Red Mutiny

Authors: Neal Bascomb

Neal Bascomb

Eleven Fateful Days on the

Battleship

Potemkin

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

Boston ⢠New York

2007

Copyright © 2007 by Neal Bascomb

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections

from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Visit our Web site:

www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bascomb, Neal.

Red mutiny : eleven fateful days on the battleship

Potemkin /

Neal Bascomb.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN

-13: 978-0-618-59206-7

ISBN

-10: 0-618-59206-7

1. Bronenosets "Potemkin." 2. RussiaâHistoryâRevolution,

1905â1907. I. Title. II. Tide: Eleven fateful days on the battleship

Potemkin.

III. Tide: 11 fateful days on the battleship

Potemkin.

DK

264.

B

37 2007

947.08'3âdc22 2006030210

Book design by Melissa Lotfy

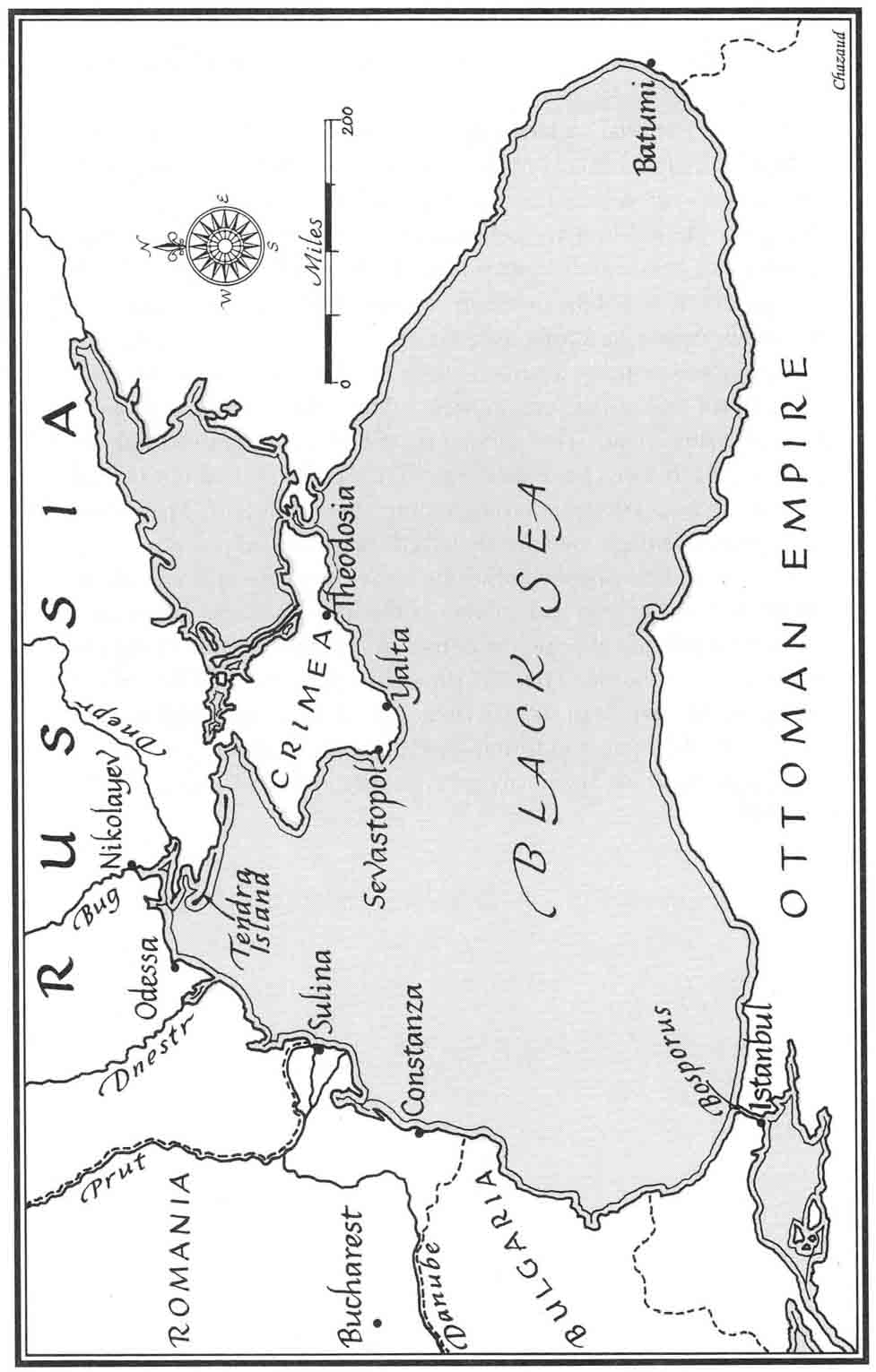

Map by Jacques Chazaud

Printed in the United States of America

MP

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ContentsFor My Grandparents,

LESTER AND BETTY LINCK

SUMPTER AND HELEN BASCOMB

AUTHOR'S NOTE

â¢

[>]

PROLOGUE

â¢

[>]

PART I

â¢

[>]

PART II

â¢

[>]

PART III

â¢

[>]

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

â¢

[>]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

â¢

[>]

RESEARCH NOTES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

â¢

[>]

NOTES

â¢

[>]

INDEX

â¢

[>]

Mutiny is a high military crime andâalongside treasonâthe gravest of crimes against the state. Its perpetrators risk court-martial and almost certain death. Rarely, however, is the act important in the sweep of history. The isolated bands of sailors or soldiers who rebel against their officers seldom warrant a place in a country's, let alone the world's, collective memory. Then there is the mutiny on the battleship

Potemkin.

In June 1905 on the Black Sea, the crew aboard the

Potemkin

killed their captain and took control of the most powerful battleship in the Russian fleet. The insurrection had begun over a protest against maggot-infested meat, but stale borsht was little more than a pretext for mutiny, an action planned months in advance by sailors turned revolutionaries. All of Russia was on the verge of insurrection against the despotic rule of Tsar Nicholas II, and these sailors hoped to bring the battleship to the people's side, leading to the tsar's fall from the throne.

Flying the red flag of revolution, the

Potemkin

ruled the Black Sea for eleven days. Hunted by battleship squadrons and individual destroyers from port to port, the sailors incited revolts on land, inspired other crews to mutiny, battled on land and sea, and revealed the rotting foundations of the Russian Empire. The sailors also captured international attention, dominating front-page news for weeks and compelling other heads of state to urge the tsar to resolve the situation before it upset the world's fragile balance of power. Pressured from within Russia and abroad to accept peace with Japan and agree to reforms that violated his sacred oath to uphold the autocracy, the tsar found

Potemkin

weighing heavily on his thoughts. Given telegrams from his naval commanders that "the sea is in the hands of mutineers" and reports that wholesale revolution might soon follow, his concern was understandable.

Remarkable events, as evidenced in the famous Russian film

Battleship Potemkin

created by director Sergei Eisenstein in 1925, not to mention the scores of books written about the mutiny by participants and by Russian scholars. However, all of these sources, to one degree or another, were influenced by politics, particularly politics after the Bolshevik Revolution. Over a century has passed since that first shot aboard the

Potemkin

sparked the uprising, and its story deserves to be freed of the myth and bias that have clouded it for so long. I have endeavored to tell this history through the eyes of the

Potemkin

sailors, hoping to reveal who they were, what drove them to dare mutiny, how they succeeded in surviving for eleven days while Russia and the world turned against them, and what ultimately brought their journey to an end. Furthermore, to draw a complete picture, I have woven in the views of the crews on other ships within the fleet, the naval officers who tried to suppress the uprising, the generals facing unrest throughout the region, Tsar Nicholas himself, and others.

It is clear now in hindsight that the events of 1905, including the

Potemkin

mutiny, served only as a "dress rehearsal" for the revolution that would eventually sweep the tsar from power. Twelve years and the misery of a world war would pass before these changes transpired. We also know that any chance for a more democratic government to replace the tsar's regime ended when the Bolsheviks seized the reins in October 1917, much as we are familiar with the terror and suffering that Lenin and his successors would inflict on the Russian people in an attempt to realize their political theories. Inevitably, these facts, as well as volumes of propaganda, color our perception of these sailors, their ambitions, and their chances of achieving some kind of victory.

The truth is, the

Potemkin

sailors were not struggling to advance some stage of history set forth in political philosophy; rather, they were acting against a ruinous autocratic regime that viewed them solely as vassals of the state, existing only to serveâand suffer, as was most often the case. The mutiny showed the willingness of some to face great odds and near-certain death to end oppression. Like those who stormed the Bastille against Louis XVI's reign or fought against King George III in the American colonies, the

Potemkin'

s leaders were ordinary, flesh-and-blood individuals at the forefront of a battle to win personal liberty and a voice in how their daily lives and their country would be led. Alone on the Black Sea, uncertain whether anyone would join them in their fight but sure the tsar of Russia would leverage all of his considerable powers to crush them, the sailors dared revolution. They acted while others stood by to judge and attempt to use the sailors' efforts for their own ends.

History does nothing, possesses no enormous wealth, fights no battles. It is rather man, the real, living man, who does everything, possesses, fights. It is not "History," as if she were a person apart, who uses men as means to work out her purposes, but history itself is nothing but the activity of men pursuing their purposes.

â

KARL MARX

A

T

91

RUE DE CAROUGE

in the city of Geneva, in a tiny apartment stacked with dusty magazines and books, with packing cases for chairs, two men spoke of revolution. It was the end of July, the year was 1905, and the focus of their conversation was Russia.

The two had only just met. The first, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, lived in the apartment with his wife. He went by the pen name Lenin. When he spoke of his rivals, the Mensheviks, his dark eyes hardened, he jabbed his fingers through the buttonholes of his vest, and then he drew back as if he was gathering venom before a strike. Although the Russian secret police, Okhrana, tracked his movements, considering him an enemy of the state, Lenin was largely an unknown figure outside socialist circles. One day he would lord over Russia, but his deeds as ofjuly 1905 were limited, and he acted more as a journalist than a revolutionary leader.

Okhrana agents in Geneva were also watching his guest that afternoon, but his deeds and name were known throughout the world. Hero to some, treasonous villain to others, Afanasy Nikolayevich Matyushenko was the leader of the mutiny on the battleship

Potemkin,

a rebellion that had occurred only a month earlier and had made Tsar Nicholas II question his very hold on power. Lenin, who was as stunned at its outbreak as anyone else, had already written that the eleven-day Black Sea mutiny, led by Matyushenko, marked the first important step of the Russian Revolution. "The Rubicon has been crossed," he declared in the socialist journal

Proletary.

To many, stories of Matyushenko summoned up a picture of a titan, but the twenty-six-year-old sailor sitting across from Lenin looked far from such. Short in frame, he had a lean, muscular face, pronounced Slavic cheekbones, and a slight upturn on the right side of his mouth, giving him the expression of someone in on a secret. His eyes, which many of his closest comrades knew could darken into a horrible rage, were largely hidden underneath thick red eyebrows. But it was not his appearance, nor his background as a peasant from a small Ukrainian village, that made him a giant; it was his presence. Men instinctively looked to him for direction. He was intelligent, a gifted speaker, and recklessly brave. Perhaps most important of all, people recognized, as one of his comrades said, that "he lived not for himself, but for others."

After the mutiny's end, Matyushenko had escaped the Black Sea shores for Bucharest, where he stayed with Professor Zik Arbore-Ralli, a Russian émigré who was once close to revolutionaries Mikhail Bakunin and Sergei Nechayev. Okhrana agents in Romania kept Matyushenko under the strictest surveillance, but they were forbidden to seize him on foreign soil. Worried these Russian agents might act precipitately, Arbore-Ralli and several

Potemkin

sailors pooled their money to send him to Switzerland to join the community of Russian revolutionary leaders in exile there.

Traveling with a fake Bulgarian passport, Matyushenko arrived by train in Geneva in early July. He sought financial support for his former crewmates and guidance on where he should next take his struggle against the tsar. The Russian secret police soon picked up his trail in Geneva after he met with several individuals on their watch list. Again, they could do nothing but watch. While in Switzerland, he became close with Father Georgy Gapon, the champion of St. Petersburg workers who had marched on the Winter Palace at the first of the year, but Matyushenko could barely stand any of the other revolutionary figures he met. Each party head attempted to recruit him. In the most direct terms, Matyushenko refused them all. "It's not for me," he told

one party's terrorist wing. "I'm a man of the crowd. Do what you like, I just can't do it."

These intellectual leaders of the revolution professed their love and respect for Matyushenko, but he knew they thought him nothing more than an ignorant sailor who could be taught to dance for their cause. One party chided him for not reading enough Karl Marx. Another proposed he concentrate more on August Bebel. Thinking for oneself was apparently out of the question in Geneva, Matyushenko reflected. He despised their bickering over theory. While they elbowed one another over whose party deserved credit for the

Potemkin

mutiny, sailors who had risked their lives alongside Matyushenko were days away from the firing squad. The starving people of Russia seemed only an afterthought to these revolutionaries. They certainly had not earned the right to even comment on the mutinyâgood or bad. The sailors had acted while these men merely talked and scribbled polemics.

In Lenin, Matyushenko found the most combative and vitriolic of infighters, the one who had splintered the Russian Social Democrats and issued polemic after polemic from his apartment concerning the true path to revolution. That afternoon, Matyushenko told him of the

Potemkin.

He had lost several close comrades in the mutiny, and the feelings of despair and triumph were still raw in the telling.

This story, theirs, begins in St. Petersburg in the cold heart of winter, 1905.

1Where there is a lot of water, there

you may expect disaster.âRussian proverb

Shine out in all your beauty,

City of Peter, and stand

Unshakable as Russia herself

And may the untamed elements

Make their peace with you.â

ALEKSANDR PUSHKIN,

The Bronze Horseman

T

HE NEVA RIVER

cut through the center of St. Petersburg, a mighty artery of ice. On its surface flowed a temporary electric tramway as well as horse-drawn sleighs. The sleigh drivers, bound in sheepskin, their beards white with icicles from their breath, followed paths outlined with pine branches. Police patrols scanned the river for thin spots, marking these with red flags, but in most areas, the ice was now thick enough for workers to cut out piano-sized blocks that would be stored for the hot summer months. Skating rinks dotted the river, enjoyed by those fortunate enough to have leisure time. Below the frozen surface, the water surged inexorably toward the Gulf of Finland, but that was a distant thought to the people of St. Petersburg who had gathered on the Neva and its banks to celebrate the Blessing of the Waters. It was January 6, 1905.