

’s wonderful brain – ready to understand everything’.

P

rince Felix Yussoupov spent the snowy day of

December

16 adding finishing touches to an elaborate

mise en scène.

An empty wine cellar at his sumptuous palace on the Moika Canal had been converted into a dining room. The room was freshly painted and decorated: new curtains were hung, doors nailed in place and electric wiring installed. Lavish furniture was brought from other rooms, including carved wooden chairs, porcelain vases and a bearskin rug.

The table was laid as though a dinner had just taken place, with smeared plates, used cutlery and

scrunched-up

napkins. Drops of tea were poured into the teacups and half-eaten cupcakes strewn alongside place settings on the table at which, as Yussoupov pronounced

proudly

, ‘Rasputin was to have his last cup of tea’.

In the afternoon, Yussoupov took himself off

through the blizzard to the Kazan Cathedral, to pray for two hours. Convinced of the justice of his mission, he would have enjoyed an inspiring session, unaware that his victim had visited the cathedral days before. After attending to his spirit, Yussoupov visited the Military Academy; he intended to take his exam the following day.

He had three main fellow conspirators. Vladimir Purishkevich was the Duma member whose recent speech had so impressed Yussoupov. He was known for several idiosyncrasies, not least throwing water at his adversaries and cocking a snook at the Socialist

element

by sporting their symbolic red carnation in his fly buttons. It fell to Purishkevich to procure chains heavy enough to carry a body to the bottom of the Neva River. That fateful day he spent several nervous hours working at home, before venturing out to attend the Duma.

Purishkevich was 46, balding, with a full black beard and pince-nez. He had been immediately taken with what he saw as Yussoupov’s ‘indescribable elegance and breeding’ and was clearly enamoured of the romance of the murder plot. Later, describing the stage set of a cellar, he noted excitedly that it resembled an ‘elegant bonbonniere in the style of ancient Russian palaces’ and that ‘the pink and brown petits fours were chosen to complement the colour of the walls’.

The second conspirator was Grand Duke Dmitri, the Tsar’s cousin, who was aged just 25 and also

striking

, with large, plaintive, hooded eyes. Purishkevich

described

him as a ‘handsome, stately young man’.

And the third was Dr Stanislaus Lazovert, a friend

of Purishkevich: an army doctor, he had worked in a hospital train run by Purishkevich. Among Lazovert’s tasks was the preparation of one of Purishkevich’s

hospital

cars, to be used to transport the body to a hole in the ice next to the Petrovsky Bridge. Lazovert spent hours tinkering with the engine, though not very

fruitfully

as it turned out: during its brief mission, the car kept stalling. He painted over an identifying ‘semper idem’ (‘always the same’) emblem on its side.

Dr Lazovert’s primary role, however, was to provide the cyanide, which he cut up and sprinkled into wine glasses and cupcakes. He created a setback during the preparations when he threw his rubber gloves into the fire, filling the room with smoke. He later passed out and had to be revived in the snow. But at this early stage of the proceedings, he readily prepared himself for the role of chauffeur. By 11.00pm he had dressed up in a suitable coat and peaked cap. He collected Purishkevich and the pair arrived at Yussoupov’s splendid Moika Palace at the same time as Grand Duke Dmitri.