Red Army (15 page)

The view from the air filled Trimenko with a sense of his personal power. The army commander was not given to self-indulgent emotions; his life had been spent in a struggle to master the weaknesses of individual temperament, but the sight through the rain-speckled windows of the helicopter excited him with a pleasant awe. These were

his

endless columns of combat vehicles and support units,

his

tens of dozens of deployed artillery batteries, with the rearmost hurrying to move, others locked in close column on the roads, and still more executing fire missions against the stone-colored horizon.

His

air-defense systems lurked on hilltops like great metal cats, radar ears twitching and spinning. Trimenko’s pilot flew the road trace, staying low, unwilling to trust the protection of the big red star on the fuselage of the aircraft. But the army commander had transcended such petty worries in the greatness of the moment. He felt consumed by the growling enormity of men and machines flowing to the west like a steel torrent, absorbed into a being greater than the self.

In detail, it was a far-from-perfect vision. Some columns were at a standstill. Here and there, crossroads teemed with such confusion that Trimenko could almost hear the curses and arguments. Soviet hulks had been shoved off the roadways where the enemy’s air power or long-range artillery fires had caught them. Incredible panoramas opened up, then closed again beneath the speeding helicopter.

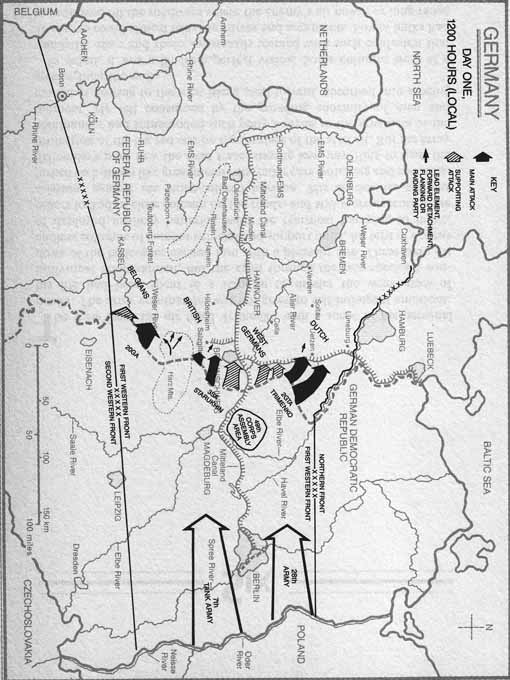

Trimenko realized that, to those on the ground, waiting nervously for a column to move or for an order to come, the war probably seemed like a colossal mess on the edge of disaster. But from the sky, from the god’s-eye view, the columns moved well enough. For every march serial that had bogged down, two or three others rushed along parallel routes. And the flow carried them all in the right general direction. Trimenko knew that one division already had pushed its lead elements across the canal a bit to the north, even as a major assault crossing operation was being conducted in another divisional sector. Some units had penetrated to a depth in excess of thirty kilometers from their start lines, and one reconnaissance patrol had reported in from a location fifty-two kilometers west of the border. Meanwhile, the enemy’s power to strike out to halt the flow of Soviet forces had proven surprisingly weak. Trimenko had already heard the fearful casualty reports from the morning’s engagements. Kept in perspective, the numbers were acceptable -- and he had no doubt that they were somewhat exaggerated in the heat of combat and in the process of hastily relaying data up the echelons. The prospect of inaccurate data for his forecasting calculations troubled Trimenko more than did the thought of the casualties themselves.

Jet aircraft, invisible in the haze, passed nearby, and the sound slammed into the helicopter. Trimenko thought that Malinsky had been absolutely correct to support the air offensive so heavily. With the low number and limited range of the surface-to-surface missiles available to the enemy now, air power had been the great enemy threat. In his private, less-assured moments, Trimenko had worried that NATO would catch them right at the border-crossing sites, where the engineers had opened gaps in the frontier barriers. But the threat had not materialized. NATO’s ground attacks with aircraft were deadly, but haphazard, and Trimenko suspected that many of NATO’s aircraft had, indeed, been caught on the ground. Starukhin had been an ass to press the issue of initial close air support with Malinsky, and the present obviousness of it pleased Trimenko. Starukhin, he mused, was the sort of Russian officer he himself most despised, and a type still far too common -- the man who raged and stamped and shouted to announce his own power and grandeur, to convince a skeptical world of how much he mattered. Trimenko, no less concerned with his own importance, found tantrums inefficient and primitive. He believed that the times called for a more sophisticated approach to the exploitation of resources, whether material or human.

Trimenko stared out over his army as it marched deeper into West Germany. The spectacle offered nothing but confusion to the man with a narrow, low-level perspective, he realized, but it revealed its hidden power, incredible power in an irresistible flood, to the man who could look down.

“Afterburners now.”

“Fifty-eight, I’m still in the capture zone. I’m hot.”

“Open it up, Fifty-nine. Flares away. Get out of the kitchen.”

“He’s on me.

He’s on me.”

“Turning now.

Go.”

The junior pilot in the wing aircraft fired his flares and banked, engines flushing a burst of power.

“More angle, little brother.

Pull it around.”

Pilot First Class Captain Sobelev watched as an enemy air-defense missile miraculously passed beside his wingman’s aircraft and carried about five hundred feet before exploding. Sobelev felt his own aircraft buck like a wild horse at the blast.

“Steady now. Keep her steady, Fifty-nine.”

The planes had come out two and two, but the trailing pair had been shot down before they even reached the Weser River. Now, deep in the enemy’s rear, the air defenses had thinned. But it was still nightmarish flying. It was not at all like Afghanistan. Flying in and out of Kabul and good old Bagram had been bad enough. With the eternal haze over Kabul, filthy dust on the hot wind, and later the horribly accurate American Stinger missiles. But all of that had been child’s play compared to this.

“Fifty-eight, my artificial horizon’s out.”

Shit, Sobelev thought. “Just stay with me,” he answered. “We’re going to do just fine.”

Sobelev sympathized with the lieutenant’s nervousness. It was their second combat mission of the day, and today was the lieutenant’s first taste of war. If Afghanistan had been this bad, Sobelev thought, I might have quit flying.

“Stay with me, little brother. Talk to me.”

“I’m with you, Fifty-eight.”

“Good boy. Target heading, thirty degrees.”

“Roger.”

“Keep those wings level now . . . final reference point in sight ... go to attack altitude . . .

talk

to me, Fifty-nine.”

“I have the reference point.”

“Executing version one.”

“Correcting to follow your approach.”

“On the combat course . . .

now . . .

hold on, it’s going to be hot.”

“Roger.”

“Target . . . ten kilometers . . . steady ... I have visual.”

Sobelev saw the airfield coming up at them like a table spread for dinner. Enemy aircraft continued to land and take off.

“Hit the apron. I’ve got the main runway.”

“Roger.”

Air-defense artillery suddenly came to life in their path, drilling the sky with points of light.

“Let’s do this clean . . . hold it ...

hold straight . . straighten your wings.”

In Afghanistan, you flew high and tossed outdated ordnance at the

kishlaks

with their mud buildings that had not changed for a thousand years. The bombs changed them in an instant.

Sobelev was determined to bring his wingman out. Wingboy, he thought, children at war, already forgetting how young he had been on his first tour of duty in Afghanistan.

Sobelev led them right into the general flight paths of the NATO aircraft taking off, making it impossible for the air-defense guns to follow them.

“Now.”

The lieutenant shouted into the radio in childish elation. The two planes lifted away from the enemy airfield, and, as they banked, Sobelev caught a glimpse of the heavy damage that already had been dealt to the base by previous sorties. Black burned patches and craters on the hardstand. Smoking ruins in the support area. Emergency vehicles raced through corridors of fire. Sobelev heard his flight’s payload detonate, adding to the destruction.

“Let’s go home, little brother . . . heading . . . one ... six ... five.”

An enemy plane suddenly shot straight up in front of Sobelev. He recognized a NATO F-16. As the plane twisted into the sky, disappearing from view in the grayness, Sobelev’s mouth opened behind his face mask. He had never seen a plane ... a pilot . . . maneuver like that. It shocked him.

After a long, long few seconds, he spoke. “Hostiles, Fifty-nine ... do what I do ... do

exactly

what I do ... do you understand?”

“Roger.” But the exuberance was gone from the lieutenant’s voice. He, too, had seen the enemy fighter’s acrobatic climb. Now they both wondered where the enemy aircraft had gone. Sobelev looked at his radar screen. It was a mess. Busy sky.

“Follow me

now,

Fifty-nine,” Sobelev commanded. And hope I know what I’m doing.

Major Astanbegyan leaned over the operator’s shoulder, watching the scanning line circle the radar display.

“Does

anyone

respond to query?” the major asked.

“Comrade Major,” the specialist sergeant said, with weary exasperation in his voice, “I register responses. But it’s all so cluttered that they intermingle before I can sort targets. Then the jamming starts again.”

Astanbegyan told the boy to keep on trying. He was beginning to feel like a unit political officer in his struggle to maintain a positive collective outlook in the control staff. He had begun the morning by shouting when things went wrong, but he had soon shouted himself out. There were so many unanticipated problems that he quickly realized he was only making the work harder. Now he simply did what he could to keep the entire air-defense sector from collapsing into anarchy.

He turned away from the boy at the console. He knew the sergeant was trying, that he sincerely wanted to do what was right. The officers manning scopes and target allocation systems were doing no better. The NATO aircraft were using the same penetration corridor in sector as those of the Warsaw Pact, and it was a hopeless muddle. Out on the ground, the batteries were operating primarily on visual identification.

The battle management computers were a disappointment as well. So far, they were handling systems location and logistics data fairly well -- or seemed to be, since there was no way of knowing how accurate all of the inputs and outputs were at this point. But the sorting and assigning of targets was going badly. Astanbegyan had no doubt that aircraft were being knocked out of the sky. He had over a dozen reported kills. But he was less certain about who was being shot down.

“Comrade Major,” a communications specialist called to him. “The commander of Number Five Battery wishes to report.”

“Take his report, then.”

“He wishes to report to you personally, Comrade Major.”

Astanbegyan stepped over to the communications area and took the receiver from the specialist.

“Six-Four-Zero. Go ahead.”

“This is Six-Four-Five. I have two systems down. Enemy air-to-surface missiles, anti-radiation, I think. We got the bastard, though.”

“All right,” Astanbegyan said, although he was far from happy with the news. What could you do, order your subordinates to go back and start from the beginning and not lose the systems next time? “How are you receiving your encoded instructions?”

There was a momentary silence on the other end.

“This is Six-Four-Five,” the voice returned. “I haven’t received any for the last hour.”

Astanbegyan felt his self-control drain away. “Damn it, man, this isn’t an exercise. We’ve been sending constantly. Check your battery console.”

“Checking it now.”

“And next time don’t wait until you have to call me and tell me you’ve lost the rest of your battery.”

“Understood.” But the voice shook. “Listen, Comrade Major . . . we’re running low on missiles.”

“You can’t possibly have fired everything on your transporters.”

“Comrade Maj -- I mean, Six-Four-Zero, I haven’t seen the trucks all day. The technical services officer became separated from the unit. You wouldn’t believe what the roads are like out here.”

“You find those damned trucks.

If you have to walk to Poland. Better yet --

you

walk

forward.

Send somebody else to the rear. What the hell good are you without missiles? You ought to be court-martialed.”

“You don’t know what it’s like out here.”

“Comrade Major,”

a radar-tracking specialist shouted, interrupting. “Multiple hostiles, subsector seven, moving to four.”

Immediately, the shriek of jets flying low penetrated the walls of the van complex, shaking the maps and charts on the walls, and drawing loud curses from electronics operators whose equipment flickered or failed.

“Where did they come from?” Astanbegyan screamed, giving up his last attempt at composure.

“They were ours, Comrade Major.”

Astanbegyan ran his hand back over his scalp, soothing himself. A good thing, too, he thought.

Colonel Tkachenko, the Second Guards Tank Army’s chief of engineers, watched the assault crossing operation from the lead regiment’s combat observation post. Intermittently, he could see as far as the canal line through the periscope. He had studied this canal for a long time, and he knew it well. There were sectors where it was elevated above the landscape, with tunnels passing beneath it, and other sectors, like this one, where the waterway was only a flat, dull trace along the valley floor. This sector had been carefully chosen, partly because of its suitability for an assault crossing, but largely because it was a point at which the enemy would not expect a major crossing effort, since the connectivity to the high-speed roads was marginal. Surprise was the most important single factor in such an operation, and the local trails and farm roads would be good enough to allow them to punch out and roll up the enemy. Then there would be better sites, with better connectivity, at a much lower cost. Tkachenko refocused the optics, looking at the sole bridge where it lay broken-backed in the water. A few hundred meters beyond, the smokescreen blotted out the horizon. Under its cover, the air assault troops had gone in by helicopter to secure the far bank, and now the assault engineers on the near bank appeared as tiny toys rushing forward with their rafts and demolitions. Beyond the smoke-cordoned arena, the fires of dozens of batteries of artillery blocked the far approaches to any enemy reserves.