Real Food (8 page)

Authors: Nina Planck

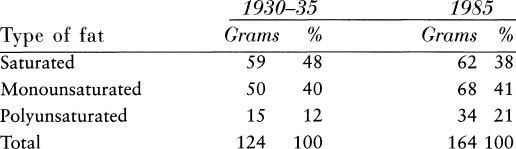

As the table shows, from 1935 to 1985, the percentage of saturated fats in the American diet

fell,

while consumption of polyunsaturated vegetable oils more than doubled. (Note, too, that we ate more total fat in 1985, possibly

due to larger portions. Not only did the low-fat campaign fail to reduce obesity and heart disease; it simply

failed.)

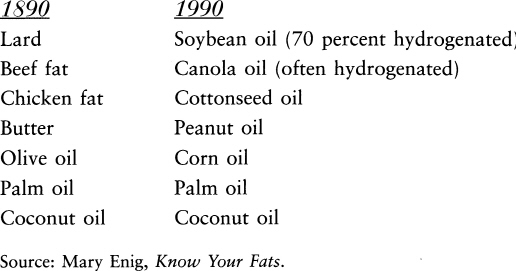

The changing face of the most popular fats in the diet tells the same story in a different way. In 1890, the main fats we

ate were the traditional farm fats: butter, lard, and chicken and beef fat. A hundred years later, the top three fats were

polyunsaturated vegetable oils such as soybean and canola oil, rarely found in traditional human diets.

DAILY FAT INTAKE BY TYPE OF FAT, 1930-85

The most dramatic change in the American diet is the increase in polyunsaturated fats, up by 127 percent. The percentage of

saturated fats

fell.

Many of the polyunsaturated fats shown are hydrogenated vegetable oils, which raise LDL and reduce HDL.

FATS IN THE U.S. FOOD SUPPLY (IN DESCENDING ORDER OF MARKET SHARE)

Note that all the nineteenth-century fats are unrefined with a long history in the human diet. The top three oils in 1990

were unknown in traditional diets.

With this record of fat consumption— fewer saturated fats, more polyunsaturated vegetable oils— proponents of the cholesterol

theory would

not

have predicted this: by the 1950s, heart disease was the leading cause of death in the United States. It's a striking fact,

worth restating in another way: as consumption of saturated fats

fell

in the first half of the twentieth century, heart disease

rose.

This suggests that something other than butter and other traditional saturated fats is to blame for unhealthy cholesterol

and heart disease.

That something is the trans fat in hydrogenated vegetable oils like margarine. As the world now knows, trans fats lower HDL

and raise LDL, among other things. Real dairy foods, it appears, are innocent. Back in 1991— when heart doctors were touting

vegetable oil spreads—

Nutrition Week

reported that men eating butter ran half the risk of developing heart disease as those eating margarine.

13

.

Recent studies cast doubt on the link between dairy foods, high cholesterol, and heart disease. Consider the Finns, who have

the highest cholesterol in the world. "According to the [cholesterol theory], this is due to high-fat Finnish food," writes

Dr. Uffe Ravnskov, author of

The Cholesterol Myths

and a leading researcher in a group known as the Cholesterol Skeptics. "The answer is not that simple." Within Finland, cholesterol

levels vary greatly. In one study, Finns who ate twice as much margarine and half as much butter as other Finns had the

highest

cholesterol. Those with the highest cholesterol also preferred skim milk to whole milk.

14

WHY I DON'T DRINK SKIM MILK

Let me count the ways. The first reason I don't drink skim milk is flavor— it's in the fat. Second, butterfat helps the body

digest the protein, and bones require saturated fats in particular to lay down calcium. Third, the cream contains the vital

fat-soluble vitamins A and D. Without vitamin D, less than 10 percent of dietary calcium is absorbed.

15

In the American diet, whole milk was the traditional source of vitamins A and D and calcium. Skim milk— especially industrial

skim— is an inferior source of both. Skim and 2 percent milk must, by law, be fortified with synthetic vitamin A and synthetic

vitamin D3. There is some evidence that both synthetic vitamins are toxic in excess. Finally, whole milk contains glycosphingolipids,

fats that protect against gastrointestinal infection. Children who drink skim milk have diarrhea at rates three to five times

higher than children who drink whole milk.

16

In 2005, researchers reported on a twenty-year study of Welsh men. The high milk drinkers had a lower risk of heart disease

than those who drank the least, even though cholesterol and blood pressure were similar in high and low milk drinkers. "The

present perception of milk as harmful in increasing cardiovascular risk should be challenged," wrote the authors, "and every

effort should be made to restore [milk] to its rightful place in a healthy diet."

17

As researchers demonstrate every day, many other factors— sugar, lack of B vitamins, too many refined vegetable oils, lack

of exercise, smoking— are at work in heart disease. But these anomalies about milk and butter— facts that don't fit the orthodox

theory— cry out for explanation.

Meanwhile, I should mention that some studies

have

linked milk consumption and high cholesterol. What could account for that? According to Dr. Kilmer McCully, a student of cholesterol

metabolism and the author of

The Heart Revolution,

industrial powdered milk is one culprit. Dried milk powder is created by a process called spray-drying, which creates oxidized

or damaged cholesterol. Researchers in 1991 wrote, "Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is more atherogenic than native

[unoxidized] LDL."

18

In other words, oxidized LDL causes atherosclerosis.

Milk powder containing oxidized cholesterol is a common ingredient in industrial processed foods including milk, yogurt, low-fat

cheese, cheese substitutes, infant formula, baked goods, cocoa mixes, and candy bars. Nonfat dried milk is also added to industrial

skim and 2 percent milk. In fact, skim milk may be made

entirely

of dried milk powder mixed with water. Unfortunately, the label is misleading. It will simply say "skim milk," not "skim milk

powder." The better dairies don't use powdered milk; they make skim milk from whole fresh milk simply by skimming off the

cream.

My conclusion that traditional milk is a good thing is not original. In the 1930s and '40s, Dr. Francis Pottenger ran tuberculosis

clinics where he treated patients with raw milk from grass-fed cows. A professor at the University of Southern California

and president of the American Academy of Applied Nutrition, he published dozens of peer-reviewed articles and founded a hospital

for the treatment of asthma. In his day, experts were already blaming milk for high cholesterol, but Pottenger believed traditional

milk was falsely accused. In his now classic studies on raw and pasteurized milk,

Pottenger's Cats,

the doctor wrote: "The charge that milk produces high cholesterol in humans is largely based on the premise that the ingestion

of cholesterol and the deposit of cholesterol are the same. Extensive use of quality raw milk, cream, and farm eggs with tuberculosis

patients failed to produce a single case of hypercholesterolemia [high blood cholesterol] and atheroma [plaque]. A life-time

consumption of clean, fresh raw milk from healthy cattle does not produce metabolic diseases. Cholesterol is not the villain;

the villain is what man does to his cattle and milk."

I like the way Pottenger put that. As I sorted through the facts about milk and health, it was helpful to keep asking:

which

milk?

Many things aren't what they used to be, and milk is one of them.

Traditional and Industrial Milk Are Different

ONE OF MY FAVORITE children's books is Maj Lindman's

Snipp,

Snapp, Snurr, and the Buttered Bread,

about Swedish triplets who are hungry for bread and butter. Alas, there is no butter. They go to the family cow, Blossom,

who "stood munching her dry hay and looking very sad." When the boys ask nicely for milk with "plenty of cream" so their mother

can make butter, Blossom shakes her head sadly; she has none to give. "I know what she needs," says one boy. "Fresh green

grass." When spring comes and the pasture turns "green and juicy," they give Blossom a basket of fresh grass. Delighted, she

gives back rich cream, and the equally delighted boys have butter for their bread.

First published in the United States in 1934,

The Buttered

Bread

is a sweet story, but it's more than that. It nicely illustrates the point— once well known to farmers in Sweden, America,

and all over the world— that cows produce the most cream and the best butter when eating lush green pasture, particularly

the fast-growing grass of spring and fall. In the Swiss dairy villages Weston Price visited, spring butter was so highly prized

it was blessed by priests and used in religious ceremonies. Spring butter from grass-fed cows has been tested in the lab (by

Price and others) and found to be superior. Blossom's story is poignant because so few cows today eat fresh grass.

Modern industrial milk and the milk we drank ten thousand years ago— even the milk most Americans (including Great-Aunt Esther

in Milford, Illinois) drank fifty years ago— are different. Traditional milk comes from cows fed mostly on fresh grass and

hay; it is raw and unhomogenized. Industrial milk comes from cows raised indoors and fed mostly on a corn, grain, and soybean

ration, typically with a dose of synthetic hormones to boost milk production. Industrial milk is then pasteurized and homogenized.

Real milk is healthier than the industrial kind, and its superior flavor is unmistakable.

Because cows eat grass, traditional milk is seasonal. Ancient shepherds moved animals frequently to fresh pasture for the

best grazing. In the winter, the traditional cow was " dry"— pregnant and not producing milk— and in the spring she gave birth

to a calf and began giving milk again. Traditional dairy foods naturally reflect this seasonal pattern. In the spring, when

fresh pasture for grazing was plentiful, early shepherds had fresh milk, yogurt, and young cheeses. In the winter, when the

cows were dry, they ate aged cheeses made the previous summer and fall. The best dairy farmers still raise cows, goats, and

sheep on grass— they are known as

grass

farmers

— and the better cheese shops offer seasonal cheeses made from the milk of grass-fed animals.

Compared to industrial milk, dairy foods from grass-fed cows contain more omega-3 fats, more vitamin A, and more beta-carotene

and other antioxidants. Butter and cream from grass-fed cows are a rare source of the unique and beneficial fat CLA. According

to the

Journal of Dairy Science,

the CLA in grass-fed butterfat is 500 percent greater than the butterfat of cows eating a typical dairy ration, which usually

contains grain, corn silage, and soybeans.

19

A polyunsaturated omega-6 fat, CLA prevents heart disease (probably by reducing atherosclerosis), fights cancer, and builds

lean muscle. CLA aids weight loss in several ways: by decreasing the amount of fat stored after eating, increasing the rate

at which fat cells are broken down, and reducing the number of fat cells. Most studies of CLA and cancer have been conducted

on animals, and more research is needed, but findings are encouraging. CLA inhibits growth of human breast cancer cells in

vitro. A Finnish team found that women eating dairy from pastured animals had a lower risk of breast cancer than those eating

industrial dairy.

20

The dairy industry is well aware of the commercial opportunity presented by the words

cancer fighting

or

aids weight

loss

on milk cartons, and scientists are working on ways to increase CLA in milk without going to the trouble of putting cows on

grass. In 2003, the

Journal of Dairy Science

reported that feeding fish oil and sunflower seeds (containing linoleic acid, which cows convert to CLA) raises CLA in milk.

There are CLA-fortified milk products in the works, but problems with taste and texture linger. "The addition of CLA to milk

decreased overall acceptability, overall flavor, and freshness perception of milk," reported one study coolly.

21

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, these "functional foods" or "nutraceuticals," as the industry calls them,

pay a high compliment to traditional foods.

Traditional milk is free of synthetic growth hormones. Most industrial milk comes from cows treated with a genetically engineered

bovine growth hormone called rBGH (or rBST) to boost milk production. Industrial cows are milked three times a day. Unfortunately

for the cow, the hyperproduction stimulated by rBGH increases her risk of mastitis (udder infections) and shortens her life

dramatically, from about ten years to five.